This article is published as part of Brazilian Black Awareness Month, celebrated every November around Black Consciousness Day on November 20. For the original article by William Reis, executive coordinator of AfroReggae, in Veja Rio, click here.

This article is published as part of Brazilian Black Awareness Month, celebrated every November around Black Consciousness Day on November 20. For the original article by William Reis, executive coordinator of AfroReggae, in Veja Rio, click here.

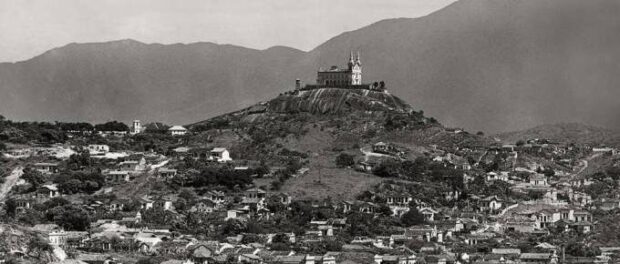

Vila Cruzeiro is situated in the Complexo da Penha group of favelas in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone and is known either for violence or for being home to former soccer player Adriano Imperador (Adriano the Emperor), who even today maintains a relationship with the community. Little is said about the rich history of this place. At the end of the 19th century, an abolitionist and republican priest ceded the space to formerly enslaved men who organized themselves in a quilombo (a refuge for escaped slaves and their descendants). Their resistance is present today in the traditions of the favela.

The Quilombo da Penha emerged after the 1888 abolition of slavery in the area surrounding the Our Lady of Penha Church. This marks a difference between Vila Cruzeiro and the majority favelas in Rio, which expanded in the 1960s and 1970s as a consequence of population growth.

Quilombo lands were always characterized by fertility, reservoirs, springs that originate on the edge of quarries, freshwater fish, and wild animals, essential ingredients to attract their residents. Even today, in my mother’s house, we have a freshwater spring that was and is still in use. With the end of the quilombo came population growth and several infill processes, and Vila Cruzeiro’s natural wealth began to disappear.

Transformed into a favela, Vila Cruzeiro kept its quilombo heritage alive through samba, funk, capoeira, and in the black aesthetic reproduced in beauty salons, soccer, and activism. While researching for this article, I sought out emblematic local figures, who have transformed Vila Cruzeiro into one of the most well-known favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Violence, which made Vila Cruzeiro famous, is present in the names of its alleys. The so-called Neighborhood 13 is a reference to the French film Banlieue 13, which tells the story of a neighborhood on the outskirts of Paris that is totally abandoned by the government, with schools closed, drug trafficking, and politic corruption, a reality in no way different than that of Rio de Janeiro favelas.

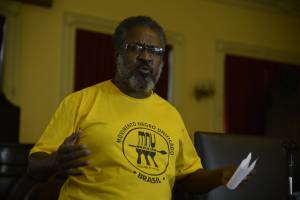

In the search for characters who keep up resistance and preserve the culture of this modern quilombo, which today is one of the blackest favelas in Rio de Janeiro, I spoke with Marcelo Dias of the Unified Black Movement. Marcelo was born and raised in Vila Cruzeiro. His father, from the state of Espírito Santo, and mother, from the state of Minas Gerais, left those states to live in Rio de Janeiro. Dias says that Vila Cruzeiro was one of the destinations chosen by blacks after abolition, which, in Brazil, was marked by the absence of public policies to fully insert black people in society.

In the search for characters who keep up resistance and preserve the culture of this modern quilombo, which today is one of the blackest favelas in Rio de Janeiro, I spoke with Marcelo Dias of the Unified Black Movement. Marcelo was born and raised in Vila Cruzeiro. His father, from the state of Espírito Santo, and mother, from the state of Minas Gerais, left those states to live in Rio de Janeiro. Dias says that Vila Cruzeiro was one of the destinations chosen by blacks after abolition, which, in Brazil, was marked by the absence of public policies to fully insert black people in society.

“Vila Cruzeiro, which grew without giving up our culture, is a consequence of the abandonment of our people by the Brazilian State. I grew up being part of that. I feel proud, because somehow I helped with some advances,’’ says Dias, who has been elected twice to Rio de Janeiro’s state congress.

Dias also spoke of how black culture was maintained and remains alive in the daily lives of Vila Cruzeiro residents. He talked about his childhood and about bathing in the favela’s natural pools, which became more widely known through several newspaper reports. “In the Cantareira quarry there were several natural pools; there were a lot of fish. The company there is also responsible for the devastation of the natural wealth of that place.” The company to which he refers is Lafarge, which extracts gravel, a raw material for the production of concrete.

Another important form of culture, the result of the influence of enslaved Africans brought to Brazil, so marginalized in our country, is capoeira. Masters Dentinho and Touro, two brothers who came from the state of Espírito Santo, residents of Street 3, were introduced to capoeira in Penha. And they were some of the first people to take capoeira abroad. Mestre Dentinho created his own style of capoeira called Angola da Penha, a fearless style, impossible to copy, that does not allow opponents to predict moves. He died in 2017. One of his most striking phrases: “I didn’t get rich, but I enriched a lot of people with my art.” He dedicated his life to capoeira and was responsible for the training of many black capoeirista practitioners. Today, capoeira is no longer criminalized or persecuted and has become a source of wealth for many who are not black and do not come from these places of resistance.

Mestre Touro, the brother of Mestre Dentinho, works to this day teaching children in Vila Cruzeiro. Due to the difficulties of making a living solely from capoeira, he was also an actor. The greatest legacy of these two brothers was to keep the true history of capoeira alive, preserving the memory of facts and dates that marked the survival of black people in Brazil. It is no coincidence that Mestre Touro is considered a living legend of Rio de Janeiro capoeira and continues to resist from inside Vila Cruzeiro.

Black music is another legacy of black people in Vila Cruzeiro. The famous Gaiola funk party made DJ Renan da Penha famous across Brazil. Unfortunately, as historically happens with funk artists from Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, the price paid for fame was an accusation of association with drug trafficking followed by arrest. Black music has always been marginalized. Samba is another example, and is another rhythm that is strong in Vila Cruzeiro and surrounding areas, which was kept alive through Cacique de Ramos, through the samba school Imperatriz Leopoldinense, and through the children of Jurema or Rouxinol of Grotão da Penha.

Dias also says that, as a young man, there were some groups in Vila Cruzeiro that danced to so-called black music, which spread African-American influences worldwide. Dias talks about something that is common in the favelas: “In the 1970s, in our group there were some white people that went to these funk parties. Segregating was never been part of our culture, especially in the favela.” Dias’s group was called Power of the Black People.

You cannot talk about Vila Cruzeiro without mentioning a character who was successful on soccer fields around the world, and generated lots of controversy outside them. Adriano Leite Ribeiro is the most well-known figure from the community. His story resembles that of thousands of young black favela men who dream of their moment in the sun. Ribeiro never abandoned his origins and spread the name of the favela internationally. But according to Dias, the community’s “Field of Order”, where Adriano the Emperor took his first kicks, was also a stage to master players as good as or even better than Adriano, who ran into violence and a lack of opportunity. “The twin brothers José Carlos and Antônio Carlos, Tuniquinho, Beto, Dedé, Tchê, Marrom, Garrafa, all of them black and from Vila Cruzeiro, were just as good as Adriano the Emperor. Jony, who was a professional in Paraná and died of thermal shock after diving into a pool, was another ace. This field has a history,” he says.

Another form of black culture present in the day-to-day life of the favela takes place in beauty salons. Dias recalls that his mother crossed to the other side of the favela to take care of her hair, a frequent practice in the homes of black women in the favela, even before there were beauty salons. “My mother has always gone to women who attended to clients at home. This was very common in the favela. Women worked during the week and on weekends they looked for hairdressers who attended to clients at home. Only later did beauty salons appear.”

Dias also says that there was strong activism in Vila Cruzeiro in his day. He recalls an old problem in the favela, the lack of electricity. The utility, Light, supplied energy to the Electricity Commission, and the commission transferred energy to the favela. When it rained, the power went out. And there were yet other energy supply problems in Vila Cruzeiro. “When I was 20, I worked at the Rio subway, I was secretary of the Vila Cruzeiro Residents Association, and I was part of the Workers’ Party. We started to put pressure on Light, and the company demanded that we gather together a certain number of residents. They thought that people would not go. We created a newspaper called WITH A MOUTH IN THE WORLD, we spread news by word-of-mouth to people’s homes, and in the end, we organized an assembly of 4,000 people in the square to discuss public policies. To this date, no one has achieved this in the favela.”

Teacher Laís Rufino has worked since 2009 at the Brandão Monteiro Public School, which is inside the favela. Her family has lived in Vila Cruzeiro since the 1930s and 1940s. She, who always spent her holidays there, knows very well the history of the quilombo that became a favela. “I always wanted to know the history of my family and the place where I chose to work. Many teachers go to the favela without this connection that I already had. I like to tell this story to the children and show that the place where they live is a place of resistance, that it was a quilombo and that they must maintain that resistance. Furthermore, this story serves as a counterpoint to the negative image of Vila Cruzeiro portrayed in the media. This story says a lot about who we really are,” says the teacher, who now works as the pedagogical coordinator of the school.

Vila Cruzeiro’s history is a portrait of what happened in Brazil after abolition: the country abandoned a people who were enslaved for three and a half centuries and did not receive any kind of compensation, nor were they contemplated with public policies for better insertion in society. The transformation of the quilombo into a favela marked by the stereotype of violence is due to abandonment and neglect. Today, favela residents are held responsible for the inequality in which they live. In Brazil, it is common to try to erase the stories of resistance. They erase the past of these favelas and expose only violence in an attempt to justify the war on drugs. But nobody expects people like Marcelo Dias, William Reis and Laís Rufino to emerge, who research the past to tell the real story of the favela. It is fundamental to rescue the culture and black influence in these places and reaffirm their strength and importance when teaching people who were born or live there. The favela has principles that are hard to find outside of it. Long live Vila Cruzeiro and all of its history of resistance!