This article is published as part of Brazilian Black Awareness Month, celebrated every November around Black Consciousness Day on November 20. It is part of our reporting partnership with The Rio Times. For the article as published in The Rio Times click here.

Rio’s Urban Peripheries Literary Festival (FLUP), which has taken place since 2012 across the city’s favelas and public spaces, designed its 2020 edition in homage to two “foundational black Brazilian female authors,” Carolina Maria de Jesus and Lélia Gonzalez. Maria de Jesus’s 1960 Child of the Dark chronicles daily life in a favela of São Paulo, while Gonzalez was an influential anthropologist, PUC-Rio professor, political activist, and theorist from the 1960s through the 90s. She is considered one of the main—if not the number one—black feminists in Brazil.

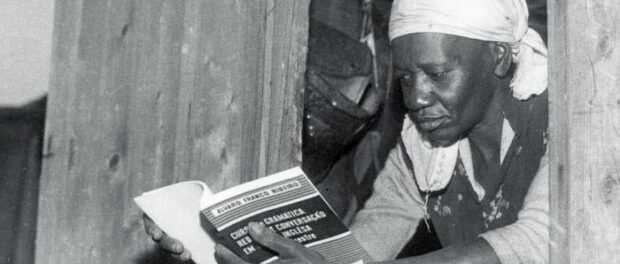

Though Maria de Jesus became internationally famous, she was never wealthy, nor was she able publish most of her work. Only four of her books made it to the general public and generated income for her while she was alive, from piles of notebooks she had written. Most of her work was published only decades after her death and some is still being published. Some of her notebooks are scattered throughout Brazil. They will be organized by her daughter Vera Eunice de Jesus and the writer Conceição Evaristo, in the hopes of bringing justice to her legacy.

Similarly, Lélia Gonzalez’s voice and theories have echoed across Latin America—and beyond—for over 50 years, but only two of her books were published in 1980s, while she was alive. Until now, there has never been a publisher willing to work with her extensive writing on the condition of black women and of black and indigenous populations in Latin America. One of her seminal works, “For an Afro-Latin American Feminism,” has only recently made it into a book, a just-published essay collection gathering her writing from three decades.

Two prominent voices of black Brazilian feminism today, philosopher Djamila Ribeiro and feminist studies scholar Carla Akotirene, discussed Gonzalez’s work at a recent FLUP 2020 digital event moderated by O Globo journalist Flávia Oliveira.

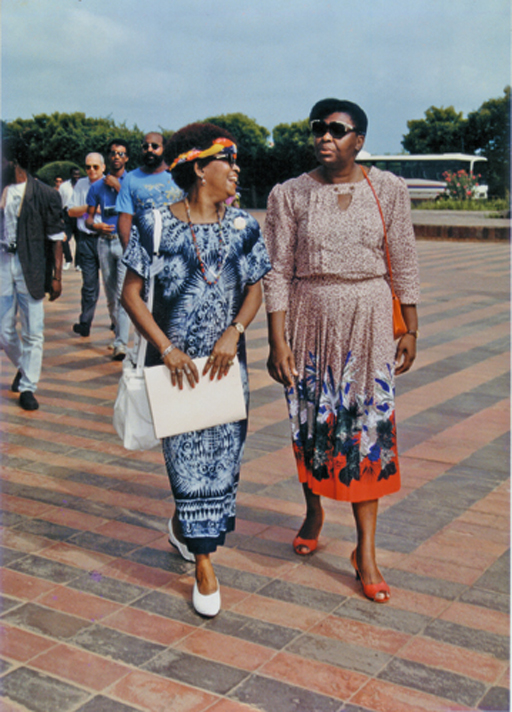

Gonzalez was active internationally over decades and influenced generations of black intellectuals, including thinkers such as Angela Davis—who told a crowd of Brazilian fans last year “I learn more from Lélia Gonzalez than you could ever learn from me.” Gonzalez coined the term “amefricanidade” for the experiences both of black people and colonized indigenous peoples in the Americas.

At the virtual event, Ribeiro said that reading Gonzalez for the first time felt like the world “opened up to me” through an understanding that “it was possible to think and assert oneself from the very perspective of a black woman.”

Gonzalez’s writing, Ribeiro points out, strengthens an intersectional perspective on feminism: the recognition “that black women live in a racialized gender,” she says, is part of a “fight against all forms of segregation…A revolutionary movement is not a way to fight for something that interests you, but for a project of society.”

Increasingly, the ideas of black Brazilian feminism are gaining traction in wider society—evidenced not only by the choices of the writers honored at FLUP this year, but also by last weekend’s local elections, where black women were among the most-voted city council candidates in state capitals across Brazil.

Gonzalez, who died in 1994, was emphatic that transformative feminism should not only be written about through complicated academic language. She wrote often of the importance of informal grammar she called pretuguês, a mix of “black” and “Portuguese.” Ribeiro described this as “epistemological courage” and an essential step towards the process of decolonization, recognizing “the linguistic legacy of the African peoples,” including to the central role orality plays when it comes to African-rooted knowledge production. Some of her friends used to say “Lélia was a griot, she was very talkative,” distancing Gonzalez and her production from a Eurocentric ideal. Griots were the traveling poets of West Africa.

Akotirene sees Gonzalez’s work as part of a larger project of recognizing the groundbreaking contributions of black Brazilians who are too often not credited for their ideas. It is important, she argues, to emphasize that this nullification and invisibilization of the intellectual capacity of those who are oppressed allows for a consecration of their criminalization.

Gonzalez, a PhD in anthropology, was active far beyond the academic sphere, which Ribeiro and Akotirene described as a lesson for political thinkers and activists today. In particular, they spoke of the importance of social media. Ribeiro said that being derided as a “little blogger” in the past has not changed her conviction that “social networks allow us to communicate with people indiscriminately in a world where knowledge is for the few. We must democratize knowledge.” Akotirene said that this creates possibilities so that a “domestic worker gains access to information.”

The panelists pointed out that both Gonzalez and Maria de Jesus are examples of what writer Conceição Evaristo named escrevivência. This is a black method of writing about their own people, made of three elements: body, condition and experience. It unites the subjective dimension of the black being, her representation, and her body.