This is the first of two articles on the criminalization of funk music and oppression of black favela culture. Read part 2 here.

The Judiciary and the Criminalization of Funkeiros

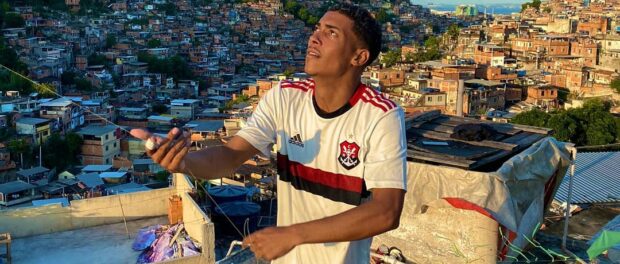

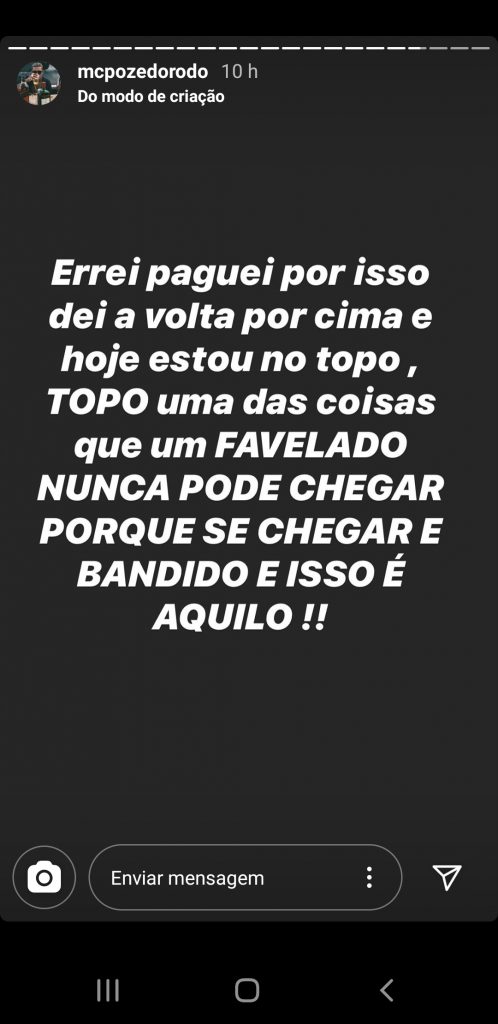

“Let the favela win, shine, and don’t try and destroy this!!” and “I made mistakes, I paid for them, I turned things around, and now I’m at the top. The top, where the guy from a favela can never be, because if he gets there, he’s a gangster”—these are the writings on the Twitter and Facebook profiles of Marlon Couto da Silva, 20, the singer MC Poze do Rodo, also known as the Pitbull of Funk, right after charges were pressed against him for association with drug trafficking, promoting crime and corruption of minors. The charges were presented by the Rio de Janeiro court of justice (TJ-RJ) and accepted by the Rio de Janeiro public prosecutor’s office (MP-RJ), and his provisional arrest was decreed.

Deixa a favela vencer brilha e não tenta destruir isso !! 😞

— Mc Poze Do Rodo 🚩🎶 (@McPozedorodo) July 7, 2020

Let the the favela win, shine, and don’t try to destroy this!!

The relation between the singer and the judiciary had intensified beginning in September 2019. MC Poze, along with five other people, was arrested in the city of Sorriso, in the state of Mato Grosso and transferred on September 28 to the Pascoal Ramos prison in Cuiabá, as a way of guaranteeing public order. Poze, who was performing in the city, was arrested in a hotel with two other people from his team. According to the local judiciary, the singer was initially temporarily detained, a measure which was then turned into a preventative arrest and accepted by the Mato Grosso Court of Justice. The indictment was for the following allegations: “drug trafficking, being part of a criminal organization, association with drug trafficking, incitement and promotion of crime, corrupting minors, and supplying alcohol to minors.”

The Mato Grosso police arrested the singer at a party at which he was due to perform. At the party, according to the Mato Grosso Military Police, small quantities of marijuana and cocaine were seized, and there was lots of alcohol. There were between 39 and 43 teenagers on the premises. The concert tickets were seized. The police officers did not clarify whether, what kind of, or what quantity of, an illegal substance was seized in the MC’s possession. Nevertheless, Poze and five others were arrested on the same charges, disregarding the legal principle of individualized charges.

The funkeiro’s (funk artist) legal defense argued in their habeas corpus request that the arrest of the MC, who is from Santa Cruz in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, was an example of the criminalization of funk, of the favela, and of the peripheries and favelas’ artistic class. Their position—and that of defendants of innumerable other funkeiros—is the same as that of the Committee for the Defense of the Democratic State of Law of the Rio de Janeiro chapter of the national bar association (OAB-RJ), which produced a report outlining the racism which structures the criminalization of favela culture, from capoeira, samba, and jongo to rap and funk, as a legacy of slavery. This argument was accepted, and the singer was ordered released.

The judge accepted the argument of Poze’s defense, ruling that the measure in place was “disproportional” and “exaggerated,” and that the individual under investigation should have his right to defense and freedom guaranteed. As noted in the files: “Preventative arrest, according to the interpretation in line with the constitutional profile, is an extreme measure that can only be used if its rigorous indispensability is proven, based on concrete motives which indicate the necessity of segregation.”

The scenario faced by Poze is not something new to Rio de Janeiro funkeiros. Other artists from the funk movement have already been arrested, had their work equipment seized, or even had bailes funk (funk parties) closed down, and been banned from nightclubs and party, concert, or event venues. The 1990s in the city of Rio de Janeiro were strongly marked by these effects of the criminalization of the funk movement. The owners of the main sound crews of the time, ZZ productions and Rômulo Costa from Furação 2000, were indicted and arrested. In parallel with the persecution and arrest of the leaders of this artistic movement, approximately 30 bailes funk were closed down in the whole state of Rio de Janeiro, thanks to a parliamentary investigative commission (CPI) which investigated funk culture and music.

To MC Poze, the young funkeiro with four million followers on social media, who was raised in the Rollas Favela in Santa Cruz, music is his profession. In July 2020, his life was once again splashed across the newspapers with accusations made by the public prosecutor’s office in Rio de Janeiro, claiming that the singer was involved with drug trafficking and was a part of the Red Command (CV) gang.

To MC Poze, the young funkeiro with four million followers on social media, who was raised in the Rollas Favela in Santa Cruz, music is his profession. In July 2020, his life was once again splashed across the newspapers with accusations made by the public prosecutor’s office in Rio de Janeiro, claiming that the singer was involved with drug trafficking and was a part of the Red Command (CV) gang.

Because he testified that he had previously been involved in the drug retail trade when he lived in Rollas between 2015 and 2016, in a new investigation, prosecutors claim that the singer was part of the criminal gang due to his March 2020 performance in the Jacarezinho favela at an event which celebrated a man linked to the Red Command. However, Poze and his lawyers point out that on the same night, the MC performed other concerts, in different venues, even in areas controlled by other gangs, which disproves the theory that he is involved with the CV gang for having performed in Jacarezinho.

Stigmatizing narratives such as these contribute to the criminalization of funk culture and favela youth. They are part of the puzzle that constantly links funkeiro youth to violence and the drug trade in Rio de Janeiro and other cities in Brazil. What Poze do Rodo has experienced in relation to the Brazilian judiciary is not anything new for those who have chosen funk as their source of income or main leisure activity. Unsurprisingly, the 1990s were marked by the association of famous mass muggings on Rio’s beaches with black funkeiro youths from the favelas, with various stereotypes being constructed around young people from favelas and peripheries. The 1990s and 2000s saw a lot of public and police interference in the carioca funk movement, as well as in the rap movement from São Paulo.

Investigations, accusations, indictments, and arrests of artists, as well as the prohibition of cultural funk events in the favela have grown more and more common, becoming normal. This movement against funk reached such a point that the legislature began discussing two proposals legislating funk music. One wanted to ban funk music nationally and was presented in 2017 to the Federal Senate, through a popular suggestion of legislative discussion, under the argument that funk is a “public health crime against children, teenagers and the family.” The other proposal aimed to recognize funk as a form of carioca cultural heritage, and was presented within the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) in 2009. The first was rejected and the second approved. But structural racism re-organizes itself and continues its dominance.

The Last 20 Years in the Funk Movement

Over the last twenty years, from time to time, funk professionals have been arrested under allegations of being involved in drug trafficking and promoting drugs, the trafficking industry, and for weapons, while they were merely portraying the reality of the favelas and peripheries nationwide, based on the supposition that freedom of expression is guaranteed for all.

Symbolic judicial decisions on funk culture, however, point to the contrary. Emblematic cases, with the same type of repeated abuse of authority and unfounded accusations, abound on the carioca funk scene. The cases of the funkeiros Rômulo Costa, MC Colibri, MC Sapão, MC Galo and many others are examples of this criminalization. In the majority of these cases, the supposed links with drug trafficking were either not fully proven, or were proven in a doubtful or insufficient manner. Some, like MC Sapão, were released after months in prison due to lack of evidence or the weakness of the court case. Meanwhile others remained imprisoned for years, like MC Colibri.

However, in response to this targeted repression, there is solidarity from the funk scene. Despite the high levels of prejudice against people who have served time in prison, there are those who have experienced the same situation, gone through the same prison, and who try and help. MC Colibri says: “As soon as I was out of prison, MC Marcinho created a funk song for me. But since then, I’ve only come across closed doors. It was hard [to find] a DJ who wanted to display my work, someone who wanted to employ a man who had served time.”

On November 25, 2010, this situation changed with the Rio de Janeiros state Military Police implementation of its pacifying policy, through the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs). The invasion and occupation by military troops of the Penha and Alemão favela complexes, with a strong media endorsement, marked the start of a new era in Rio de Janeiro security policy. A policy of former governor Sérgio Cabral, who is now behind bars for corruption and money laundering, the UPPs were launched under the idea that they would exterminate the armed drug trade in some of the city’s favelas.

According to the official line, along with tanks and bullets, democracy and freedom entered the favela. This was just talk, as days after the Alemão and Penha favela complexes were occupied by army and police troops, the assault on favela culture intensified: MC Tikão, MC Frank, MC Dido and MC Smith, all fairly well-known on the carioca funk scene, were arrested. The reason: for singing and composing their own funk lyrics, narrating the reality and the historical memory of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, in songs known as the “proibidões” (a funk sub-genre, literally “strongly banned”). Up until they were put in prison, at the police station, they sang. Freedom of expression and of artistic production, some would say, but nevertheless, they were arrested.

It would not be this time that democracy and freedom entered the favela. Risking arrest, like what MC Dido suffered when he, born and bred in Morro do Borel, sang sentences including “UPP [swearing], leave Borel!”, is not freedom. At most, this is an inelegant political criticism, but even so it is fully guaranteed under Brazil’s Federal Constitution.

MC Tikão, MC Frank, MC Dido and MC Smith were accused by the Civil Police of crimes such as incentivizing crime, association with drug trafficking, being part of a criminal organization, amongst others. When the singers were arrested, the police chief even accused the funkeiros of being part of the CV gang, which dominated the Alemão favela complex at the time of the occupation in 2010. In an interview, delegate Sardenberg, who was responsible for most of these arrests, said that “drug trafficking has a voice” and that the MCs are like any other workers in the drug trade. The media and the police itself said they are not “against funk: good funk.” This moral judgement has been highly criticized, including within the Civil Police.

The arrest of the funkeiros is part of a long history of criminalization of black favela culture and of denying legitimacy to black music genres from the favela and the periphery. After the cases were given visibility and lawyers took legal action, the MCs were released through habeas corpus writs granted by the Brazilian Supreme Court.

The arrival of the UPPs in favelas was evidence of an anti-funk and anti-favela culture wave, in more general terms. Following this trajectory, various cultural centers in occupied favelas began to be surrounded by the UPPs, which used a resolution from the Security Secretariat to impede artistic and cultural expressions in the favelas where UPPs had been set up. In some areas under the control of the UPPs, for example Chatuba da Penha, funk balls were banned under Resolution 013, which was a norm in Decree 39,355/2006, which was updated in 2007. The decree established that any artistic, social or sporting event in the state of Rio de Janeiro required the authorization of the commander of the Firefighting Force (CBMERJ), of the State Secretariat of Civil Defense (SEDEC), of the commander of the local battalion of the Military Police (PMERJ), and of the current chief-officer of the Unit of Administrative and Judiciary Police (UPAJ) of the Rio de Janeiro Civil Police.

In light of this, the favelas and peripheries with UPPs had their baile funks silenced as the UPP commanders did not grant authorization for the parties, despite the fact that the 1988 Federal Constitution eliminated any form of artistic censorship and limitations of the right to gather by any authority at any level of hierarchy.

Around nine years later, cases of persecution and criminalization of funk professionals have not changed. In 2019, DJ Rennan da Penha was accused by the Civil Police of taking part in a criminal organization as “scout” or “activity”, because, according to the judiciary, he described the police’s movement in the Penha favela on his social media channels.

When he was interviewed on December 12 in the Conversation with Bial program on the Rede Globo TV network, the singer Rennan da Penha said: “I’ve travelled to Egypt, Mexico, a few countries, I was going to go on tour in Europe, the US. Out of nowhere, they took everything from me. What happened could have been the end not only of my life, but of my whole career. I have 11 years of experience in funk, I fought hard to get where I am.”

DJ Rennan da Penha remained under arrest for seven months, right when his career was growing fast and was gaining more visibility both within and beyond the Complexo da Penha and across the country. However, it was only after the decision by the Supreme Court on imprisonments after first appeal that the DJ succeeded in being freed.

Entities linked to the legal profession criticized the case as an inversion of the law: “The case of DJ Rennan, therefore, is an example of an enforceable judgement in which, in practice, an unfounded inversion of the burden of proof took place. This is because the prosecution did not actually prove the concrete practice of the imputed fact with the details of its circumstances. It was the judge who, based on unjustified inferences of evidence—which lacked a base in knowledge—completed the logical path that should have been taken alone by the prosecution.”

These young artists face quite similar accusations, which are also similar to those faced by any other criminalized funk artists. Two of them, DJ Iasmin Turbininha and DJ Polyvox (the creator of the 150 BPM, an accelerated funk beat), were also summoned to testify, but they were not arrested, unlike their colleagues Rennan and Poze. In the case of Iasmin, the only female black DJ from a favela to dominate the funk scene with visibility in Rio and to be criminalized, the artist and other professionals who accompanied her needed to set up a crowdfunding campaign to cover the costs of her legal defense. Polyvox’s lawyer said that the artist was called in to testify by the police chief who was trying to discover who financed the baile funk in Nova Holanda, in Complexo da Maré.

In an interview with the website Z Matéria, Polyvox’s lawyer Dr. Estevan said, “Everyone regrets the culture of discrimination towards funk, which unfortunately involves the bailes in favelas, ceasing to consider them a cultural expression of the Rio de Janeiro people and which is persecuted, precisely when professionals who commercialize their musical performances are asked to be heard in procedures of criminal investigations.”

More recently still, on October 29, 2020, two Rio de Janeiro MCs were summoned by the Civil Police in an investigation into promoting crime: MC Cabelinho and MC Maneirinho. In this case, MC Cabelinho himself recognizes the racism which has underpinned this entire process of criminalizing funk, for decades:

FÉ!! QUER QUE EU CANTE SOBRE O QUE? QUE EU FALE SOBRE O QUE? EM MUITAS DAS MINHAS LETRAS RETRATO O QUE EU VI E VIVI, O COTIDIANO VIOLENTO DA VIDA DE TODO MORADOR DE COMUNIDADE, E PODE TER CERTEZA QUE ATÉ QUANDO EU PUDER VOU CONTINUAR FAZENDO ISSO. #FOGONOSRACISTAS pic.twitter.com/S6QDy4N90g

— LITTLE HAIR (@cabelinhomc) October 29, 2020

Faith!! What do you want me to sing about? What should I talk about? In many of my lyrics I portray what I have seen and lived, the violent daily life of any favela resident, and you can be sure that I will keep doing that for as long as I can. #Firetotheracists

And, as mentioned above, on the same date, October 29, 2020, another funkeiro, the artist MC Maneirinho, found out that he was being investigated for promoting crime. He made a statement in an interview, saying: “To tell the truth, I can’t even believe this is real. Is the police going to investigate Wagner Moura for playing the role of Pablo Escobar [on screen]? Does it go after the playboys [privileged young men who follow the latest trends] who head in to the favela to recount what goes on there in documentaries? I’m an MC, I portray what happens in the communities, that is my art…”

The musician lamented to his followers on social media what he classified as “cowardice”:

É COM MUITA TRISTEZA NO CORAÇÃO QUE VENHO INFORMAR TODOS MEUS FÃS E AMIGOS, QUE FUI SURPREENDIDO ESSA SEMANA COM UMA INTIMAÇÃO. ESTOU SENDO ACUSADO DE APOLOGIA AO CRIME. PEÇO MEUS SEGUIDORES E AMIGOS DA MUSICA QUE AJUDEM NESSA. NÃO POSSO SER VÍTIMA DESSA COVARDIA 🤬 pic.twitter.com/ucZ0hxecMJ

— MC MANEIRINHO (@mc_maneirinho) October 29, 2020

It is with much sadness in my heart that I inform all my fans and friends that I was taken by surprise this week with a [police] summons to give evidence. I am being accused of promoting crime. I ask my followers and friends from the music scene to help with this. I cannot be a victim of this cowardice.

Asking why young funkeiros bother the police, the judiciary, and other powers that be in Brazil, must be a part of the anti-racist struggle. Removing blame from youth who promote cultural and artistic displays in their favelas and peripheries, as well as in the wealthy neighborhoods of cities, must be at the heart of the anti-racist agenda. It is necessary to understand what underlies the State’s constant actions in relation to the criminalization of favela culture. And to also understand how these favela artists feel about the accusations that they face, which change their lives forever.

This is the first of two articles on the criminalization of funk music and oppression of black favela culture. Read part 2 here.

Ingra Maciel, a resident of Acari, is 28 years old and has a history degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and a postgraduate certificate in teaching the history of Africa from Colégio Pedro II. She is currently a research assistant at UFRJ’s Medialab. During her undergraduate degree she developed her research on the criminalization of carioca funk and its process of resistance, and she is currently studying carioca funk from a pedagogical perspective.