This article is part of our reporting partnership with The Rio Times. For the article as published in The Rio Times click here.

Rio de Janeiro’s wealth of artistic talent includes many under-represented voices from favelas, whose work should and can be available to a wider audience with the right coordination and support, according to a coalition of historians and favela artists who spoke at the first City, Favela, and Heritage Forum. The Forum’s 2020 three-day Annual Meeting discussed the challenges and possibilities of such coordination.

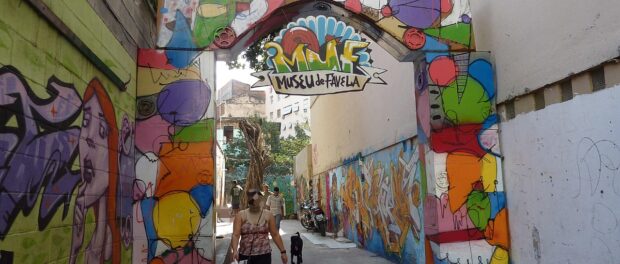

The meeting was included in the program of the 27th World Congress of Architects, scheduled for 2020 in Rio de Janeiro but delayed to 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic. At November’s virtual Forum, realized by the Favela Museum in the favelas of Cantagalo and Pavão-Pavãozinho, overlooking Ipanema, guests were invited to discuss proposals for building a more integrated city, strengthening an effective network in the field of public heritage, and developing policies for sustainable urbanism. The meeting also included performances—shared virtually—of favela artists such as Misturando Som, Ludi Um, and Coletivo Amas de Leite.

The Forum aims to uplift work like that of Dona Tuca, an 85-year-old favela poet who began writing poetry on pieces of paper that she brought to her friend, retirement home worker Valéria Barbosa. Barbosa kept the pages and bound them together to offer back to her poet friend. Soon after, Dona Tuca won an award for her writing, and the money from the award was used to produce copies of her book of poems.

Over the course of their Annual Meeting, the Forum worked together to construct a common agenda that could amplify voices like Dona Tuca’s and those of the favela artists that performed during the event and are still unknown to a wider audience.

One key reason these artists are not more widely known is their lack of resources to pursue arts. Members of Women of Stone—a women’s collective from the West Zone of Rio that has worked with arts and culture for nearly two decades—emphasized that while the pandemic may have given favela residents reason to stay indoors, the possibility spending time writing or painting feels far off for those on limited incomes.

Valéria Barbosa, creator of Favela Soiree, shared the same concerns, asking: “Dona Tuca was able to buy a cabinet to keep her copies, but without having them in bookshops, how is she going to sell them?” Dona Tuca, who lacks a phone and is too old to carry her books in a backpack and sell them door-to-door, might have the time to write during her retirement, but she lacks opportunities to sell her book.

To overcome this issue, speakers at the Forum pledged to use social media to support cultural events run by favela residents and work toward establishing cultural infrastructures in favelas. In addition, they committed to mapping the cultural work being done in favelas, which is currently promoted in a scattered way.

Architect and urbanist Wagner Vils described how land titling in favelas is crucial for favela-based organizations to register as businesses and better organize the money they receive for their art, using it to foment more creative work. “When you have the title to your land, [there is more] possibility of developing a center—you need administrative help, there is the issue of tax breaks, of access to financing—and this [lack of title] makes it a little more difficult for favelas to be centers that can attract more investments, in any area.”

Eber Marzulo, a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul and coordinator of its Identity and Territory Research Group, brought up an additional point: he said that favela residents also have the right to demand public investment and funding of what they consider important to be preserved. “Brazil has one of the least fair tax systems of the planet, in which everyone pays the same percentage, so if we all pay taxes, we have the right to demand more from the State,” he said.

Eber Marzulo, a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul and coordinator of its Identity and Territory Research Group, brought up an additional point: he said that favela residents also have the right to demand public investment and funding of what they consider important to be preserved. “Brazil has one of the least fair tax systems of the planet, in which everyone pays the same percentage, so if we all pay taxes, we have the right to demand more from the State,” he said.

“Public policies deliberately neglect the favelas,” said Marzulo, adding that the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the challenges they face. This opinion was widely shared among event participants. Many collectives in favelas had to reinvent themselves in order to take care of residents’ basic needs, distributing basic foodstuffs and hygiene kits to families who could not afford them.

Over the course of the pandemic, favela activists have stressed that it’s important not to let feelings of solidarity stop them from holding government officials accountable for work that needs to be done. In an online teach-in about memory in favelas held earlier this year, Maria da Penha of Vila Autódromo‘s Evictions Museum said, “We cannot stop thinking about government policies, because we have to understand that we are their bosses. We have to make demands of them! We are the poor who give them money and labor.”

In line with this, Renata Santos of the City, Favela, and Heritage Forum concluded that its team should commit to monitoring the public institutions responsible for policies on heritage: “At the moment, we can’t even check who on the city council is responsible for heritage, so we should aim at monitoring that regularly.”

The Forum hopes that with these proposals, they can leverage the work of artists such as Dona Tuca and challenge the way Rio’s favelas are featured in the city’s mainstream cultural scene.