This is the latest contribution to our media watchdog series on the Best and Worst International Reporting on Rio’s favelas, part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing conversation on the media narrative and media portrayal surrounding favelas.

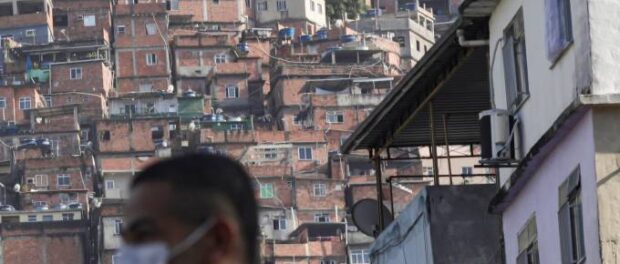

The coronavirus pandemic, and responses to it, dominated coverage of Rio’s favelas in the international media in 2020. Coverage focused on the specific challenges favelas face in preventing the virus, the virus’s advance through these communities, inadequate government responses, and community-led efforts to safeguard residents’ health and well-being. Many pieces did an excellent job of sourcing from local leaders and documenting responses that were spearheaded by them, while some fell into dangerous and unverified stereotypes, as detailed below.

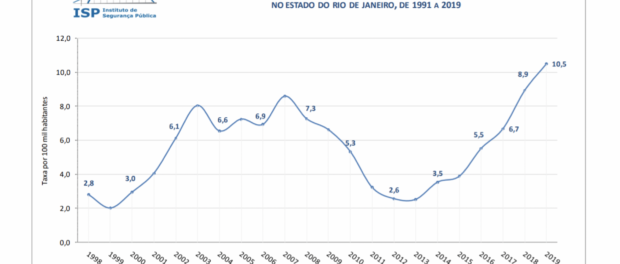

A handful of reports provided important coverage of the mounting deadly abuse of force by Rio’s police department, even as the pandemic began—in April, Rio police killed 43% more people than they did in April 2019—and the subsequent Supreme Court case that banned police operations in favelas during the pandemic. International media also touched on nationwide antiracist organizing and its parallels with similar activism in other parts of the world.

Since March 2020, according to the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard,* at least 28,110 of Rio’s favela residents have had Covid-19, with over 3000 perishing with the major culprit being the lack of adequate response from city, state, and federal government officials. Severe underreporting has been a critical issue. While incoming mayor Eduardo Paes has pledged to take the pandemic more seriously—and was resoundingly endorsed by voters facing an alternative of a second Marcelo Crivella term—Paes’s record on forced evictions and the gentrification of the city that occurred during his 2009-2016 tenure as mayor require a sharp media eye on how favela residents will fare as he returns to the helm.

The international media covered the broad results of the 2020 Municipal Elections, a referendum of sorts on pandemic responses—including Bolsonaro’s narrative on the pandemic—and on social welfare. Bolsonaro’s disregard for and lack of interest in managing the crisis in an effective science-driven manner, referring to the virus as “just a little flu,” are now world famous. The media also covered the fact that Bolsonaro, who has always been a strong opponent of social policies such as Bolsa Família, was compelled by popular pressure to approve a monthly R$600 (US$115) emergency stipend for all those who are not formally employed, with a value of R$1,200 (US$225) for informally employed single mothers.

Paradoxically, during the pandemic, this emergency aid had a positive impact in the president’s approval ratings, bringing them to an all-time high, even in regions where he has long been unpopular, such as the Brazilian northeast. The upcoming expiration of these benefits and their effect both on the welfare of Brazil’s poorest residents and on Bolsonaro’s political project deserve careful media attention. Bolsonaro, worried about the unpredictable impacts of the end of the emergency aid on his popularity, has called for a raise in the average stipend of R$190 (US$36) paid by Bolsa Família for the poorest Brazilians, backtracking on his own longtime rhetoric.

Best Reporting

Good discussions of the nexus of challenges faced by favelas amid the coronavirus pandemic include this Washington Post piece, which hears from a community health worker in the Borel favela, in Rio’s North Zone, and residents of Rocinha and Complexo do Alemão, as well as this Guardian piece, which looked at early—but already distinct—differences in abilities to protect oneself from the virus among Rios’s rich and poor.

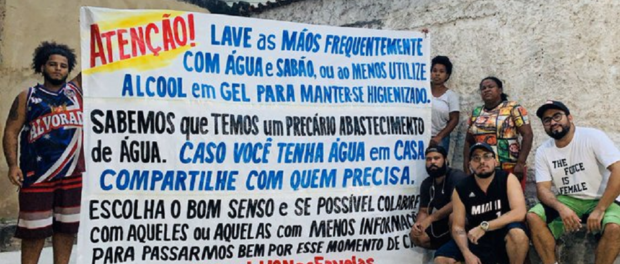

The most impressive improvement we saw in 2020 relative to reporting in past years was the much-deserved, high quality and ample coverage given to community-led responses to government neglect, in this year’s case due to the coronavirus, including must-read pieces in The Guardian (which also produced this excellent video), Slate and the BBC and the Brazilian Report. Reuters covered deep cleaning efforts in Santa Marta, NPR spoke with a community leader in City of God, The Havana Times covered efforts by favela photographers, and an Americas Quarterly piece covered favela-based news outlet Voz das Comunidades’ app for sharing news about the virus geared to favela residents. OpenDemocracy published translated versions of articles by journalist Thaís Cavalcante of the Maré favela about how favela journalists are responding to Covid-19 and the fight for access to mental health in Maré; Cavalcante’s coverage of favela journalists’ work was also published in IJNet. The Sociable and The Response were among those who covered resident efforts to close the data gap about the pandemic in favelas. The AP covered sanitization efforts in Rocinha and how a samba school in Vila Vintem transitioned from sewing carnival costumes to medical masks and gowns, and a France24 piece on the pandemic features a physiotherapist who lives in Complexo do Alemão.

Covering public security, The New York Times provided crucial scrutiny of Rio’s record year of police killings, 2019, with a long investigative piece examining the consequences of Rio’s now-suspended governor Wilson Witzel’s hardline positions. A piece in Quillette takes a historical look at four decades of a failed war on drugs in Rio. After high levels of police violence grew further during the first months of the pandemic, a piece in YES! Magazine offered excellent coverage of the public outcry in the wake of the police killing of 14-year-old João Pedro Mattos Pinto in the Complexo do Salgueiro favelas in Greater Rio’s São Gonçalo municipality. The YES! piece also covers favelas’ protagonism in the Supreme Court case that resulted in a ban on police operations in favelas during the pandemic, which became known as the ADPF das Favelas.

Covering public security, The New York Times provided crucial scrutiny of Rio’s record year of police killings, 2019, with a long investigative piece examining the consequences of Rio’s now-suspended governor Wilson Witzel’s hardline positions. A piece in Quillette takes a historical look at four decades of a failed war on drugs in Rio. After high levels of police violence grew further during the first months of the pandemic, a piece in YES! Magazine offered excellent coverage of the public outcry in the wake of the police killing of 14-year-old João Pedro Mattos Pinto in the Complexo do Salgueiro favelas in Greater Rio’s São Gonçalo municipality. The YES! piece also covers favelas’ protagonism in the Supreme Court case that resulted in a ban on police operations in favelas during the pandemic, which became known as the ADPF das Favelas.

2020 also included coverage of positive news in favelas not directly related to the coronavirus: Medium’s Level looked at the media revolution happening in Brazil’s favelas, the AP did a story on favela residents’ efforts to green their communities, and Al Jazeera covered a ballet project in Complexo do Alemão.

We also noted excellent coverage on wider socio-economic issues in Brazil in articles that did not center favelas, but deal with topics that are crucial to favela residents. These include a deep dive Economist piece on the Bolsonaro administration’s downsizing of Bolsa Família payments before the pandemic, a piece in National Geographic on the double bind faced by Brazil’s domestic workers during the pandemic, and a discussion in Americas Quarterly on why U.S. protests for racial justice resonate so deeply in Brazil. The Brazilian Report covered Brazilians’ difficulty of accessing the federal government’s R$600 (US$115) per month stipend.

Worst Reporting

The incorrect stereotype that favelas are fully controlled by drug gangs and militias surfaced in two lines of coverage about the coronavirus pandemic. One characterizes drug dealers as central social welfare providers in this time of crisis. An article in Filter Magazine uses one interview with a Rocinha resident to assert that drug traffickers were playing a key role distributing groceries and bags of cash in the community in the face of the “scarcity of other help.” It is important to note that as Brazil’s largest favela, Rocinha is the size of a small city, with well over 100,000 residents. While the article mentioned some aid coming from NGOs and the federal government’s emergency stipend, it failed to mention the incredibly diverse and widespread efforts conducted by numerous Rocinha-based organizations, from being the first favela to issue its own case reporting, to its incredibly active community media, and partnerships between local activists and public health workers, which carefully identified high-need families and sustained aid efforts for months, engaging allies throughout the city. These citizen-led programs were a cornerstone of aid in the community for families falling through the cracks, in Rocinha as in other favelas across the city and country. These are likely what helped keep Rocinha from being the hardest-hit favela by the pandemic.

Video by Rocinha Resists Collective of the collective’s partnership with local health workers.

Another problematic generalization that surfaced was that of criminal gangs acting as public health enforcers in favelas, enacting lockdowns to slow the spread of the virus. An Ozy piece writes that “With President Jair Bolsonaro dismissing the pandemic as ‘sniffles’ and criticizing regional lockdown measures, the country’s drug gangs and paramilitary groups have stepped in to enforce social distancing to combat the spread of the coronavirus.” While there is evidence that this kind of messaging appeared from drug gangs in a handful of favelas, describing it as widespread is an irresponsible overstatement. The Ozy piece cites messages in two favelas, whereas there are some 1000 in the city. Meanwhile, as pointed out by sociologist José Claudio Souza Alves, an expert on Rio’s off-duty police mafias, or militias, which—rather than drug traffickers—increasingly control the city’s favelas: rather than enforcing quarantine, militias in many areas pressured for commerce and activities to remain open during the pandemic, as they benefit from extortion fees on commercial activities.

Looking Ahead to 2021: What to Keep an Eye On

While national plans for coronavirus vaccination are still up in the air, favela residents appear destined for many more months of disease risk, especially with the arrival of the British strain of Covid-19 this week. It is unclear when the pandemic-era ban on police operations in favelas will lift, and what violence may ensue. Already, a Supreme Court justice is questioning Rio’s government about a long line of operations that appear to have violated the ban.

Though the outcomes of Brazil’s local elections represent a small blow to Bolsonaro’s power, and since then, his ally, Rio mayor Marcelo Crivella, was arrested on December 22 for corruption allegations, the president remains popular as described above. How the incoming US administration led by Joe Biden responds to Brazil under his leadership is going to be a critical determinant of future outcomes across the country and important topics—from the environment to human rights and racial justice—even in local communities like Rio’s favelas.

Though the outcomes of Brazil’s local elections represent a small blow to Bolsonaro’s power, and since then, his ally, Rio mayor Marcelo Crivella, was arrested on December 22 for corruption allegations, the president remains popular as described above. How the incoming US administration led by Joe Biden responds to Brazil under his leadership is going to be a critical determinant of future outcomes across the country and important topics—from the environment to human rights and racial justice—even in local communities like Rio’s favelas.

Meanwhile, Mayor Eduardo Paes was inaugurated on January 1. His administration deserves close scrutiny, given its track record from 2009-2016 when Paes evicted some 80,000 cariocas–mostly favela residents—from their homes, spending the equivalent of tens of billions of dollars to redesign the city purportedly for the Olympics with little positive impact felt today. A close eye will need to be kept on whether he attempts to use the pandemic as a new pretext for forced evictions today.

On the socioeconomic front, residents of Rio’s favelas are due to face continued challenges with pandemic aid expiring and food prices on the rise.

Above all, international media coverage of favelas should continue to focus on how communities are responding to these unprecedented circumstances—which are ripe with positive examples for the rest of the world.

*The Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard and RioOnWatch are both projects of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).