This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.

Problems with electricity in favelas are chronic and emerged along with the favelas themselves. The State fails by delivering low-quality service, and residents, improvising, end up overloading grids and making the entire favela population suffer as a result. People spend days without electricity in their homes, food and appliances are lost, and according to residents, all of this gets worse in summer.

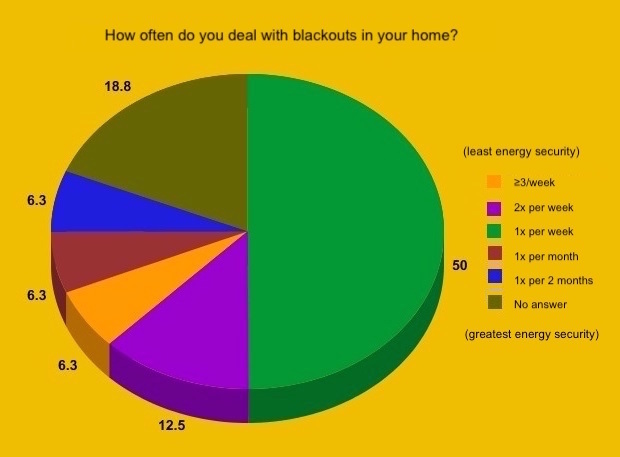

A survey* was conducted between March 4 and 24 by the Jacarezinho Favela Data and Narratives Laboratory (LabJaca) covering residents’ perceptions regarding electricity. The survey engaged residents of Jacarezinho, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, resulting in numbers that describe a scenario that is well-known and often discussed by residents. Among 40 interviewees, 50% state that they suffer blackouts at least once a week; 12.5% say they suffer blackouts twice a week; and 6.3% say they deal with the problem three times a week or more. In this scenario, 68.8% suffer blackouts at least weekly. Since 18.8% did not know how to answer, this leaves only 12.4% claiming that the electricity goes out less than weekly.

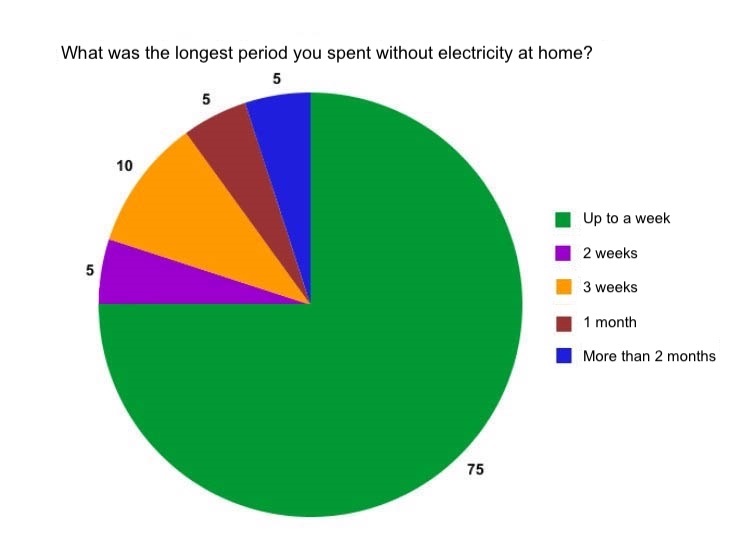

When asked what the longest period they had spent without electricity was, the result was abysmal: 25% of residents interviewed have experienced a blackout lasting more than one continuous week. This block was composed of: 5% who claimed to have had no electricity for two weeks, 10% who reported having no electricity for up to three weeks, 5% who claimed to have no electricity for more than a month, and 5% who claimed to have no electricity at home for more than two months, without anything having been done about it.

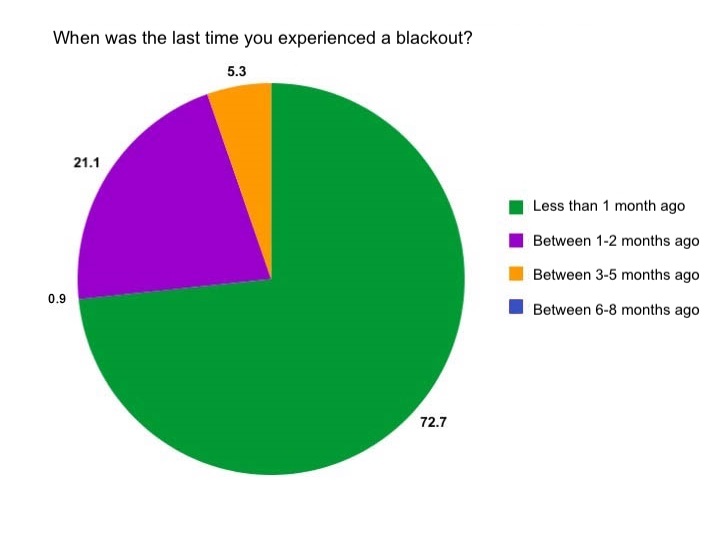

As we see in the graph below, 72.7% of respondents say they had no electricity at home at some point over the past month.

Picture the financial loss of spending days without electricity: at minimum, food in the refrigerator spoils, and, as often as blackouts happen in the community, many household appliances and electronics get damaged.

We also asked residents about this, and among those interviewed, only 36% suffered no financial losses from the blackouts. The rest are divided into a variety of problems: from the 42% who said they spend days without electricity and, therefore, lose food, to the 22% who reported that they have lost various household appliances such as refrigerators—the most frequent on the list—followed by freezers, computers, stereos, televisions, and other appliances that depend on being connected to electric plugs.

These problems are extremely serious and such losses are not covered by the State or by the company that manages Rio de Janeiro’s energy supply: Light. Following the principle of human dignity, the guarantee of access to electricity is a fundamental right, indispensable to ensure quality of life for Brazilian citizens. According to Article 22, of Law 8078 from 1990: “public agencies, by themselves or through their companies, service providers, or any other form of business, are obliged to provide services that are adequate, efficient, safe and, regarding those that are essential, continuous.”

However, despite this acknowledgment by law, the precarious supply of electric services in the favelas challenges the democratic State based on the rule of law that presupposes the guarantee of basic rights for the population. In the case of electric services for the favelas—as demonstrated by LabJaca’s survey in Jacarezinho—a quality service is not guaranteed. This only leads us to believe that, for certain social groups, this good is neglected.

Who Should You Turn to When this Happens?

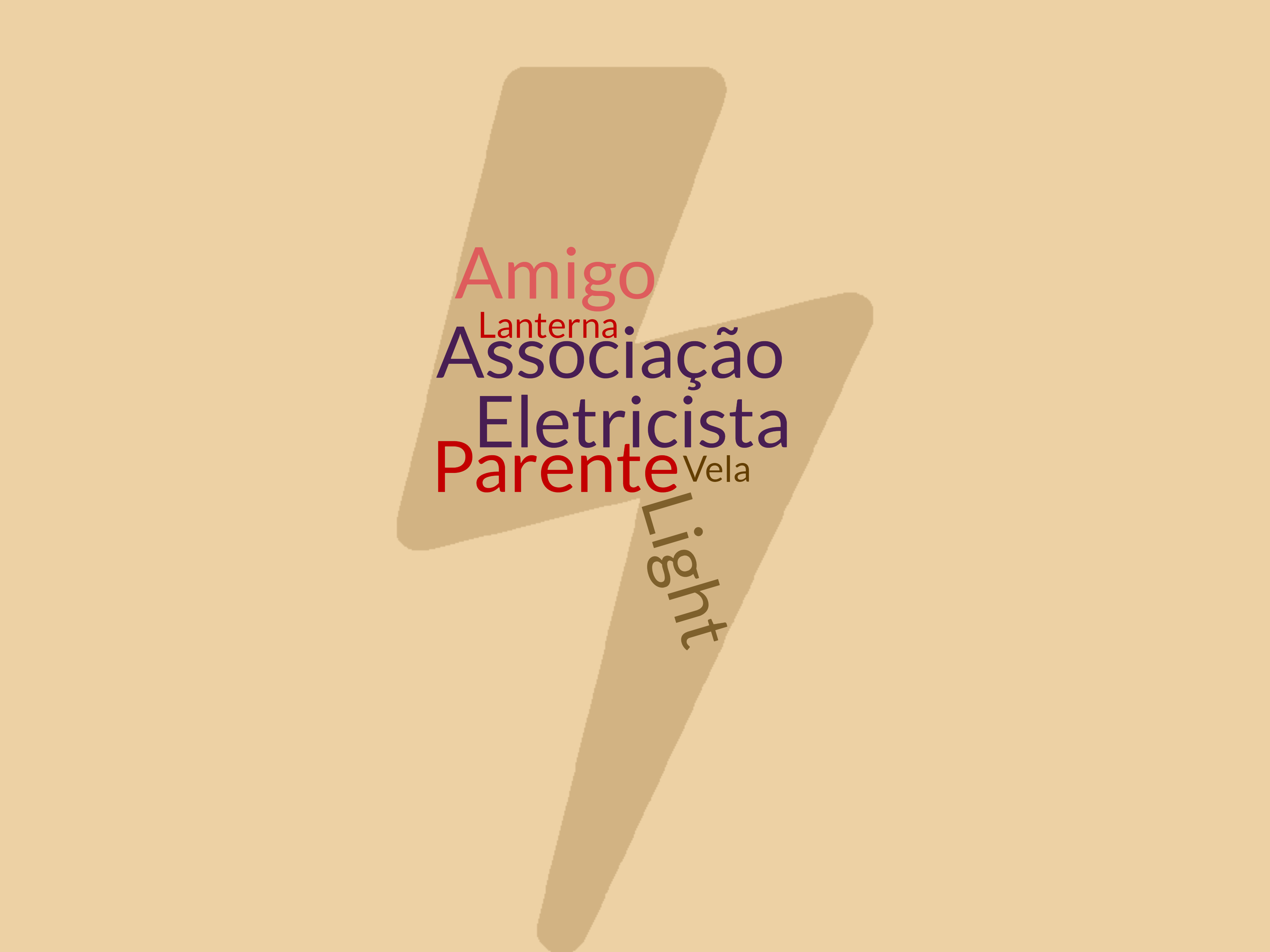

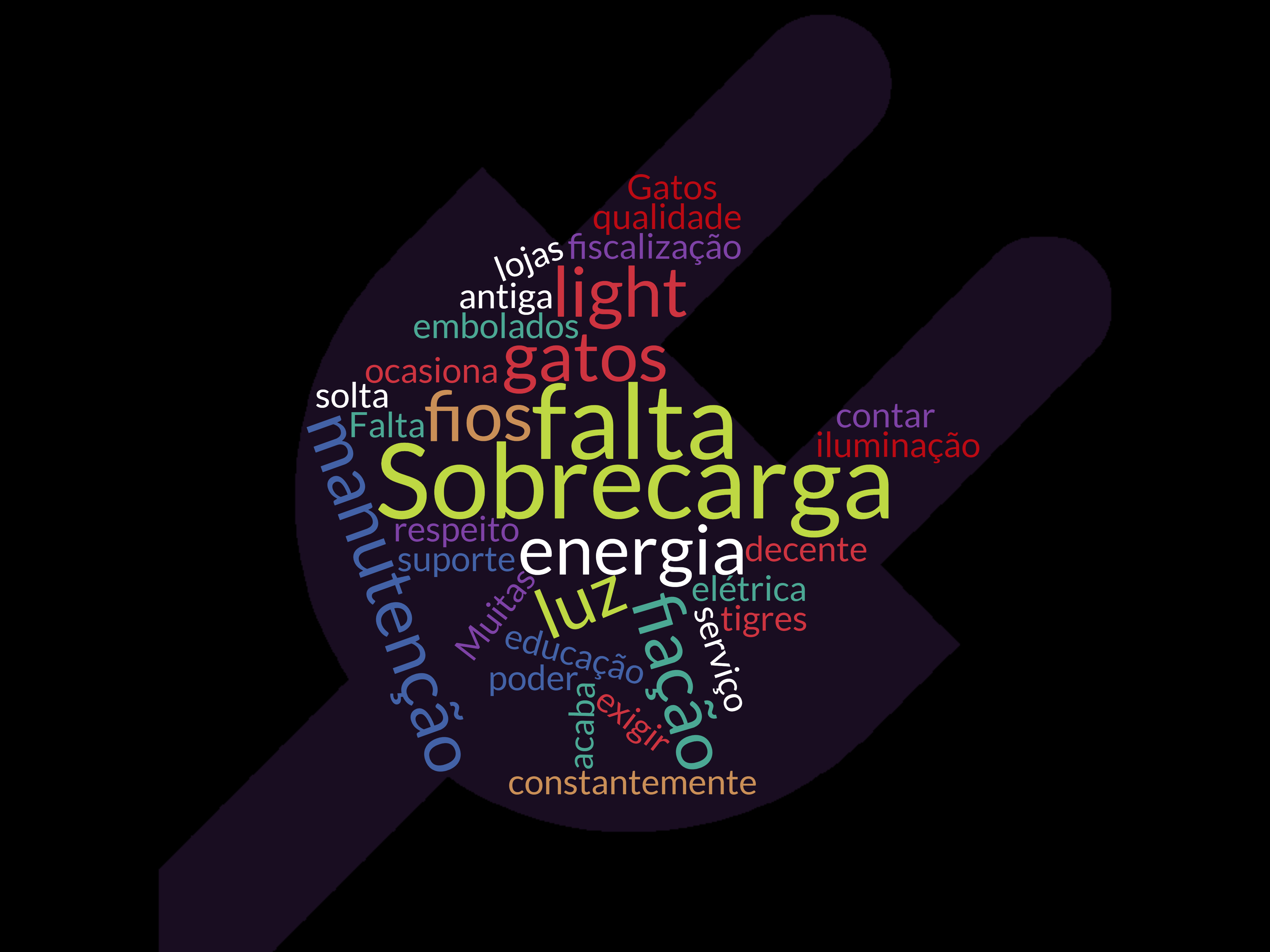

There aren’t that many options when it comes to whom to turn to. We asked residents who they reach out to when there is no electricity in their homes and created the word cloud below with the answers generated. It becomes clear that the support network set up within the community itself—formed by the Residents’ Association, electricians from the favela, and relatives—gets the most mentions; however, this network also denotes the lack of trust in Light and in public authorities to solve potential claims. It is common to see requests for help from the Residents’ Association in community group posts showing snapshots of lampposts on fire. The Association stresses that the lack of maintenance, added to the energy overload creates risk for residents and especially for the favela’s children.

Everything Gets Worse in Summer

Summer is that time of the year for beach, beer and fun, but it also reveals many of the problems Rio has as a city—such as flooding, and landslides caused by rains, and the dreaded blackouts in the favelas. In summer, many people are on break, businesses consume more energy to keep refrigerators, freezers and air conditioners running. Residents also turn on their air conditioners to escape the heat, and this causes overloads in the grid, which is already precarious and ill-maintained. When we asked residents in what period of the year problems with electricity are more frequent, we received 100% identical data: all residents named summer as the time with the most electricity-related problems.

“I’ve lived here for 43 years, there are people who have lived here for 50, 60 years, and it’s always been the same, especially in summer with the power outages that damage our appliances and things,” says Júlio César, a local social worker and creator of JCRÉ Facilitador.

The data presented show the consequences of constant blackouts and long periods without electricity, but the causes of the problem are many and range from the accountability of institutions such as RioLuz [public utility responsible for the city’s public lighting], which fails in the maintenance of wires and lampposts, to the overload of the power grid generated by residents themselves, as shown again in the following word cloud.

The favela we want to see will demand effective measures from the institutions responsible, but also benefit from advertising campaigns focused on raising awareness of residents about certain issues. Thus, it is essential to challenge the stigma that favelas are a place of illegality and disorder, to avoid this segregation, and to see them as part of the city.

But After All, Whose Responsibility Is It?

In the perception of 31.6% of the interviewees, the residents themselves are responsible for the problem caused. There are reports of neighbors who make fresh, illegal connections from original wiring that is already old and damaged; or people who have no understanding of electrical circuits working on grids that take electricity to the homes of hundreds.

“We also hold the government highly accountable for, at the same time that it demands we pay taxes, it does not deliver a decent service for what we are paying. But this is more than just a problem with Light or with the government. It is also a behavioral issue of residents, who need to understand that not wasting electricity is linked to the environmental issue and linked to structural improvements of the favela itself,” declares Júlio César.

But despite the self-criticism of residents in recognizing that they are also part of the problem, mainly by overloading the grid, the institutions that should take care of and deliver a good service fail. 21% of those interviewed believe the government is mostly accountable for supplying bad electricity services to the favela. They report years of State neglect, in which basic needs such as sanitation and electricity have been denied, as the reason for their dissatisfaction.

Another 21% believe that Light is responsible for the poor service. We contacted the company by phone and email but received no response by the closing of this article. The same can be said about RioLuz, which did not respond to our questions until closing.

*The survey was conducted through an online form, respecting all sanitary protocols recommended by the World Health Organization. With this, and due to the number of responses, our ability to generalize to the entire favela is compromised. However, the data presented are fundamental in promoting an important reflection on the degree and impact of energy insecurity in the community and favelas generally, and the urgency to change this scenario.

About the authors:

Bruno Sousa, journalist and researcher, is a co-founder of LabJaca, where he is communications coordinator and researcher. He is currently involved in research on facial recognition applied to public security in Brazil at CESeC. Bruno collaborates for media outlets such as UOL, The Intercept Brasil and Huffpost.

Thiago Nascimento, 23, is a law student at UERJ, an assistant coordinator at IBCCRIM – Rio, an entrepreneur through Reciclar Design, manager of Jacaré Basquete and the creator of the Jaca Against Corona Campaign. She works with public relations and communications at LabJaca.

About the artist: Natalia de Souza Flores, born and raised in Rio’s North Zone, is a member of the Brabas Crew. With a degree in Graphic Design from Unigranrio in 2017, she has worked as a designer since 2015. She launched a magazine of collective comics called ‘Tá no Gibi’ in 2017 at the Rio Book Biennial. Her main themes are based in African culture, using cyberpunk, wicca and indigenous elements.

This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.