This is the third article in a five-part series, published in Portuguese by favela-based online magazine Favela em Pauta and titled “Brazils: Stories of the Periphery in the Pandemic.” Each essay comes from a different region of Brazil; this one from the nation’s Southeast. For the original article by Lia Soares click here. It is also our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on favelas.

What stories do the peripheries tell about the pandemic and inequality? This is the question we wanted to answer when we invited five journalists—residents of peripheries in each of Brazil’s five regions—to participate in this project. The idea emerged from the Coronavirus in the Peripheries Map, an initiative of the Marielle Franco Institute which registered more than 540 collectives that act on the frontlines against Covid-19, in favelas and peripheries across the country. Engaging with the data and stories of these collectives and what they have witnessed, the visions of these five journalists show that it is possible to understand the simultaneous similarities and differences of living in the different Brazils that make up Brazil.

Obstacles to Everyday Life in the Peripheries

“Look, there’s nobody on the streets, I didn’t see anyone at the butcher’s, there’s nobody there to leave behind.

Look, there’s nobody in the square, all there is, is this dull sun,

there’s nobody there to see and to tell.”

— Lyrics to Elza Soares’s Luz Vermelha

Looking back at the first weeks of March 2020, I can remember all this talk about the speed with which a virus we were not really sure the origin of was spreading, or what it might mean for our lives. The first pieces of information that reached us, brought along an extra dose of fear for everyone worldwide, but especially for people living in peripheral zones, who already knew the damage caused by the absence of the State.

Beyond a routine of constant fear, beyond the point of view of traditional media outlets, or even politicians, a panorama became clear that pointed to the veiled stigmas still present in the daily lives of favelas. None of this made any of them take responsibility for their neglect in addressing the problems inherited from previous administrations. None of this changed the fact that the State does not “want” to look at these areas, leading us to understand that even if the whole idea of isolation was presented to this part of peripheral society, that would not exactly be any news.

In the context of a health crisis, the existing problems of lack of basic sanitation and access to water in peripheral areas are certainly likely to contribute to increased numbers of Covid-19 infections and fatalities. Unfortunately, this was what happened, but was mitigated in part thanks to the wisdom and empathy of those who worked to protect the lives of others who were part of their daily lives. Through this realized potential among neighbors, and with support of social movements and organizations working together with favelas, diverse networks were reached and partners businesses were able to provide financial support, with the aim of reducing harm caused by the pandemic.

Upon learning what Covid-19 was all about, I remember writing an early article on the pandemic’s impact on favelas, where I spoke about the promises that the mayor of Rio was starting to make. These promises proved the irresponsibility of the administration, which was never concerned with fighting the real sanitation problems in these regions. A good example was the promise to install hygiene stations with clean water and soap with the aim of reducing the spread of the new coronavirus—a promise that, at the time this article was being written, had not been met.

In Complexo do Alemão, people began to worry when traditional media started talking about the severity of the pandemic. Community organizers went in search of information, trying to understand the level of risk to which the population was exposed. “We went looking for information and found out that the virus was really very dangerous, and our biggest fear came from the knowledge that, living in favelas, our reality is very different from the rest of the country. When you look at a favela, you see people living close together, between alleyways and narrow streets where everything is extremely close,” says Rene Silva, 26, director of independent community newspaper Voz das Comunidades (Voice of the Communities). Living in a favela, experiencing day-to-day life in the peripheries, clearly showed how different this reality is to the national context, further aggravated by a pandemic that required social distancing and, later, legally enforced isolation rules.

Staying home was a privilege afforded once a year to those who work in the formal economy. At first, the requirement to stay home was seen as a period of “vacation outside of vacation time,” and people had a natural desire to go back to work after the first 15 days were over. Once they were fully aware of the real risks of the pandemic, local organizations Voz das Comunidades, Coletivo Papo Reto (Straight Talk Collective) and Mulheres em Ação (Women in Action) had the idea to create a crisis center in Complexo do Alemão to reduce the impacts of the new coronavirus as much as possible.

“When we started to talk about the #StayAtHome campaign, we got lots of messages from residents asking how they were going to stay home if they didn’t have anything to eat. People were saying ‘I’ve got to work; I’ve got to go out and make money for food.’ We know that many people in favelas are self-employed. Some work as street vendors, some sell snacks on the beach. So, for that reason, we were really worried about how we were going to raise awareness to get people to stay home when they needed to go out to work. We started campaigns to get donations, which at first weren’t food drives since we were worried about getting water and hygiene supplies to people because many couldn’t afford it. And during the pandemic, water shortages seemed to get worse, because we already have a chronic water shortage problem in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.”

—Rene Silva, Complexo do Alemão Crisis Center

In total, over 50,000 people were supported by the Complexo do Alemão Crisis Center. 15,000 families received basic foodstuffs, plus hygiene and cleaning products. One positive aspect of the crisis was that the young leader, who once again showed concern for his favela, saw that the whole world was joining the efforts made by these local organizations. Silva said that [during that early time] the organizations had no trouble raising funds, as donations immediately started to be made by people from several countries, as well as thanks to several companies taking action to support favelas.”

Having Faith ‘Cause You’re a Hostage to Fear

My father, who is a resident of Complexo do Alemão, a dark-skinned, middle-aged black man originally from the Northeastern state of Pernambuco, came to Rio de Janeiro in the early 2000s. I dare say that my drive and admiration for the idea of work comes mostly from my personal observations of my dad. He has never been late, he has never missed a day of work (except when he had to undergo surgery, though he was still upset about staying home) and has never complained about the opportunities he received. The thought of not showing up at his place of employment did not sit well with this type who learned that “work makes a man.” I am certain that this relationship with work or, rather, this “tradition” of not just puttering around the house comes from a brand of ancestry that exceeds determination, that is also inherited from the fear of unemployment.

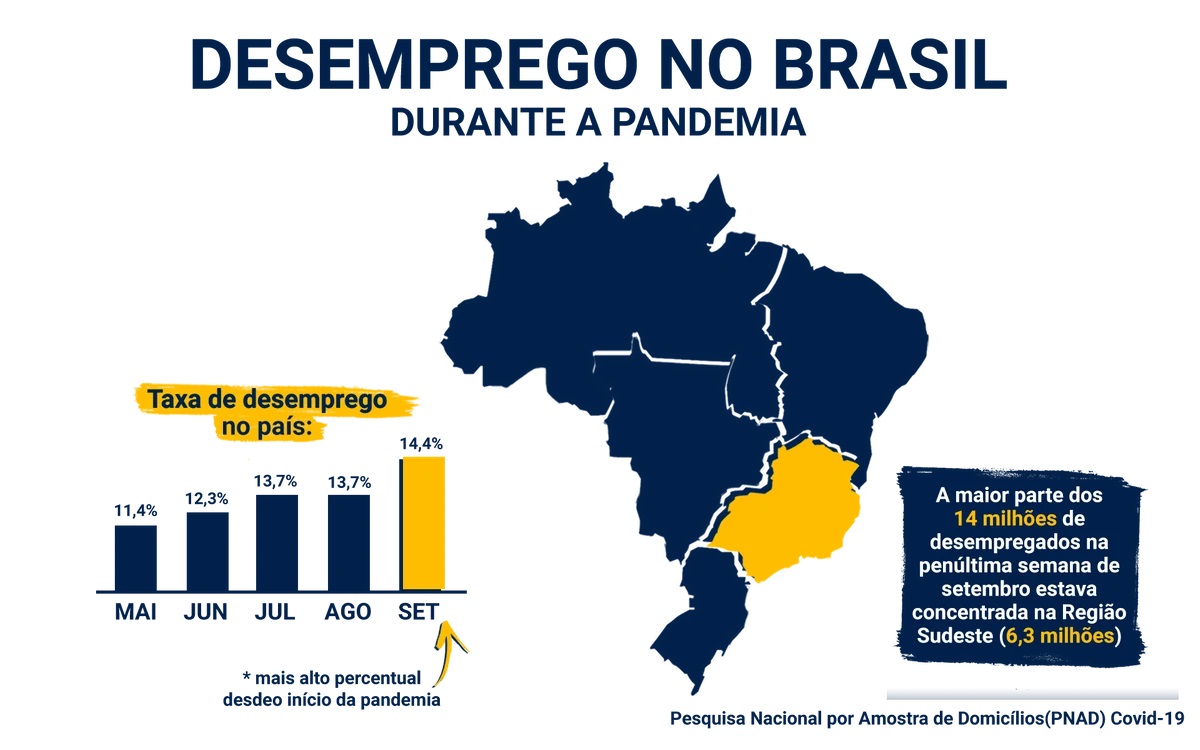

My father is certainly not alone in this fear. According to data shared on October 23, 2020 by the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD), during the Covid-19 pandemic, in the month of September alone, the unemployment rate rose to 14% of the population. Carried out by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the PNAD study revealed an even more frightening statistic: that the majority of the 14 million unemployed lived in Brazil’s most populous region, the Southeast. Its 6.3 million unemployed people represented 39.2% of the country’s total.*

The Concept of Periphery is Very Wide-Ranging and Exceeds Spatial Geography

Data showing the high rate of unemployment in the country certainly had an effect on the mental health of Brazilians who were starting to see the impacts of the pandemic more clearly. Transsexual women, bodies diverse in their sexuality and gender, suffer daily with having their bodies isolated, erased and excluded.

In São Paulo, Casa1, a non-profit that works with LGBTQIA+ people started to focus on guaranteeing the mental health of its beneficiaries. According to Iran Justi, 31, who works in public relations, Casa1’s work in providing shelter had to be paused during the pandemic due to the need to avoid gatherings in enclosed spaces. “Luckily, we realized that some of the people who were staying with us, whether it was thanks to getting access to the government’s emergency aid or to finding a formal job, managed to move out into safer spaces during Covid-19,” he says.

Given that Casa1 had to stop providing shelter to homeless LGBTQIA+ during the pandemic, the organization prioritized giving continued assistance to its beneficiaries, maintaining a social clinic with approximately 55 healthcare professionals to meet the needs of its public. Besides, more than 900 basic foodstuff parcels were handed out to current and former participants of courses offered by Casa1.

“We established a closer contact with the residents we provided shelter for, like in the case of the trans girls who needed support with issues to do with transitioning and self-esteem, besides a whole effort to contain the growing violence that these bodies have suffered and still suffer. This work is done by a team that includes occupational therapists, psychiatrists and psychologists,” says Justi.

The federal government started to develop a plan to provide financial assistance to the population, which represented a brief moment of security for those who had no income. However, the hope of having the emergency aid approved took a while to materialize, and the traditional assumption that “NGOs should do the work that the State doesn’t do” continues to prevail.

For This Bread We Eat

Social inequality in Brazil is a reality that brings to the surface all the scars that colonization and slavery have left on our society. The lack of interest from people in power, and the endless attempts to erase the responsibility of whites who changed the fates of whole continents and lives, are still defended tooth and nail. And hunger is one of the wounds that is still visible. According to IBGE, in the last five years, the number of Brazilians who do not have regular access to basic nutrition has reached 3 million. This reality, added to the current sanitary crisis, which is global in scale, directly affects our economy besides our health.

In Belo Horizonte, a task force was organized so that the work that was already being done to combat hunger in the city’s largest favela could be strengthened during the pandemic. The Humanitarian Front, created by a range of collective organizations and institutions in the Aglomerado da Serra favela, urgently prioritized reducing hunger during the pandemic, according to Danielly Mendes, 26, MBA and project coordinator.

“Since before the pandemic, our residents’ association has worked and provided monthly support to a few families who live in Aglomerado by delivering foodstuffs to them. When the pandemic hit, around March 20, we got really worried because we were getting lots of requests for help and had no way of meeting them. Then we started to ask our partners for help, mainly to provide basic foodstuffs. But we realized that people didn’t just need foodstuffs; we had to provide them with pre-cooked meals because many of those who were asking for help were either bedridden or didn’t have the facilities to make food. So, right from the start, we had to put together an improvised kitchen in order to deliver around 35 meals a day to people who didn’t have the means to prepare their own food.”

As unemployment soared, a large number of these people lost their main sources of income. As a result, requests for support in Aglomerado da Serra quickly increased and, over the course of only a couple of weeks, a database with over 6,000 families showed that most were in need of foodstuffs and/or meal deliveries.

“Talking about social distancing in a favela can be a bit redundant. People live close together, mostly because they live in small houses, one house on top of another. So, it’s difficult to raise awareness among the population that the virus is real, that if it gets into the community, it’s going to be cruel since we never had good access to health services in the first place. The counterargument is also valid since, ultimately, society and the State are not worried about people who live in favelas. They live in tight accommodations in order to work in essential services, and odd jobs that provide them with an income. At the Humanitarian Front, we produced around 60,000 face masks through the Favelinha project, and distributed them along with the foodstuffs and meal deliveries. We also received donations of hand sanitizers, hygiene kits and other items that we used as tools to help us raise awareness,” Danielly recalls.

Over the course of three months, the Humanitarian Front project—which joins the efforts of local organizations ACM Cafezal, Lá da Favelinha and Instituto Unibanco—managed to distribute 18,000 basic foodstuffs parcels, 18,000 hygiene kits, 60,000 face masks, and 168,000 meals for people living in Aglomerado da Serra, in the absence of State support.

The Knot Always Tightens

The romanticization of racial miscegenation in our country has served to make inequality an even more permanent part of our daily reality. The narratives are divisive. After all, what does it mean to be peripheral? The periphery is the result of acknowledging an exclusion that goes beyond geographical issues. It moves through the city every day, in multiple forms. Black people suffer multiple forms of racism that white society fights hard to maintain and perpetuate. The bodies of trans people and transvestites suffer the constant race to survive, trying to at least make themselves seen, and have guaranteed the right to a dignified life. The poorest suffer with a system that deceives them: where their labor would guarantee the utopia of leisure and rest, which until recently was called retirement.

Corruption cases during the purchase of equipment and respirators for the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) forced news programs to put aside bulletins on new Covid-19 cases to tell a story people already know by heart. Lack of information and clarity about the risks of the virus seemed to become a crucial task for the government, that ignores the power of science. Historically, our health services are undergoing a dismantling, and are even under greater risk when we speak about the privatization that seeks to make access to health services a privilege of the elites. That is what puts us all on the same page.

This is the third article in a five-part series titled “Brazils: Stories of the Periphery in the Pandemic.”

*Original article in Portuguese published in February 2021.