This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) is not a topic you hear being discussed in Brazilian school corridors, especially in relation to girls. There is a considerable gap between the sciences and the female universe. Young women are not incentivized to think about science, or to be scientists. This happens in such a systematic way that it seems intentional when in reality it is a structural problem. Unconsciously or consciously, some spaces are designed to lack the presence of women. In mathematics, male dominance in the field is undeniable.

Amongst some professions, particularly those connected to the social sciences and health, we notice a significant recent change in terms of gender. In these professions, we find a very large number of women. It is possible to consider that even in the academic professions there are some destined for women, and this has increasingly become a rule. Exceptions are rare.

Hilda da Silva Gomes, 59, is a biologist and educator at the Museum of Life, and works for Brazil’s national health foundation, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz). Hilda and two other educators, all women, carry out projects targeting young people living in the periphery of Rio de Janeiro: the Pró-Cultural introductory program to cultural production, and Black Girls in Science, which uses scientific outreach as a strategy to promote health, citizenship and empowerment. They aim to eliminate the structural gap that exists between black youth and science.

At school, these girls are unlikely to be encouraged to look at science as a career, which makes it essential to go beyond school walls to encourage and guide black girls towards science.

Thayná Rodrigues, 23, a medical student from the Pavão-Pavãozinho favela in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone, says that her interest in science started at school. She recalls being interested in science in grade school. She spoke eagerly about her curiosity to find out more about living beings, animals and forests. She was still a child when she first became interested in marine biology.

Thayná eventually swapped biology for medicine. She says that science was her greatest discovery: “I saw marine biology as something curious, something that could bring me something new, a way to continuously find out about the unknown. Whenever I learned something, I could see that there was always something else to learn. I think that’s good, it’s what makes science intriguing. Even though we think we know everything, we always have more to learn,” described Thayná.

Thayná eventually swapped biology for medicine. She says that science was her greatest discovery: “I saw marine biology as something curious, something that could bring me something new, a way to continuously find out about the unknown. Whenever I learned something, I could see that there was always something else to learn. I think that’s good, it’s what makes science intriguing. Even though we think we know everything, we always have more to learn,” described Thayná.

Hilda Gomes is from a different generation, but had similar dreams and desires. She grew up in the countryside, surrounded by trees and animals, and said that her interest in science also sprang from curiosity: starting with following a trail of ants, then discovering the joys of trying fruits from different trees, then looking at rainbows and smelling the scent of rain falling on wet earth.

But this is not the reality for most girls who might otherwise choose to pursue a science education. Many of them do not realize the basic right to childhood.

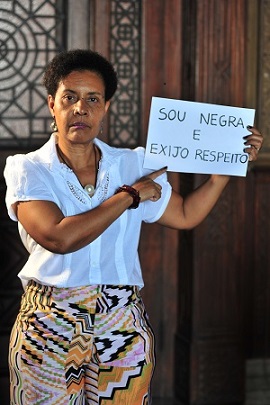

When we consider this from the perspective of race, the situation is even more critical. It begs the question: can black girls be scientists? Is there space for black women in science? Structural racism does not allow black girls to dream. Even when they dream, they are quickly reminded that they are not allowed to keep on dreaming. The reality for these girls is that “they shouldn’t waste their time with that kind of thing,” and the space that could be taken up by science is instead occupied by frustration.

Generally, seeing themselves under pressure to find a job and bring home a salary, young black women are motivated to take short courses that prepare them quickly for the job market. In this scenario, the possibilities for them to get into STEM education, requiring years of cumulative studies, are reduced, reinforcing the idea that women cannot work in areas that are “made for men.” They are pushed, in some way, to find professions that are connected to areas that are seen as feminine: teachers, nurses, carers of elderly people and children, or domestic workers.

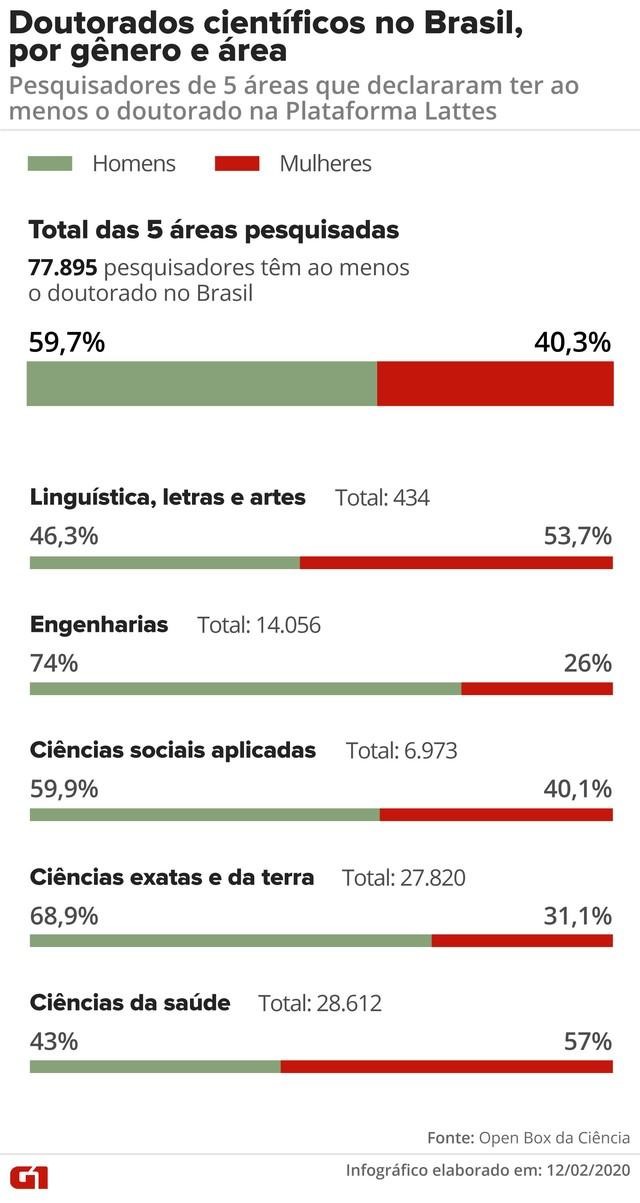

Recently, the G1 news site shared a study that reveals the predominance of male researchers in Brazil. The study showed that there are 31,394 female researchers with PhDs in the five main fields of study in Brazil, a little more than 40% of the total number of PhDs in those fields. Despite their being a minority, there are a significant number of female researchers, especially given the current context of federal funding cuts for scientific research, which have been disincentivizing young people from pursuing STEM education and openly displaying machismo.

Still, according to the article, data from the Lattes Platform showed the real disparity between men and women. The Lattes Platform is an academic CV database where students and researchers from a range of areas can show their academic trajectory and accomplishments in a virtual space. On the platform, scientists gain visibility by sharing research they have conducted on their own or in groups.

In total, in Brazil, there are 77,895 researchers working in the five main areas of knowledge who are at PhD level. Of these, 59.69% are male and 40.31% are female. Given that women make up 51.8% of the Brazilian population and men make up 48.2%, the discrepancy found is significant and disproportionate in relation to the population. Also according to data from Open Box da Ciência, while men dominate the areas of exact sciences (68.9%) and engineering (74%), women are in the majority in health sciences, reaching almost 60%.

As well as the lack of women in some areas of science, women are also affected by the salary difference between men and women: on average, Brazilian women earn 77% of the amount earned by Brazilian men. And, even with a significant number of women occupying roles in health departments, women still earn less than men working in the same roles. It is the same for women in many other roles and professions, within and outside of science. Structural misogyny determines the spaces women occupy, the salaries they earn and the places they have access to. And racism is also at play. Therefore, for black women, getting into the labor market is even harder.

The film Hidden Figures shows the journey of black women in a space that was not intended for them. In the 1960s, during the Cold War and amidst racial segregation policies in the US, three black women were part of the team responsible for the first Moon landing. They had to work hard to show they were experts in their fields and prove the excellence of their academic credentials constantly. How many black women have had to go through this to earn the respect they deserve?

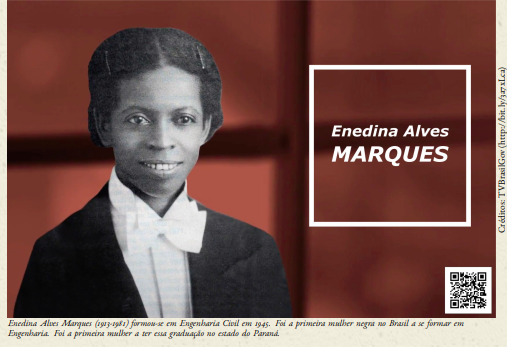

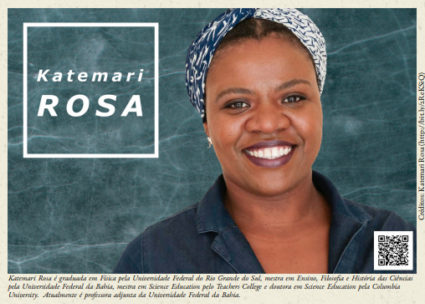

In 2020, under the supervision of Hilda Gomes, Joselí Maria Silva dos Santos created a scientific outreach calendar called Black Women Scientists. The calendar features names such as Enedina Alves Marques (1913-1981), the first black woman to graduate in civil engineering in Brazil; Katemari Rosa, physicist and teacher at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA); Nedir do Espírito Santo, a mathematician who graduated from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF); Sônia Guimarães, physicist and professor at the Technological Aeronautical Institute (ITA); Joana D’Arc Félix de Souza, chemist, instructor and researcher at the Carmelino Correa Jr Technical School in Franca, interior of the state of São Paulo, among others.

When Viola Davis won the prize for best female actor at the Emmy Awards, she cited Harriet Tubman (1822-1913) in her speech: “The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity.” Even though female scientists are fewer in number than men, female scientists, and black female scientists in particular, do exist.

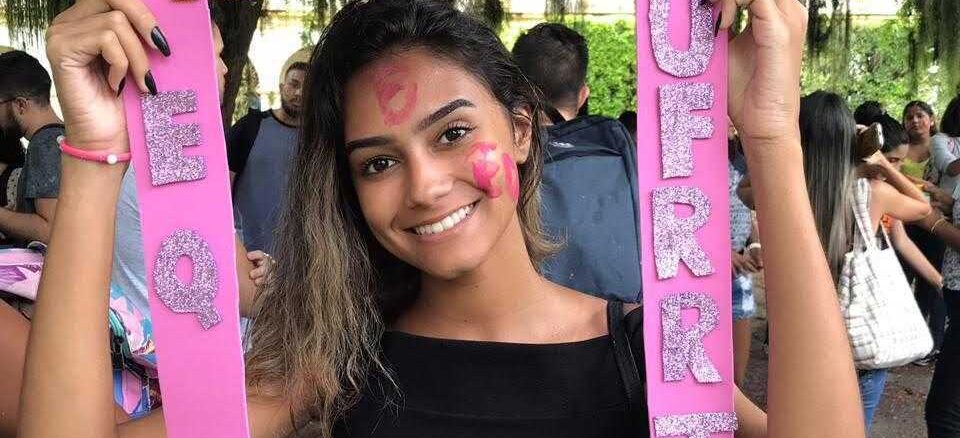

Giovanna Barbosa da Cunha, 19, is a chemical engineering student at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFFRJ), and believes that if she concentrates on her studies, she can reach places that had been unimaginable for a black woman, and that through her achievements she can become a role model for other black girls, showing what they too are capable of. Showing them that science is also their place.

Giovanna and Thayná’s belief, and the belief of many other girls and women, that women, too, can be scientists, is increasingly confirmed. Last year, with the threat of coronavirus looming, Brazilians learned about Jaqueline Goes de Jesus, 31, a young black biomedical scientist from the state of Bahia who was part of the University of São Paulo (USP) School of Medicine‘s team of researchers responsible for sequencing the genetic structure of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This was done in only 48 hours, after confirmation of the first case of coronavirus in Brazil. Besides Jaqueline, who we learned about during the pandemic, how many Hildas, Thaynás, Joselís, Enedinas, Katemaris, Nedirs, Sônias, Joanas, Giovannas and other Jaquelines are working as scientists, waiting for opportunities to come their way? More and more, science has to become “something women do.”

About the author: A native of Rio and a resident of the city’s North Zone, Cynthia Rachel Pereira Lima is working on her master’s in African Literature at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). Cynthia created the group @encruzilhadafeminina (Feminine Crossroads) focusing on Black Art. She writes and directs plays, having created the @pretonopalco (black on stage) project, which focuses on black theatre. She is a volunteer literature teacher at the Institute of Human Teaching and Popular Education (IFHEP).

About the artist: Raquel Batista is a visual artist who works as a photographer and illustrator. A black woman, resident of Rio’s West Zone, she is an undergraduate at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s (UFRJ) School of Fine Arts. Her goal is to use art to represent people who, like her, a young black woman from the periphery, are not always seen.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.