The strong rains that hit the state of Rio de Janeiro in early December caused floods in several cities. The consequences of the storm were shown on several news outlets. In the municipality of Itaguaí, in greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, water invaded homes and sewage returned through drains. After intense media coverage of the storm, the municipality of Itaguaí sent machines and employees to the neighborhood of Engenho, one of the most affected locations. Instead of help, however, residents had their losses amplified. Some houses were demolished without prior notice and others received notification for demolition.

It was nighttime when the home of 61-year-old Vicente da Silva started to be demolished. The notification arrived along with the bulldozers, at approximately 11pm on Thursday, December 9. “They handed him the notification and wanted to tear everything down right away. My father, desperate and not knowing what to do, gave them my number so they could call me,” says Daniel Ferreira da Silva, his son. On the phone, a Department of Social Services employee told Daniel that his father’s house was the reason for the flooding in the neighborhood. “They [City Hall officials] put a lot of pressure on us, destroyed half his house, then threw all the rubble in a ditch. So, in the end, it didn’t do any good,” explains Daniel.

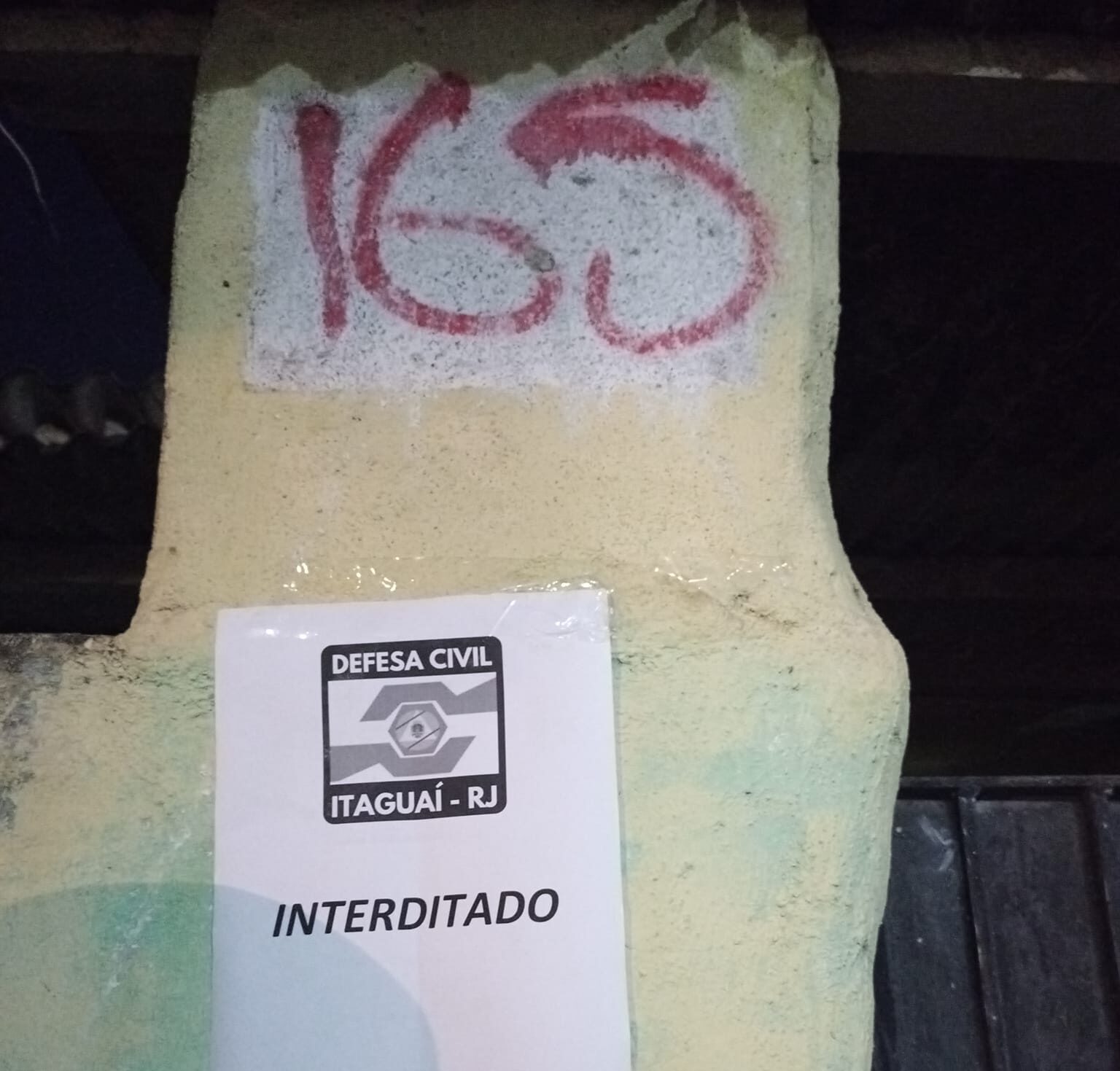

Vicente lived in his house for over 35 years. His son says that the property was considered legal for many years and his father even payed property taxes. In the part of the house that was demolished, there had been a porch, kitchen and bathroom. Officials told the elderly man that the demolition would be partial, but asked him to sign a document mentioning that access to the building would be shut off. Daniel says that neither he nor his father signed the papers.

The elderly man’s house was not the only one to be demolished. At least six properties were torn down and others were notified that they would soon be demolished. Anna Paula Salles has lived in the neighborhood for decades and currently presides over the Engenho Residents’ Association (AME). According to her, city officials who were at the site claimed that tearing down the houses was necessary to unblock the canal that cuts through the neighborhood. With the houses that run along the canal demolished, there would be room for them to come in with machinery. “They said they wanted to go over the entire ditch with the machines, but it’s only a small ditch. It’s not wide enough to fit a hydraulic excavator,” explains Salles. In addition, those who live in the neighborhood fear that an intervention with heavy machinery in the canal could affect the structure of nearby houses.

The action carried out in Engenho was described on the municipality of Itaguaí’s website. The text mentions the removal of debris and garbage from the canal and the possible removal of walls, but it does not bring up the demolition of any homes.

After half the property was demolished, Vicente spent a few days with family members. According to Daniel, his father did not receive any offer of assistance from the City. The elderly man heard from employees that the rest of the house would need to be knocked down so that the machinery could access and remove debris. “Afraid of losing the other part of his home, my father removed [the rubble] manually,” said da Silva.

Since then, Vicente has returned to the partially destroyed house. When he needs to use the bathroom, he counts on the help of neighbors. His home no longer has walls to keep it separate from the canal. According to Daniel, he personally sought out the city’s departments of Civil Defense, Public Works and Social Services. “They said that the demand is very high, that there are many houses in the same situation, and that was it.”

A few meters from Vicente’s house is another demolished residence. Everton da Silva Telles, 22, was at work when employees arrived, also on Thursday, December 9. The house was empty at the time, and a neighbor warned him about the demolition. He immediately left work but arrived too late. “Since it’s a long way from Nova Iguaçu to Itaguaí, everything had already been torn down by the time I got there,” he recalls.

He and his mother lived in the property, which had two rooms and was undergoing construction. The land on which the house was built had been in the Telles family for almost 50 years ago. As in Vicente’s case, Telles was offered no social assistance.

The next day, Telles’ mother looked for the accountable agencies, but got no response. Telles himself tried to talk to the officials, who returned to the neighborhood for another day of demolitions and delivery of notifications. “I told them they weren’t coming in. But, on our own, we can’t really go head-to-head with them. They said they were going to call the police, that they were going to arrest me if I didn’t let them on the land,” says Telles. Feeling hopeless, he tried to negotiate by offering to let the machines enter the grounds over the rubble of where the house had stood, and all he wanted in return was for the front wall to be rebuilt. He heard from officials that because the land was illegally occupied, the municipality could enter and demolish what was on it without any obligation of offering compensation to residents.

The rubble from Telles’ house was also left behind on the canal’s banks. Since the day the house was demolished, other rains have flooded the neighborhood. “It rained again on Friday [December 17] and everything there was under water. All their work was in vain. It’s not just about cleaning that one spot, they have to clean the entire ditch. The drainage pipes they put in can’t hold [the volume of the water],” he explains.

The problems with flooding in the area are not recent. According to Anna Paula Salles, the buildings—houses and alleys—that run along the canal, have existed for over 30 years. “Does City Hall suddenly want to solve a 30, 40-year problem in one week? It’s not possible, right? People are desperate,” she says. The president of the residents’ association points out that the basic sanitation structure that serves the community was built at least 30 years ago. The city’s population, as a whole, grew and the network did not keep up: “It’s a problem with lack of basic sanitation: the structure is inadequate and is no longer enough. People who live on the banks of the ditch are aware that they live in a risk zone, but they’ve lived there for 30 years. Where are these families supposed to go?” asks Salles.

Organizing For the Right to Resist

The municipality’s actions in the neighborhood took place between December 9 and 10, following 48 hours of continuous heavy rains that hit Itaguaí. Salles says that the residents mobilized and began recording the violations that were taking place through photos and videos. “We organized ourselves and posted the videos on social media. We managed to call the whole city’s attention. So what did they do? They dialed things down a bit. And that’s when we were able to hold a meeting with all the residents affected.” From that meeting came the decision to file a complaint with the Rio de Janeiro State Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP-RJ).

The meeting was held virtually on Monday, December 20. The community gathered at the residents’ association headquarters to talk with a group of public defenders. “We could tell we had the support of the Public Defenders’ Office,” described Salles. “The community felt embraced and empowered with this meeting.”

Supporting documents and images are still being collected, according to the Public Defenders’ Office. Some documents were requested from the municipality of Itaguaí, represented at the meeting by the municipality’s Attorney General, in addition to the departments of Civil Defense, Public Works and Social Services. “I am personally quite relieved because we are not alone. You can’t just take arbitrary action locking horns with an organized community,” said Salles, hopeful for a resolution of the community’s situation.

The residents’ association representative also pointed out that the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) issued a ruling that prohibits displacements and evictions during the Covid-19 health crisis. The measure mentioned by Anna Paula Salles suspends any orders or measures requiring residents to vacate areas that were already inhabited before March 20, 2020, the day public emergency was declared in Brazil due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The ruling is to be maintained until, at least, March 2022.