This is our latest story on coronavirus and its impacts on favelas.

On the morning of May 28, the Military Police evicted Cleuza Maria de Toledo’s family, who lived in the Penha Brasil Occupation, in the district of Cachoeirinha, in São Paulo’s North Zone. Without a place to live, she depended on family those days after being expelled from the occupation. Like her, approximately 230 other families had to find shelter in the midst of the pandemic, after many lost the means to pay rent, as reported by Folha de São Paulo.

Toledo saw the occupation as a chance to stay housed since she could not find better lodging for herself and her daughters, aged 9 and 19, one of whom has intellectual disabilities. “She is schizophrenic and autistic. I cannot work because I take care of her,” Toledo says.

In April, she already predicted that if the repossession occurred, she would have nowhere to go. At the time, one of her biggest concerns was her daughter’s anxiety over the move. “Her mind gets out of control. She understands the conflict of leaving a home and gets overexcited.”

The repossession was authorized by Judge Paula Fernanda de Souza Vasconcelos Navarro at the request of the landowner, the International Grace of God Church, led by millionaire evangelical pastor R. R. Soares, owner of several Brazilian corporations.

Under threat of eviction, on the eve of removal residents gathered in protest in front of the Court of Justice’s Second Private Law Subsection, located in Sé, in São Paulo’s Central Zone. In addition, the São Paulo Public Defender’s Office requested an injunction be granted against the repossession order. The request was denied on appeal.

In the injunction denial ruling, the case rapporteur, Ricardo Pessoa de Mello Belli, stated that “the delay in complying with the eviction ruling to allow for public authorities to find settlement destinations for the defendants, would have no effect other than to intensify and extend the squat.” For the magistrate, allowing the settlers to stay would only increase the number of squatters.

Community leader at the site, Alexandre Fernandes da Silva, says the number of occupants was largely due to the pandemic, which reduced the income of the poorest. “Families had no financial means to afford their rent and other expenses. The families moved to this land out of need,” he points out.

Overall, Silva says the occupants were low-income, having already been evicted from their homes for not paying rent. Others, unemployed, had been left without the federal government’s emergency aid payments [where had been interrupted for three months].

Following repossession, the families dispersed. Some took shelter in other communities and neighborhoods of the region, such as Barra Funda and Jardim Peri. “Others were stranded on the streets or went to public shelters,” says Silva.

Poor families’ evictions during the pandemic are nothing new. In June of last year, approximately 900 people were removed from a plot of land called Roseira, in Guaianases, in São Paulo’s East Zone.

At the time of publication, neither São Paulo City Hall nor the International Grace of God Church had responded to our requests for comment concerning the evictions.

Evictions in the Country

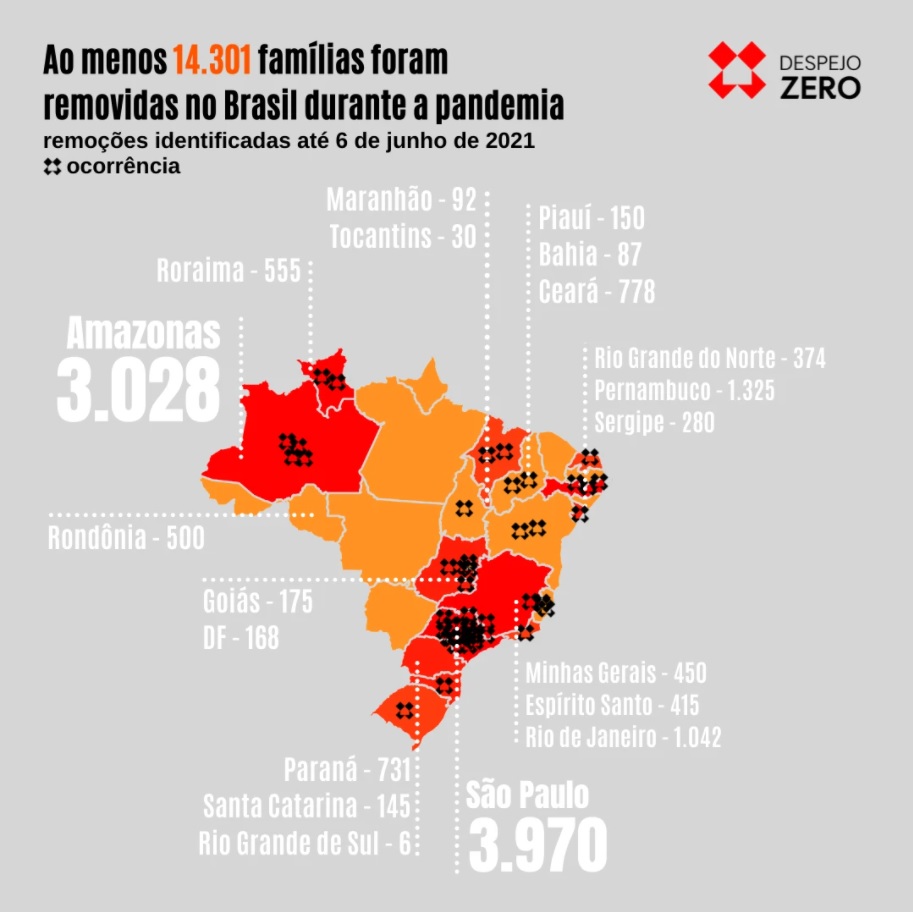

New data from the Zero Evictions Campaign indicate that at least 14,301 families were evicted in the period between March of last year and June 6 of this year, despite the pandemic. Currently, 84,092 families are under threat of eviction in Brazil.

According to the campaign’s organizers, these figures, which are certainly an underestimate, are monitored via complaints and surveys conducted by organized grassroots movements, institutions involved with the theme, as well as state Public Defender’s Offices.

The campaign, launched in June 2020, already within the context of the pandemic, has gained greater capillarity. “Not only because the numbers of threats and of collective evictions continue to rise, but due to their political nature,” says Benedito Roberto Barbosa, or “Dito,” attorney for São Paulo’s Union of Housing Movements and coordinator of the Zero Evictions Campaign.

Data from the campaign show that the national anti-eviction movement contributed directly to the suspension of at least 54 evictions. In effect, 7,356 families were not displaced in the country thanks to injunctions filed due to popular mobilization.

Data from the campaign show that the national anti-eviction movement contributed directly to the suspension of at least 54 evictions. In effect, 7,356 families were not displaced in the country thanks to injunctions filed due to popular mobilization.

On June 3, Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) Judge Luís Roberto Barroso issued a six-month suspension of eviction orders and measures affecting vulnerable individuals who had already moved into their current settlements before March 20, 2020—the day public emergency was declared in Brazil due to the coronavirus pandemic.

This ruling was seen as an important victory by housing grassroots movements. Another bill making its way through the federal Senate that may help displaced families is Proposed Bill 827/2020 prohibiting collective evictions until the end of 2021, including the reversal of all evictions that took effect since March 20, 2020, except for lawsuits already finalized.