This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

In the favelas and peripheries of Brazil, arbitrary arrests—lacking proof and motivated by race, community territory and social class—happen every day. A case study of this nefarious mechanism reflecting Brazil’s structural racism lives in a modest house in the neighborhood of Turiaçu, in Madureira, located in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, where Tiago Marques de Oliveira, 28, needed to prove his innocence after being accused of attempted murder by the State. Even without any evidence of the young man’s alleged involvement in the crime, the Military Police arrested him, and the Civil Police vouched for the arrest, which was not only accepted, but also upheld by the Brazilian justice system. Even in the absence of proof, Oliveira joined the country’s contingent of more than 215,000 pre-trial detainees, and has been living in “hell,” in his own words, since July 31 of this year, after a police operation in Morro do Salgueiro.

“We lose track of time; a day feels like eternity. They [the cops] arrest us based on our skin color and what we’re wearing. Nowadays, I’m not sure I could wear my hoodie or a cap anymore, because I’m scared of being confused with someone else. They said I was involved, and the judge believed them, she didn’t take into account anything I said or the fact that I am a worker with signed papers to prove it.”

Singled Out and Arrested

It was a Saturday, July 31. Oliveira and his father, Ronaldo Marques, took a bus to the Salgueiro favela, also located in Rio’s North Zone, where the boy’s aunt lives. The trip’s purpose was to pick up a basket of basic foodstuffs. Soon after meeting up with family members, Oliveira went to a bar near his aunt’s house, where a party was going on, to meet his cousin. Everyone was suddenly caught off guard by a police raid, which caused fear and confusion, with bombs, gunshots, and shrapnel raining down. Fragments hit the young man’s face. Despite his injury, Oliveira realized his 14-year-old cousin had been shot in the leg. When he tried to assist her, a bomb went off right next to him.

“It all happened very fast, then I helped my cousin and we took her to the hospital in the police car. A few hours later, inside the hospital, I was told that I couldn’t go home, and that I had to go to the police station to give a statement because I was being accused by the officers of having been involved in the shooting. Apparently, they wanted to blame and arrest someone. I’m not sure if they get any kind of bonus for that kind of thing, but that’s the feeling I got at the time.”

Oliveira’s teenage cousin was hospitalized, underwent surgery on her leg and was discharged a few days later. His retired father, Ronaldo, began to experience high blood pressure after his son’s unjustified arrest.

“My father was traumatized. I can’t go anywhere without him panicking; he worries. He always thinks that what happened is going to happen again. Now he needs to undergo all sorts of tests, because his blood pressure is always fluctuating. This has upset our family in many ways.”

Times had been hard enough for Oliveira, who lost his mother six years ago to stomach cancer. Leaving behind his dream of becoming a soccer player to work as a salesman and help support his family, Oliveira considered taking the exam to join the Civil Police of Rio de Janeiro to offer his loved ones a better life. Before being incarcerated, he would wake up early every day and leave home at three in the morning for Barra da Tijuca, where he worked as a stock boy. After his arrest, his employers were so concerned about his fate that they sent his work documentation to the Rio de Janeiro State Court of Justice, which ignored the legal paperwork during his preliminary hearing.

Times had been hard enough for Oliveira, who lost his mother six years ago to stomach cancer. Leaving behind his dream of becoming a soccer player to work as a salesman and help support his family, Oliveira considered taking the exam to join the Civil Police of Rio de Janeiro to offer his loved ones a better life. Before being incarcerated, he would wake up early every day and leave home at three in the morning for Barra da Tijuca, where he worked as a stock boy. After his arrest, his employers were so concerned about his fate that they sent his work documentation to the Rio de Janeiro State Court of Justice, which ignored the legal paperwork during his preliminary hearing.

The racism, humiliation, prejudice, ill-treatment, and verbal abuse endured in places of deprivation of liberty, revealed to Oliveira the reality of the Brazilian prison system. The young man stayed in a tiny cell with over 30 prisoners, one of whom was infected with tuberculosis. “The cell was the size of this bedroom,” he said, using his cell phone camera to show a room holding a single wardrobe and a bunk bed in which he sleeps with his four-year-old son, Miguel. It was specifically the love for his son and the support of his family that motivated Oliveira to keep the faith during his days in jail.

Oliveira had never been in a prison before. After being arrested, in six days, he went through two different ones: Casa de Custódia de Benfica, in the North Zone, and Cadeia Pública Tiago Teles de Castro Domingues, in the city of São Gonçalo, in Greater Rio. Unlike what he had always imagined, and seen on TV, while there Oliveira felt supported precisely by those deprived of their liberty: “I still don’t know what to say, because I was humiliated by the State, which is supposed to protect people. But inside that dreadful place, I felt embraced by the people who were jailed. They told me, ‘My man, you’re going to get out of this. Have faith and believe in yourself. God is just.'” Pain and sorrow come through clearly in Oliveira’s watery gaze. They are the eyes of someone who demands justice and the end of mass incarceration. The young man asks for freedom and justice for people who, like him, have been unjustly deprived of social contact:

“In addition to wanting to prove my innocence, I need to tell you to look after innocent people like me who are inside. There’s a young guy there whose mother has been crying for over a year. He’s innocent and has no way of proving it. I [got out and] came home, but his mother goes there all the time, even tough she is in no condition to do that. I’m shaken by everything I’ve seen.”

The Human Rights Commission and Public Defender’s Office Follow up on the Case

On Saturday, after Oliveira’s arrest, his family got together and raised funds to pay a lawyer to help prove the young man’s innocence. On Sunday, his relatives sought the Human Rights Commission of the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ), and it was thanks to this joining of forces between the family, lawyer, Human Rights Commission, and Public Defender’s Office, that Oliveira was released from jail after six days, and currently awaits, from home, the moment when he will have to answer for a crime he did not commit. Oliveira is especially thankful to the institutions that are dedicated to proving his innocence:

“The commission, the public defenders and the media were essential for my release. Yes, the media was important because it stayed on top of my case. The Human Rights Commission, along with the Public Defender’s Office were pivotal in giving me the greatest chance to get out of that place. If it had been up to the lawyer alone, I think I might have stayed there longer.”

When seeking the Commission’s aid, the family was received by state deputy Dani Monteiro and by Mônica Cunha, an associate of ALERJ’s Human Rights Commission and founder of Movimento Moleque: “When these things happen, families feel lost. We visit favelas and realize these cases take place on a daily basis. That’s why we go to favelas, listen to the residents, and show support.” Monica understands the pain of the families who seek the Commission because, 15 years ago, her son was murdered by the State at the age of 20. Five years before his death, when he was 15, Rafael da Cunha started to fulfill socio-educational measures through a juvenile detention facility (in Rio called the General Department of Socio-Educational Action, or DEGASE). That was where Monica’s struggle began, faced with the various abuses her son and other adolescents were subjected to within the unit:

“Brazil is a racist country and it jails its black and its poor. Oliveira’s case is now being followed by public defender Maria Júlia who, thanks to a collective effort, has filed the necessary documents for the lawsuit. This country’s racist practices make it important that we fight and protect each other. And we understand that the way to fight racism is, in fact, through collective efforts, through human rights institutions. This is the path we have been taking to fight State violations against the Afro-Brazilian, peripheral, poor and favela population.”

The Preliminary Hearing and Mass Incarceration

Oliveira remains at home, awaiting the date of the new hearing that will decide his future. His request for release was denied at his first hearing, held only on the third day after the arrest. The worker’s pleas and his attempts to prove his innocence were in vain, even though there was no evidence against him. “The judge didn’t even look in my eyes. I couldn’t open my mouth to talk. I told her I had my pay stub and my work permit on me but she wouldn’t listen. She only addressed the cops. I was only heard after the lawyer’s arrival, at 1am. Unfortunately, a lot of people held there can’t afford to hire a lawyer.”

Oliveira spent days barefoot on the cold floor since the unit failed to provide him even with the simplest pair of flip-flops. “In the last days, neither I nor almost anyone else could sleep, since there were no beds in that tiny space,” he recalled, verging on tears. Asked if he knew why he was arrested, he went straight to the point: “Because I’m black, because I live in a favela, because if I dress the way I want to I’m immediately seen by the State as ‘bad.’ But all I am is a worker who leaves home at three in the morning to work and afford to buy an outfit that I like, that I think is nice.”

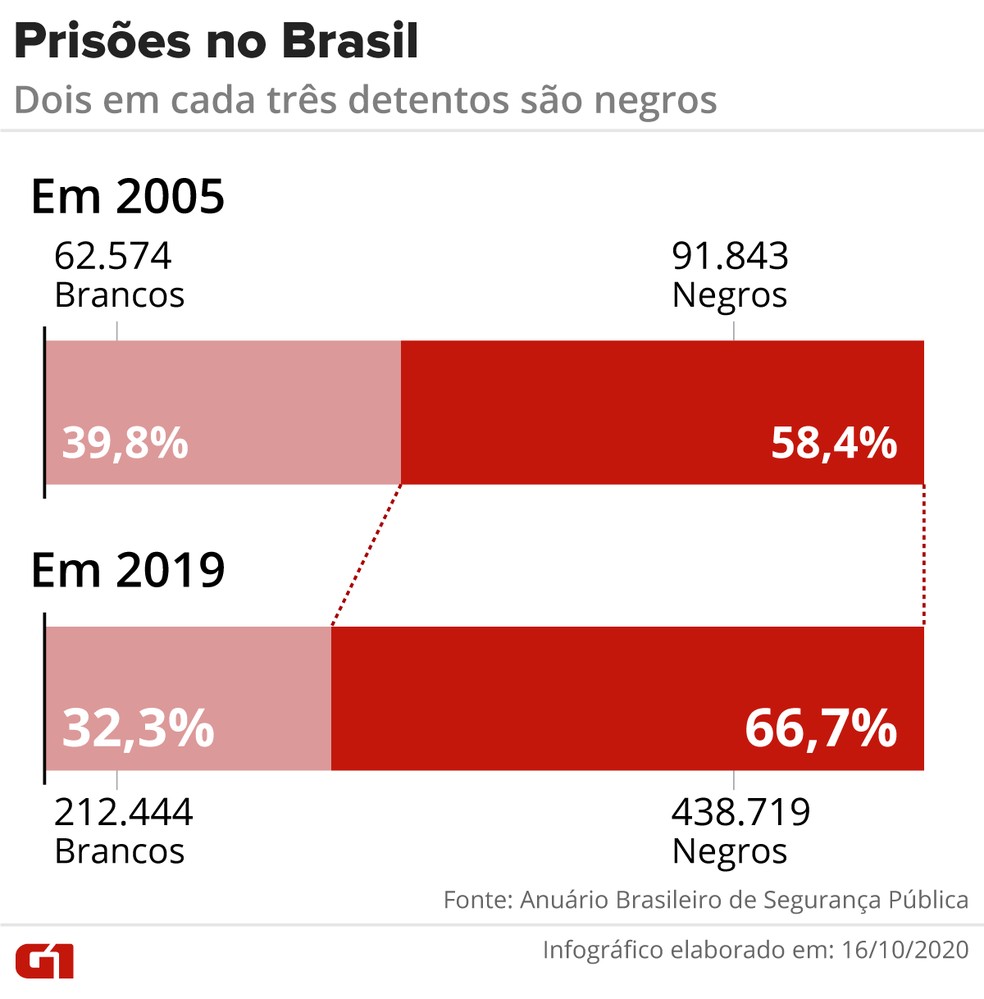

Unfortunately, Oliveira is the portrait of Brazil’s prison population. And the profile of pre-trial detainees is no different to that of most prisoners identified in the Brazilian prison system. The main victims of the system of deprivation of liberty are young Afro-Brazilians (between 18 and 35 years old) who are poor (with either very low or no income at all). These data come from the report “Prison as a rule: the illegalities and challenges of preliminary hearings in Rio de Janeiro,” released in October, 2020 by the Institute for the Defense of the Right to Defense (IDDD), Global Justice and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s National Law School’s Observatory of Preliminary Hearings (OBSAC-UFRJ).

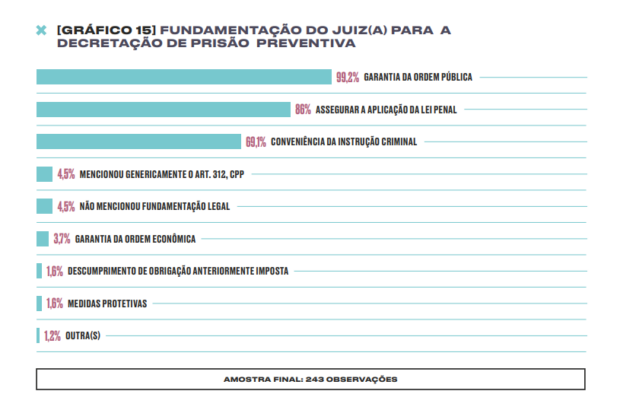

The study also points out that over two-thirds of provisional arrests analyzed in the report involve crimes committed without violence or serious threat, which should not require a deprivation of liberty response. Among the most common justifications given by judges during hearings for provisional detention are “the reassurance of public order” (95%), “ensuring the application of criminal law” (85.5%), and the “convenience of criminal process” (69%), whose purpose is to prevent the accused, for example, from destroying evidence or threatening witnesses. Surpassed only by the USA and China, Brazil has the world’s third-largest prison population, with more than 773,000 people deprived of their liberty.

Oliveira’s trauma is the result of a historical policy of Afro-Brazilian extermination, which has demanded, since the abolition of slavery, that the black population prove that they are duly employed, that they pay taxes, and that they are neither vagrants nor homeless in order not to die or be arrested. Sometimes, not even this evidence is sufficient to prove the innocence of black men, who are still convicted and imprisoned. Black men have been taught since childhood to always carry their identification papers, even if all they are doing is crossing the street to go to the bakery across from their homes. Many have heard their mothers say, “Boy, take your ID in case the police stop you. Take your ID so they don’t think you’re a thief.”

Monique Cruz, a researcher at Global Justice, a human rights organization that denounces State violations on topics such as public security and criminal justice, explains that in “many cases [that] occur in favelas, individuals will be singled out as drug dealers or persons associated with the drug traffic simply because they live or were arrested in a particular region.”

Racism configures social norms in Brazil, and it is no different in the penal system or in prisons. Elaine Paixão, coordinator for the National Agenda for Decarceration, unveils the percentage of black individuals deprived of liberty in Salvador, Bahia: “Currently, 93.40% of the prison population in the capital of Bahia is comprised of black people. In Bahia, the black population is 79%! In other words, when the armed wing of the State approaches the black population, it either kills or arrests.” Paixão then concludes:

“We, who are family members, know that the State kills inside when it doesn’t kill out here. Those who are incarcerated are ripe to catch all kinds of illnesses. The number of cases of tuberculosis is very high. The State underreports the cases, but we find relatives of people deprived of liberty who always report that all sorts of issues aren’t reported anywhere. The prison system is unhealthy!”

About the author: A graduate of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), journalist Camila Fiuza is the product of public schools and a member of the Northeastern chapter of the Mothers of May. A black, peripheral woman who fights for human rights and against racism, she has contributed to community radios and worked for Record TV Itapuã and Band News FM Radio, in Salvador.

About the artist: Illustrator Yara Santos is a student of generalist design at the University of São Paulo (USP). Born and raised in the periphery of São Paulo, she seeks to represent elements of the black and peripheral culture in which she is inserted in her art. Most of her production is centered on digital techniques.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.