This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

On International Museum Day 2021, the Sustainable Favela Network‘s (SFN)* Memory and Culture Working Group organized an online event entitled “Favelas, Memories and the Pandemic: A Guide to Our Experiences.” The goal was to present the Guide to Museums and Memories, to take a tour of museums that are part of the Guide, and to debate memory in the pandemic.

The event was attended by community leaders and allies who work to preserve the collective memory of favelas: Maria da Penha, resident of Vila Autódromo and representative of the Evictions Museum; Lourenço Cezar da Silva, teacher and director of the Maré Museum/CEASM; Emerson de Souza, musician, social activist and representative of the Horto Museum; and Adilson Almeida, president and director of the Camorim Quilombo Cultural Association (ACUQCA).

The event was attended by community leaders and allies who work to preserve the collective memory of favelas: Maria da Penha, resident of Vila Autódromo and representative of the Evictions Museum; Lourenço Cezar da Silva, teacher and director of the Maré Museum/CEASM; Emerson de Souza, musician, social activist and representative of the Horto Museum; and Adilson Almeida, president and director of the Camorim Quilombo Cultural Association (ACUQCA).

Moderated by Beatriz Carvalho (from Mulheres de Frente), with the participation of Luiza de Andrade (Evictions Museum) and Igor Valamiel (facilitator of the SFN’s Memory and Culture Working Group), the four presenters spoke to 250 people, between a Zoom and Facebook Live audience.

“Much has already been lost of the memories and the history of communities, favelas, ghettos, and peripheries,” said Maria da Penha, as she introduced the Guide.

“Brazil did not show the due care and attention in preserving, in full, the memory of its indigenous people, of its black and poor populations, who have always contributed to building and developing this country.”

The Guide to Museums and Memories

The recently released Guide to Museums and Memories is an initiative of the Sustainable Favela Network’s Memory and Culture Working Group. “The Guide was first conceived before the pandemic began, with the goal of providing easily available information to those who wanted to know and visit the museums,” said Luiza de Andrade, who helped put together the social museology project. “Despite the pandemic, we put this Guide into practice over the past year. It starts with a preface, followed by the presentation of the projects, with a total of 26, listed from oldest to newest. Then we have a map showing the location of each museum. And, finally, we have texts on the themes covered by each.”

The recently released Guide to Museums and Memories is an initiative of the Sustainable Favela Network’s Memory and Culture Working Group. “The Guide was first conceived before the pandemic began, with the goal of providing easily available information to those who wanted to know and visit the museums,” said Luiza de Andrade, who helped put together the social museology project. “Despite the pandemic, we put this Guide into practice over the past year. It starts with a preface, followed by the presentation of the projects, with a total of 26, listed from oldest to newest. Then we have a map showing the location of each museum. And, finally, we have texts on the themes covered by each.”

The intention was to put together a clear guide. “We wanted it to be easy to read and helpful for users to get in contact,” Luiza explained. “This could also be an interesting tool in the classroom, especially in public schools, for students to learn more about these museums, to know that they exist within their communities, that they are not far from their own realities. This Guide is also important for the museums themselves to get to know each other better.”

The historical and cultural impact of the Guide cannot be ignored, since it sheds light on projects that rescue the identity of the population, projects constantly being undervalued by society. “This publication seeks to show the riches and knowledge developed over the years by projects that value the memory of Rio’s favelas, quilombos, and peripheries; projects formed with the purpose of giving visibility to their causes and daily struggles, often receiving support from professionals in various areas, enabling the strengthening and unity of collectives,” said Maria da Penha in the Guide’s presentation video.

In the introductory video, Maria da Penha also highlighted the importance and political strength of the Guide’s museums. “Community and social museums make use of their own culture, which is often denied or despised by society. Through the memory of residents, these museums expand their knowledge, transforming it into a tool for change. They generate sustainable practices, which allow the community to remain in its territory, enable the preservation of their customs and habits, and reaffirm the existence of residents as protagonists of their own histories.” She then went a step further saying that, “These [are] spaces of resistance and re-existence, they are the legacy of their creators and have also become a heritage of the neighborhood, the city, and the country, to be respected and preserved by the entire population. Remembering that memory is not to be extinguished, it is not to be removed!”

Touring the Community Museums

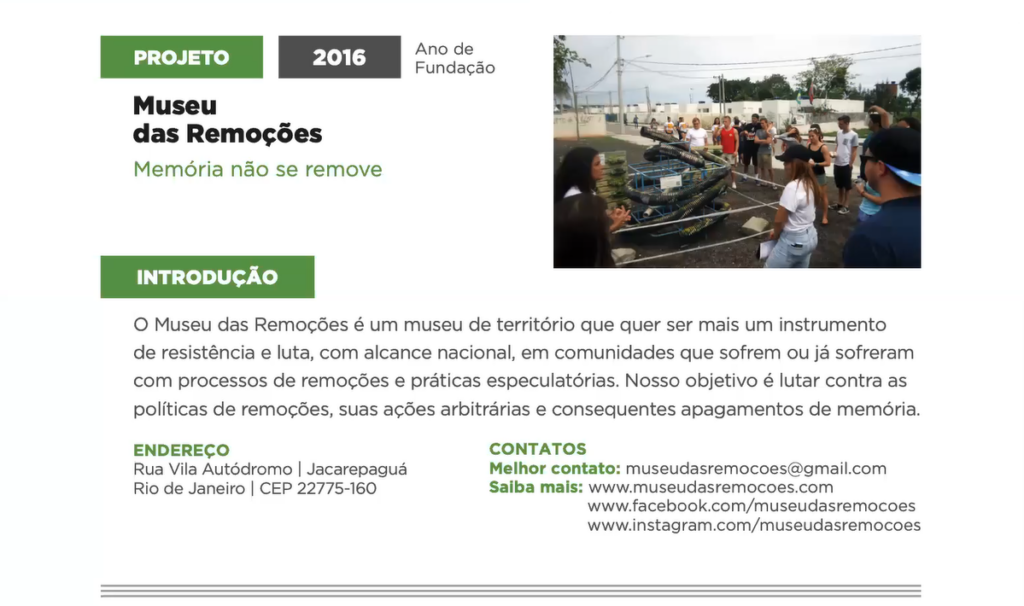

Virtual tours followed, with the viewing of four projects included in the Guide. First to be showcased was the Evictions Museum in Vila Autódromo, West Zone of Rio, represented by Maria da Penha. A video talking about the origins of the Museum was shown, followed by Maria da Penha telling a little of her history with the Museum.

“The Evictions Museum was born amidst demolitions and debris, during a troubled time for us residents who were fighting to remain in our community,” said Maria da Penha in the video. “The Evictions Museum is our legacy, our heritage. We tell our stories. We strive to preserve our memories. We are constantly learning, taking ownership of a city that was once denied to us, but [which] is also ours.”

“The first threat of forced eviction came in 1992 and we’ve been resisting, fighting since, and they haven’t been able to get us out,” said Maria da Penha. “We knew we shouldn’t leave. We also built this city, this country. We work, we pay our taxes. It’s not fair that we have to leave our homes, which we worked hard to build.” She also mentioned that, at the beginning, the residents had no understanding of what the museum would be. “I never imagined that I would be part of a museum because, in my ignorance, I thought that only those who had some legacy in politics or history deserved a museum. Poor people like us had no right to tell our own story. To my astonishment, I found that fighting for my home, I was fighting for my history and my memories.” On May 18, 2021, the Evictions Museum turned five.

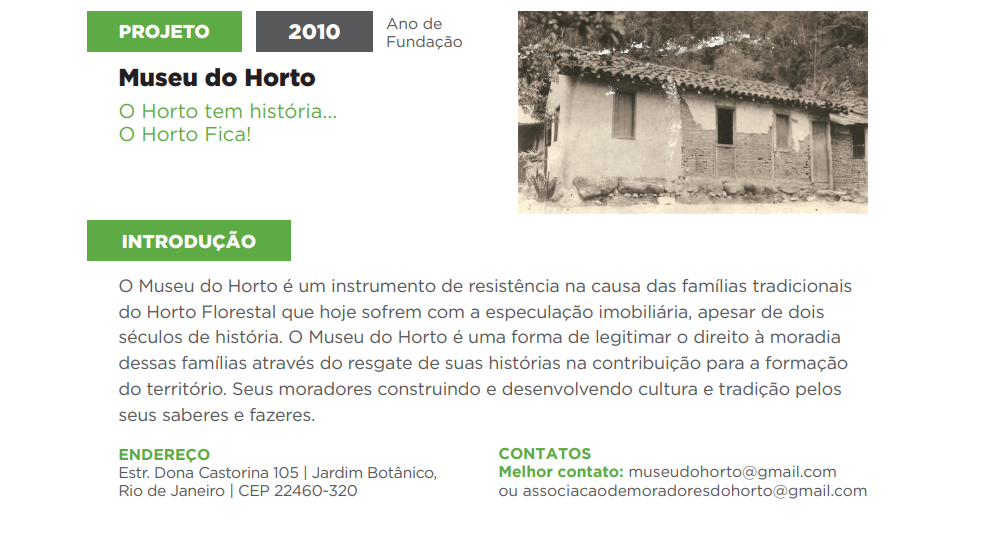

Next came the Horto Museum, from the Horto community in the Botanical Gardens neighborhood, in Rio’s South Zone. Emerson de Souza showed slides and presented the museum, also mentioning the impact of the pandemic on the project. “We made a re-evolution of the museum with the pandemic. There is plenty of love, but unfortunately the [current] situation is not ideal for museums to function,” he said. “Horto has also been experiencing problems with forced evictions promoted by federal agencies, which threaten 621 families.”

Due to the limitations and potentialities of the territory, the Horto Museum declares itself a “museum of paths: there is material and immaterial heritage in these paths. Each one has its particularities and specific dimensions. The Horto community is historical and constitutive of the city of Rio and of Brazil.” Open in 2011, the museum has records from many generations, besides holding mutirões (collective actions) and ecological actions, because, according to de Souza, residents are greatly concerned with caring for nature in the same way their ancestors always did. “Today we see everything that Brazil is going through. We see the world suffering with global warming, deforestation, pollution. Planet Earth is crying out for help. It is important that we pass this on to future generations. In addition, the museum has projects with schools, several architectural heritage sites, and also promotes religious tours, workshops, and events.

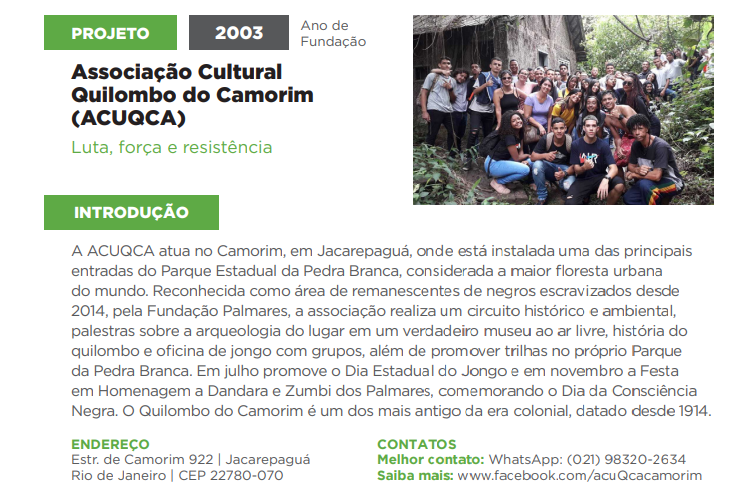

Represented by Adilson Almeida, the Camorim Quilombo Cultural Association was the next to be presented. Almeida said that the Association emerged from the quilombo—as ancestral lands occupied by descendants of enslaved people in Brazil are called—established in 1574 at the site of the old Camorim Mill, in the Pedra Branca Massif, West Zone of Rio. “One of the first runaway slaves from that time is from my family, and I am very proud of that. Their first act of resistance was to arrive at the place, work and flee,” said Almeida. “Besides being an open-air museum, the quilombo is a training school. We have to make this connection between past, present and future. We always talk about the European past, but we have to talk about who made history count, who built this history.”

Almeida says that the Camorim Quilombo is constantly under threat of evictions, but that they still have a lot of fight in them. The quilombo has several vegetable gardens in order to “teach the community to produce its own food.” In 2017, the project came across archaeological finds in the region, finding artifacts from the 16th and 17th centuries, which brought a wealth of material to the local museum. “We also work with schools, so that children can understand their own history and identity. We have to resist to exist every day,” adds Almeida. Not to mention the potential for ecotourism.

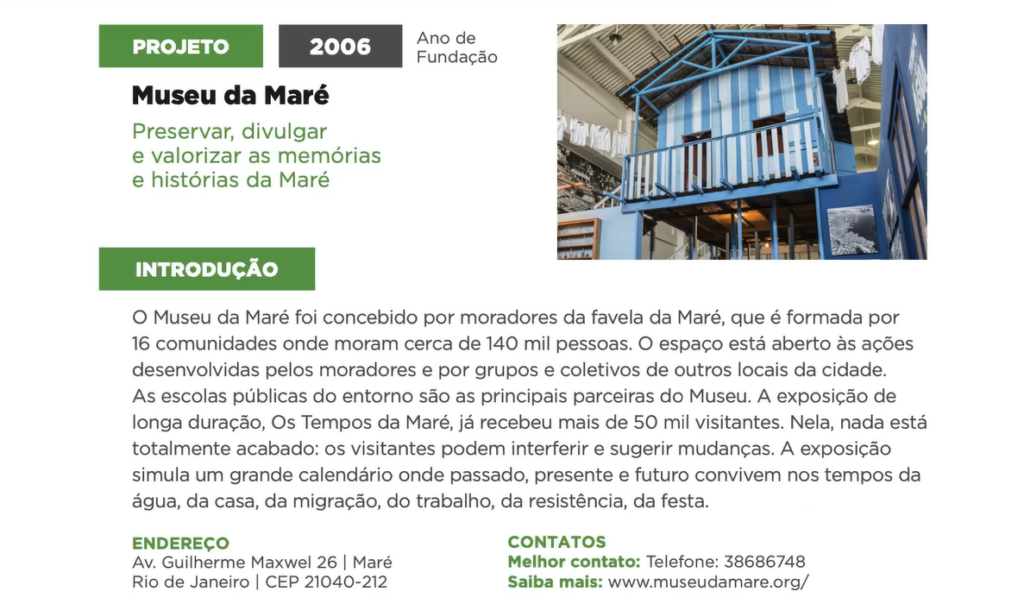

Lastly, the Maré Museum, in Complexo da Maré, North Zone of Rio, brought its presentation with a video and a talk by Lourenço da Silva. The video publicized a campaign in support of the museum. “We believe that memory is a universal right and that the people who live in favelas are not just victims of violence, they are the subjects of their stories and they produce cultural goods of aesthetic, material and immaterial value.”

Da Silva said that the campaign has been a success. “We have raised over R$100,000 (US$19,000). We didn’t expect it, especially during a pandemic. This energized us, because it’s hard enough to keep the museum open with the pandemic,” he said.

“The Maré Museum started out with a group of young people who were tasked by the Catholic Church to film views from the church. This was back in the 1980s. They got excited, turned the camera a bit towards the street, got lost in them with the camera and started to film macumba chants, carnival parades and June festivities. However, the Museum only came into being officially in the 2000s, and since then it has remained solid and represented the community.”

“What we are doing here is a work of resistance, telling the story that has been lost over hundreds of years. There is a feeling of sorrow, because we, as Afro-Brazilians, have lost our memory, our history,” emphasized da Silva. According to him, the mentality of government officials has to change, because the work is necessary: “The government used our cheap labor to build our city and now ignores our memories. We don’t have money, we have our memories, our stories. The Guide is an instrument. We have to value our museums,” he concluded.

The Importance of Preserving Memory During the Pandemic

During the final round of the live event, guests reflected on strategies to preserve memory in favelas and peripheries in times of Covid-19, and how this should be a priority, even in a period of more urgent needs, such as the pandemic of hunger, unemployment, the shortcomings of emergency cash transfer policies and the consequent increase in the number of families living below the poverty line or in extreme poverty. In this very delicate moment of high numbers of cases of coronavirus contamination in the favelas, with high underreporting, problems related to vaccination, a generalized neglect in responding to the disease, and necropolitics as public policy, it is crucial that favela residents mobilize to tell their narratives, preserving the collective memory of favelas amid the humanitarian crisis.

“Regarding the memory of Horto, we have a hard drive to save all the documents. We are trying to use the Internet and social media to preserve our memories in this pandemic,” said de Souza , from the Horto Museum.

Almeida also shared his strategies at the Camorim Quilombo. “We have a lot of material stored: photos, videos, everything’s recorded. We have everything in PDF format. But it’s not just about the museum’s memory. It’s the community’s, as well. We’ve been giving a lot of assistance to the families, to the children. We provide psychological support to children, taking them out of their idleness. We’ve been saving all of this on hard drives.”

Once again, we thank our friends from @comunidadechriste

Baskets of basic foodstuffs are helping our community’s families overcome this difficult moment Photos @_raquelcanellafotografia ⠀

After these statements, questions were asked by the audience. Kelly Tavares, a tour guide, asked about possible partnerships to create a network between tour guides and community museums as a means of strengthening both. De Souza and Almeida argued that this partnership would be beneficial, but that one would always need to rely on local guides. “I advise that whoever works with tourism always meet a local, community-based guide,” said Almeida. Da Silva suggested the idea go further: “I think we could partner up with a university and create a course about our memory spaces. We could have a collective of these guides and devise an itinerary.”

Monica Xavier, activist and facilitator of the SFN’s Income Generation Working Group, asked about the economic difficulties being faced during the pandemic. Almeida and de Souza spoke, in particular, of their problems with the crisis. “The pandemic resulted in a terrible social impact, a lot of people lost their jobs. Mothers lost their jobs, children stayed home because schools were closed. So we did a lot for this fight, helping with food, hand sanitizer, face masks. The impact was enormous, especially with so many lives lost,” said Almeida.

The event ended with much praise and hope regarding the expansion of these projects.

“We have to move ahead and hope for better days,” concluded Maria da Penha.

Watch the Full Event Here:

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are Catalytic Communities initiatives. The SFN is supported by Heinrich Böll Foundation Brasil.