This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

An antiracist world must be fought for on several fronts. Acting in only one isolated area is not enough to heal the abyss left by years of racial inequality in Brazil. It is necessary to act together, with broad participation from civil society, the private sector, and public authorities to deconstruct structural and institutionalized racism. There is no magic bullet. The solution is a path built through hard work and dedication. The steps come from afar and are usually taken by us, black people, but above all by us, black women.

By Us for Us

Cases abound. Redes da Maré, for instance, is a civil society organization which has become a reference for citizen activism in one of the largest favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Founded over two decades ago, the network lives up to its name in the way it is structured. It produces knowledge, develops projects, and promotes comprehensive actions to ensure effective public policies to improve the lives of the 140,000 residents of the 16 favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, in the North Zone.

Working across four axes—Art, Culture, Memories and Identities; Territorial Development; The Right to Public Safety and Justice; and Education—Redes da Maré has managed to ensure significant advances, while promoting important debates about awareness and active citizenship in the community.

Started by current and former residents of the region, Redes da Maré is always attentive to local needs. This focus has contributed to the institution’s broad reach today, and ability to commit thoroughly to important issues—much like other organizations from the Black Movement have fought, and still fight, to guarantee a better life for current and future generations.

Identifying and Ensuring Rights: “Blackology” and Yoruba Philosophical Pathways

“Eshu Throws a Stone Today and Kills a Bird of Yesterday” is a Yoruba saying that became popular after Brazilian rapper Emicida quoted it in the documentary AmarElo—It’s All for Yesterday, which is about the artist’s work and about blackness in Brazil.

Yoruba culture comes from one of the greatest kingdoms in the history of West Africa: the Oyo Empire. In this culture, orality holds a sacred weight. It is the fabric that weaves together peoples’ lives, transmitting their ancestral heritage to the younger generation, and preserving traditional knowledge. Rhetoric and storytelling are historical documents as well as educational practices.

In order to understand oneself as a black person in the diaspora, amid a reality of hierarchies, colorism, and racial inequality, it is necessary to reflect collectively on the topic. It becomes important to honor one’s ancestors, to educate oneself in the collective “doing” of blackology—or black pedagogy—and to strengthen ourselves through our own.

The Maré Census, produced by Redes da Maré, revealed that 62.1% of residents identify themselves as black or brown. From this analysis, several policies were developed to improve race relations in the group of favelas, and thus combat everyday racism. The Black House of Maré was created with this aim, as explained by Pâmela Carvalho, coordinator of Redes da Maré’s Art, Culture, Memories and Identities axis: “We started out with formative roundtables, with the idea of re-educating people on race relations. Having discussions on black masculinities, black grandmothers… On the difference between retail drug sales and drug trafficking; understanding how important it is to racialize the issue of public safety because we, unfortunately, have a very racist public security project in force here in Rio de Janeiro.”

The space aims to promote theoretical, methodological, and political education in order to work through ethno-racial issues, and provide tools to confront structural racism in Brazil. The Black House also runs the Maré School for Racial Literacy, an ongoing training program for black youth that ran from July to December of 2021, with new classes planned for 2022, 2023, and years to follow.

Due to the pandemic, weekly classes were held remotely, with one face-to-face class per month. The training was divided into modules. The first module included theoretical classes to understand racialization in the context of Brazil; the second focused on analyzing audiovisual media from a racialized perspective, including practical knowledge of the topic; and the last focused on the arts in general.

As Carvalho explains, “We’re going to work a lot with rap, graffiti, funk, and the urban arts within these youths’ context, which is something they’ve shown an interest in. The idea is to make this a training course, with about 30 students per class. They will all receive stipends since we’ve realized that many are already in the informal labor market.”

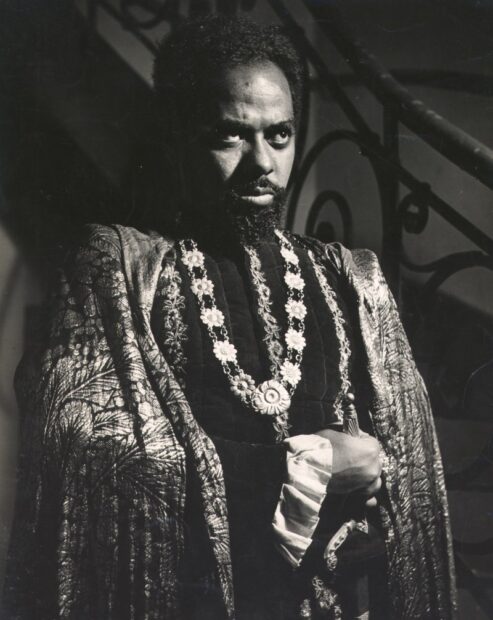

The Black House of Maré also offers shorter-term courses and artistic cultural activities that are open to the general public. These focus on the Afro-Brazilian context, such as a course on the theory of Quilombismo, a concept coined by actor and activist Abdias do Nascimento. Also known today as aquilombamento, both terms originate with the term quilombo—the first territories of freedom from enslavement for Afro-Brazilians in colonial Brazil, having a social and economic model that contrasted with the areas of Portuguese occupation. Quilombos were based on African cultural heritage and values, they could be rural or urban, and were self-sufficient, producing their own food, laws, weapons, etc. although they established commercial relations with surrounding communities under Portuguese rule. Some quilombos had more people than the largest Portuguese-controlled Brazilian cities at the time. Quilombismo proposes this legacy as the foundational reference for the political mobilization of the Afro-descendent population in the Americas, based on their own historical and cultural experiences. It goes even further, in fact, with an Afro-Brazilian proposal for the contemporary national State as a multi-ethnic and pluricultural Brazil.

The Black House of Maré also offers shorter-term courses and artistic cultural activities that are open to the general public. These focus on the Afro-Brazilian context, such as a course on the theory of Quilombismo, a concept coined by actor and activist Abdias do Nascimento. Also known today as aquilombamento, both terms originate with the term quilombo—the first territories of freedom from enslavement for Afro-Brazilians in colonial Brazil, having a social and economic model that contrasted with the areas of Portuguese occupation. Quilombos were based on African cultural heritage and values, they could be rural or urban, and were self-sufficient, producing their own food, laws, weapons, etc. although they established commercial relations with surrounding communities under Portuguese rule. Some quilombos had more people than the largest Portuguese-controlled Brazilian cities at the time. Quilombismo proposes this legacy as the foundational reference for the political mobilization of the Afro-descendent population in the Americas, based on their own historical and cultural experiences. It goes even further, in fact, with an Afro-Brazilian proposal for the contemporary national State as a multi-ethnic and pluricultural Brazil.

“We’re also beginning a research project. The aim is to understand the living conditions of black people in Maré, and we also want to produce material with the Angolan population living in the area of Vila do Pinheiro… We want to dedicate a specific section of the study to this,” explains Pâmela Carvalho.

To help foster these types of initiatives, Casa Fluminense published a guide with local concerns that help residents diagnose their communities’ problems, and create proposals for how to change them. The idea is to encourage them to discuss these proposals with other residents and local politicians, and set up meetings with the vice-mayor or the head of the regional administration.

Like Redes da Maré, Casa Fluminense is also a civil society organization. It acts as a hub for people and partner organizations in specific territories, to build and monitor public policies in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. “Our main strategy is to promote fair, democratic and sustainable development in this region,” says Claudia Cruz, Information Coordinator for Casa Fluminense.

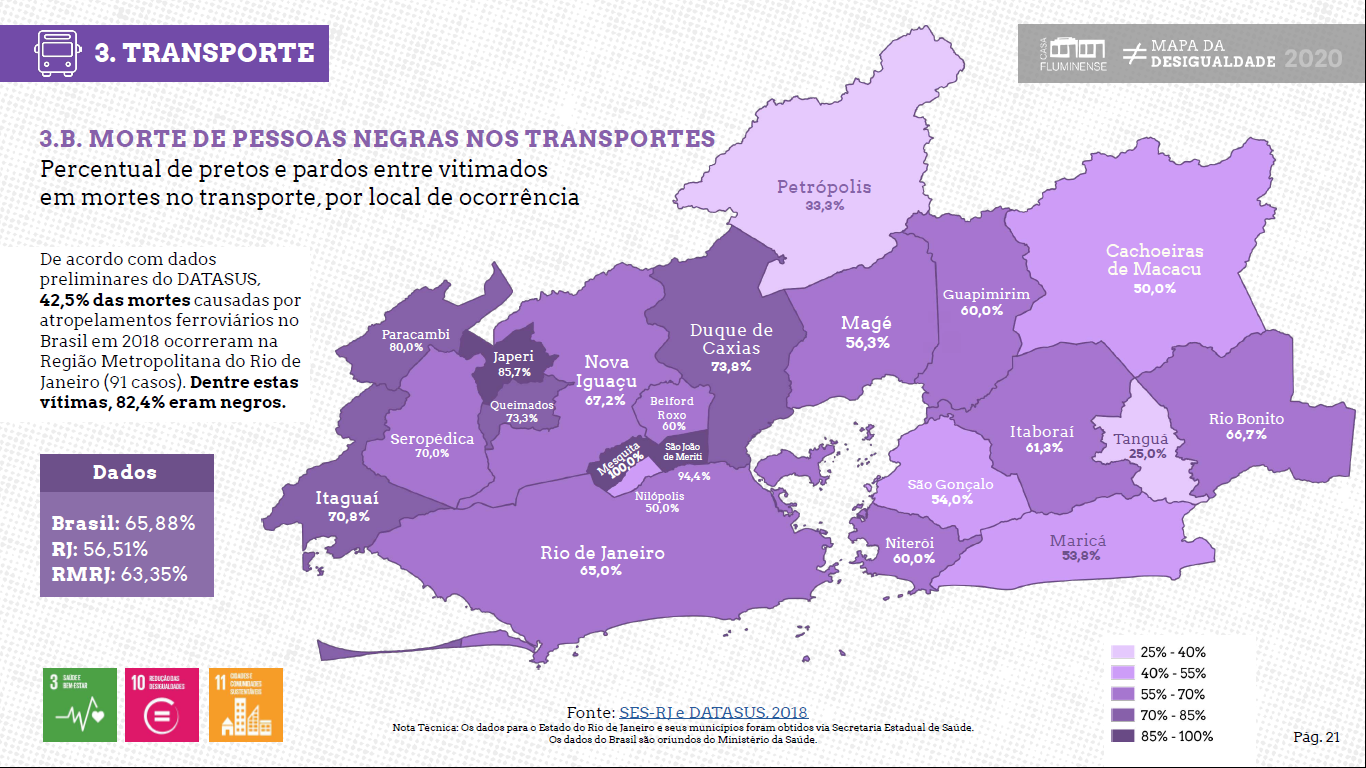

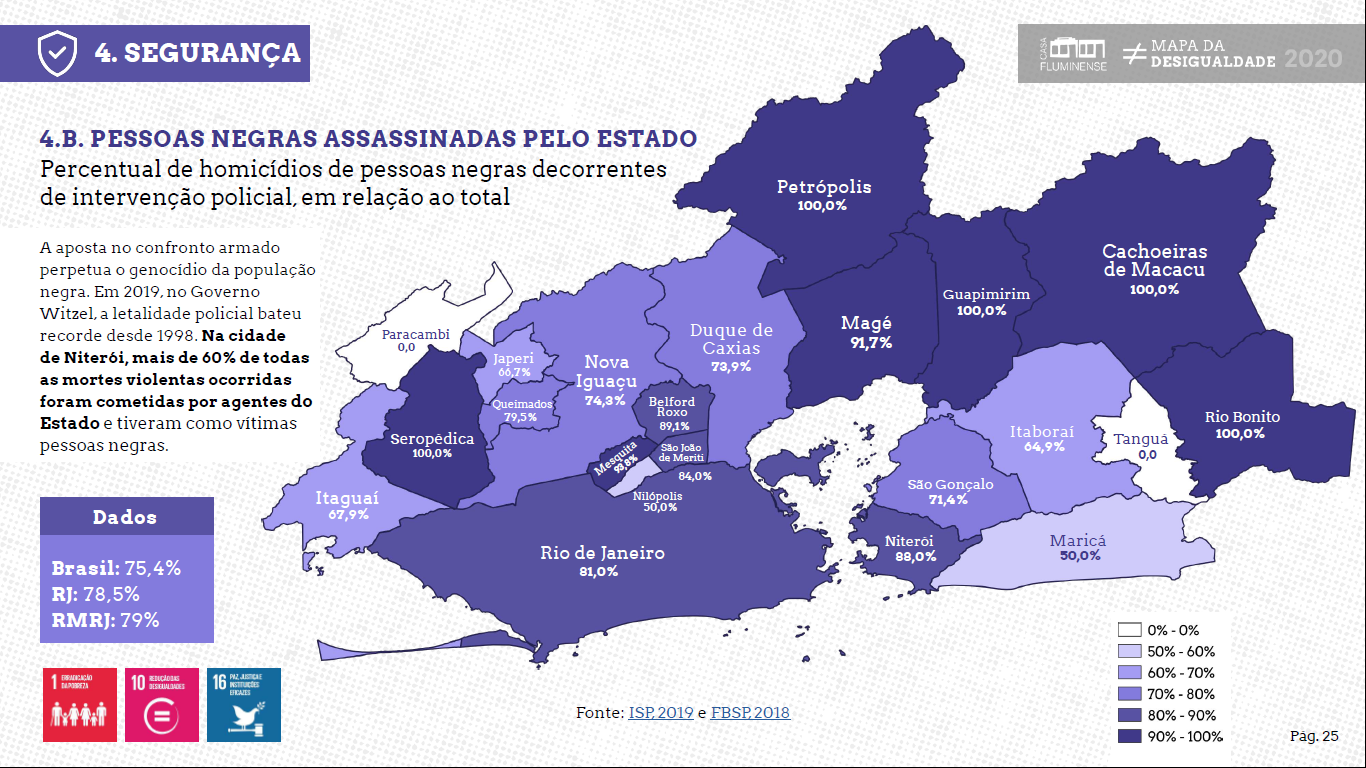

According to Cruz, intersectional racial dynamics are taken into account in everything Casa Fluminense produces. The Inequality Map produced by the organization contains evidence of the social and racial hierarchies that guide its actions. The data speak for themselves and lay bare our racist social constructions.

“In 2018, when we compiled data for the Inequality Map, we saw that 82.4% of railroad accident victims are black, so we released the book ‘It Was Not In Vain’ to talk about this issue. This is notoriously a case of racism because we know that the portion of the population that uses the rail system the most is mainly from [Greater Rio’s] Baixada Fluminense: low-income individuals who are, for the most part, black or brown,” explains Cruz.

Casa Fluminense also analyzes police lethality and violence, which mostly target the black population, besides environmental racism, seeking to identify goals and specific actions to address these problems. In the case of environmental racism, a topic which remains underexplored, the organization’s work seeks to include favelas and peripheries when municipal plans for basic sanitation are updated. “When you can create proposals and analyses and approach your councillors and local politicians showing them how this [neglect with regard to basic sanitation] has been causing illnesses, difficulties, flooding houses, and leading people to lose their homes… you’re doing it to help improve this situation. Dialogue is the best of all worlds,” explains Cruz.

She highlights the Casa’s role as a sort of mediator. Through talks, courses, maps, panels and forums, Casa Fluminense provides information for locals to design their own proposals for improving the city, thus bridging the distance between what is planned by public authorities and what is most urgent for residents.

“We need to build networks that take us from the resident to the mayor, to the governor, or the president, because nobody can do anything alone. That is why Casa Fluminense is so committed to building networks and promoting local actors, so they can work on the inequalities they themselves identify.” — Cláudia Cruz

What Still Needs to Be Done?

Casa Fluminense has approximately 70 partners. These are organizations and collectives committed to social justice, dedicated to ensuring equity, and active in fighting racism. Yet, even with so much work being done, Rio de Janeiro still suffers from deep inequalities aggravated by the pandemic.

These organizations were responsible for promoting basic care, providing coronavirus prevention information, and setting up food drives for those who lost income because of the pandemic, in yet another case of neglect toward the black and poor population.

In July 2020, Rio’s Pontifical Catholic University’s Center for Health Operations and Intelligence released data showing that there were more coronavirus fatalities of black and brown people in Brazil than of whites: “almost 55% of those who died were black and brown, while only 38% of white people died.” Until the period studied, the percentage was higher among black people than white people across all age groups and education levels. In Rio de Janeiro, it became emblematic that the disease’s first fatal victim was a domestic worker.

Cruz emphasizes that Casa Fluminense’s surveys reach the legislative and executive branches. But it’s important to make people more aware of what causes these vulnerabilities. “Casa Fluminense has been trying to encourage local partners to take on advocacy activities, to take an active role in management boards, in health centers, in cultural institutions, and to engage with the city councils and make proposals that have to do with their communities, and that in some way touch upon the racial issue.”

Through Love or Through Pain

Data collection is key to showing evidence of structural racism and it contributes to making the State accountable. It is also important to our understanding of the magnitude of the underrepresentation of black people in different sectors of our society.

In the last general election, in 2018, less than a quarter of the federal deputies identified themselves as black. According to a 2020 survey by the Ethos Institute, only 4.7% of leadership positions in Brazil’s 500 largest companies were held by Afro-Brazilians. According to the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE), about 55% of Brazil is black, and even while they are the majority, Afro-Brazilians are systematically excluded from decision-making positions in the public and private sectors.

In order to promote inclusion in the corporate sector, in large companies, the Identities Institute of Brazil promotes programs for organizations that need to evolve in this respect. With the motto “Yes to Racial Equality,” the non-profit created by entrepreneur, journalist and activist Luana Génot has become a reference.

The group’s administrative and financial director, Tom Mendes, says that many companies have been making a choice for diversity both due to awareness and market pressures. He points out that there is pressure abroad for those who invest in Brazil to look at social, sustainability, and racial questions.

“We create a learning program for these companies, with training, awareness-raising, governance… and through this we build an action plan for the company to take relevant action towards racial equality in Brazil, whether it’s through hiring or raising awareness to have more black and indigenous people in leadership positions.” — Tom Mendes

But there is still a long way to go for this movement to reach the base, favelas and peripheries, and to impact those who need it most. Mendes points out that most entrepreneurs in Brazil are black, but that this is born more out of necessity than desire. It is not the investment of financial resources by individuals who have mastered entrepreneurial processes, nor is it moved by a desire for upward mobility. “Today, companies do have the means to help out locally, but it is quite insignificant. It’s still out of a ‘do-gooder’ attitude. ‘I’m going to help because it warms my heart.’ But we know that if we really want to do something, we need to ensure culture, education in these spaces,” says Mendes.

In the End, Is an Anti-Racist World Possible?

For those who are directly impacted by this system of oppression, there is no alternative but to believe that it is possible. But it takes commitment and participation to demand proportionality and the possibility of social mobilization, otherwise the same cycle of marginalizing black bodies will continue, year after year, in the past, present and future.

“The Ethos Institute released a study showing that we would need 150 years to balance the number of black and white professionals in leadership positions in the job market, but we don’t want to wait that long. We’re in a hurry,” says Tom Mendes.

Cruz defends democratic social control as guaranteed by the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, as the greatest tool in allowing us, as citizens, to exercise our rights and demand change from those responsible for carrying out public policies.

“It’s about occupying these spaces, giving opinions, pointing to data. Any kind of information that can support arguments so that people don’t get run over by the process,” Pâmela Carvalho points out. She highlights the issue of whiteness and the involvement of white people in the anti-racist fight, emphasizing the need to put pressure on public authorities for effective measures in the medium and long term.

“Racism was not invented by black people. We need white people to really engage in the fight against racism because when November [Black Awareness Month] comes around, things get really heavy for black people. It seems that these issues only come up that time of year and that we are the only ones who are responsible for this discussion.” — Pâmela Carvalho

The Eshu oríkì (greeting, praise poetry) quoted in the title of this article reminds us that the struggle for equal rights has been with us for a long time. Black and brown people continue repairing past injustices, while trying to survive with dignity in the present. Anti-racism needs to be a political project, a struggle led by the Black Movement, built through dialogue with allies, and promoting a radical revision of social structures. Anti-racism is urgent so that black lives do actually matter, and so that public policy ceases being about killing us.

Listen to the Accompanying Podcast in Portuguese Here:

About the author: Kelly Ribeiro is a journalist, broadcaster and producer, graduate of Veiga de Almeida University. A resident of Vila Vintém, she is a journalist at Rádio Relógio 580 AM, and a freelance journalist with works published on website Reverb, Revista 451 (Folha de São Paulo), and currently collaborates with the UOL / SPLASH portal.

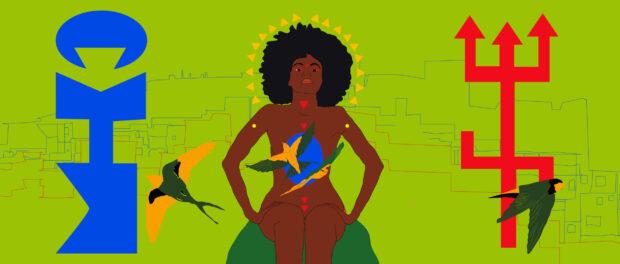

About the artist: Guilhermina Augusti is a visual artist and designer, and a philosophy and audiovisual student. A resident of Fallet–Fogueteiro, her research, artistry, and documentation processes center on issues involving city, body, nature and cosmology, as translated into different types of media.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.