This is our latest article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on climate impacts and affirmative action in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

This is our latest article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on climate impacts and affirmative action in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

The 26th United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP26) was held in Glasgow, Scotland from November 1 to November 12, hosting world leaders and private sector and civil society representatives. COP26 was initially scheduled for 2020, but due to the Covid-19 pandemic was rescheduled for this year.

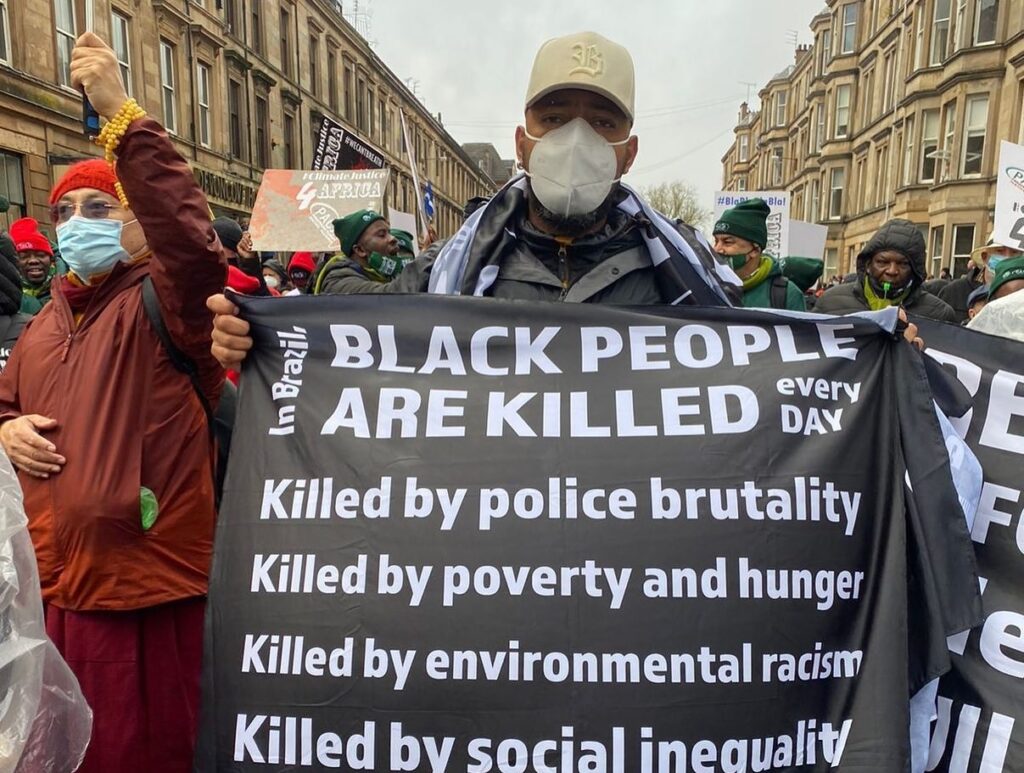

Grassroots leaders from Brazil’s urban peripheries also participated in the conference with the aim of denouncing environmental racism and demanding climate justice. Among those present were members of Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights, PerifaConnection, Favela of Peace Institute, Defenders of the Planet, and EcoCiclo, as well as favela youth who act as ambassadors for the United Nations (UN).

The presence of these figures contrasts with the profile that typically dominates such gatherings. The involvement of peripheral organizations puts those most affected by environmental crises at the center of the debate.

Brazilian Government Vs. Favela Activists

Shortly before COP26, alarming data were released out of Brazil. According to the Estimated Greenhouse Gas Emissions System (SEEG, in Portuguese), the country’s greenhouse gas emissions grew 9.5% in 2020, going in the opposite direction to the rest of the world, which saw an average global reduction of 7% in emissions over this period.

Represented by the Minister of the Environment, Joaquim Leite, the Brazilian delegation in Glasgow attempted to project the image that there is a “mistaken” view of the country’s efforts to fight climate change. With this aim, a luxurious pavilion was built for the event, as reported by activist Kamila Camilo on news site ECOA UOL.

Criticism with the way the Brazilian government has been carrying out environmental policies led President Jair Bolsonaro to opt out of the conference. During the event, Brazil announced an adjustment in its target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from 43% to 50% by 2030. However, the proposal does not represent progress in relation to targets previously established by the country.

By modifying the base year from which the percentage is calculated, the Brazilian government played with numbers to present targets which appeared more ambitious but which, in reality, maintained targets established six years ago. In December of last year, when the Paris Agreement (2015) was revised, the presented proposal—a 43% reduction in emissions by 2030—was worse still, representing a step backwards in relation to the commitments made by the country in 2015.

The targets presented in December were branded “creative climatic accounting.” Because of this, a group of young people filed a civil suit with a federal court in São Paulo against former Minister of the Environment, Ricardo Salles, in April of this year. Marcelo Rocha, Daniel Augusto Holanda, Thalita Silva e Silva, Paloma Costa, Paulo Ricardo Brito Santos and Walelasoetxeige Suruí, who were behind the suit, are environmental activists and members of two organizations which were founded and are led by young people: Engajamundo and Fridays for Future.

The Brazilian government’s participation at COP26 also attracted criticism due to the stance taken by the Minister of the Environment. In his speech at the conference, Joaquim Leite said that “where there is a lot of forest, there is also a lot of poverty.” The Black Coalition for Rights released a statement refuting this comment: “For us, a standing forest means living people. Where there are forests, there is life. Indigenous people, traditional communities and quilombolas [communities descending from enslaved Africans who remain on ancestral lands], among many others, live in the forest. They are the true wealth of Brazil. They are the guardians of the forest.”

In response to the position of the government’s delegation, the parallel pavilion Brazil Climate Action Hub consolidated itself as an important meeting space for those who are fighting for true change in climate policy. In a way, the pavilion gained something of an official status in representing the Brazil delegation, hosting governors, photographer Sebastião Salgado’s Instituto Terra, and promoting concrete proposals for fighting deforestation and in defense of indigenous and quilombola lands.

The conference was also marked by demonstrations organized by favela activists alongside other peripheral actors from around the world. On November 5, there was a protest organized by young people from various parts of the globe. On Saturday (6), the Global Day of Action for Climate Justice march took place.

A resident of Complexo do Alemão in Rio’s North Zone, Raull Santiago was at the conference representing PerifaConnection. He arrived in Glasgow a week before the event started. The idea was to build protests and discussions with other organizations present at the conference. “Activists, groups, social movements, they occupy the COP26 to guarantee the future and discuss an agenda that is so important for the world and also for Brazil, which has the Amazon, the Pantanal, these rich biomes. COP26 is the place to discuss the future starting now. And we are present, Perifa is present, the favela is present,” he said in a video released on Instagram.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Arriving with the gang on the frontline of the fight against the climate and environmental crisis. One more day!

A Carioca View of 10 Years of COP

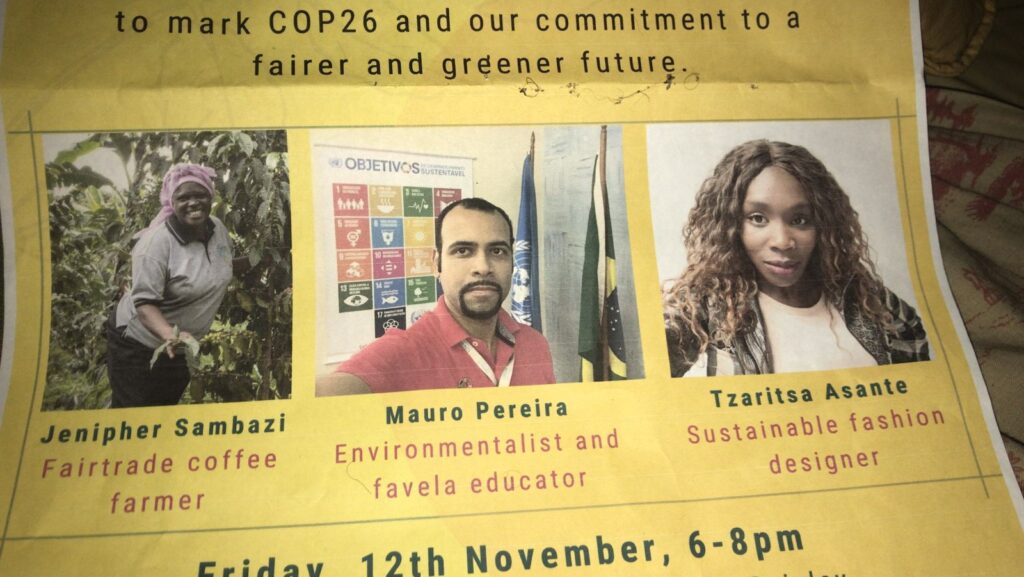

Mauro Pereira, co-founder of Defenders of the Planet, a local Rio de Janeiro NGO which has been fighting for the Serra do Mendanha natural area in the city since 1999 and works with the communities around it in Rio’s West Zone, was also at COP26. Pereira has been attending COP conferences since COP16, in 2010 in Cancún, Mexico, speaking of environmental education in the West Zone favelas and pressuring the conferences’ actors based on the impact of climate change already present in his territory. Pereira was among the movements that lobbied for climate education (Article 12) in the Paris Agreement, in 2015. According to him, the Paris Agreement went beyond governments: it is also a civil society agreement. It was as a result of Paris that Defenders of the Planet brought the climate change debate into their initiatives alongside communities and schools of Rio’s West Zone.

This year, at COP26, Pereira presented the climate change education initiatives their organization carry out in public schools—an example application of Paris’ Article 12—on various panels. He also presented the Rio de Janeiro Sustainable Development and Climate Action Plan, and put pressure on ministers and international representatives, such as the Secretary General of the OECD, “to not give Brazil a seat for as long as [the country] does not respect human rights, the indigenous, and the environment.” He had the opportunity to visit local farmers to learn from their experiences and take them back home. He took part in a panel with community leaders from Uganda and Nigeria, in a vital exchange with leaders across the Global South.

Drawing comparisons with the last conferences, Pereira said: “I could see, at this COP, that a lot of world leaders arrived in their huge airplanes releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, to touch down for a photo and make a nice speech to show that they were there. I was very sad to hear that Australia will not eliminate coal. India, also, asked that the wording ‘phase out’ coal be removed from the final document. For me, this shows that this space has already lost some credibility, it is more prone to words and flowery speeches, than actions. I came out of this COP frustrated with the final agreement. Agreements were reaffirmed, but since COP16 in Mexico, where some progress was made and authorities took a bit more action, I see that today they’re posing for a photo, making a nice speech, thinking more of the economy than of people. I was able to denounce the climatic impacts in my area, which is one of those that will suffer the most from the impacts of climate change. But unfortunately the actions that governments should be taking are moving slowly. I hoped for more. We are living a climate emergency, after all.”

Environmental Racism on the Agenda

The Brazilian Black Movement’s participation in the conference helped strengthen the understanding that it is not possible to speak about the environment without speaking about race. In the words of historian Douglas Belchior, a representative of the Black Coalition for Rights, the movement’s participation is historic. “It is only possible to protect the environment if we protect and guarantee the lives of the people and communities that protect territories and waters through their way of life, as Brazil’s indigenous and quilombolas do.”

Katia Penha, coordinator of the National Coordination for the Articulation of Rural Black Quilombo Communities (CONAQ in Portuguese), was present at COP26. During a speech in the parallel pavilion, she stressed that traditional peoples are not responsible for the climate crisis. “We believe that effective solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions reside in the demarcation of indigenous and quilombola lands; and in the defense of collective land and territorial rights. It is not the population that is black, poor, peripheral, quilombola or indigenous that is responsible for the worsening climate crisis. These are the main populations who are rendered more vulnerable by the irresponsibility of other social and economic groups.”

In Brazil, there are 3,475 quilombola communities spread across the national territory, according to data from the Palmares Foundation. However, less than 7% of these areas have been given land titles.

Environmental racism in an urban context was also an issue discussed during the conference. For Raull Santiago, “climate justice for the favela is the right to live.” In an interview for Ecoa UOL, he explains how the favela population’s rights continue to be neglected. “When we think about climate justice where I come from, we’re talking about a series of factors that aren’t being discussed, and which mean that the reality of life for those who live where I live is one of violence, of inequality, of lack of survival, as a rule,” he says.

For Douglas Belchior, places like COP really need to open up: “The poorest people, the people who suffer most, they have to participate in the spaces of reflection, of discussion, and of decision. We hope that this moves forward, that we don’t take a step backwards, that the next spaces of decision and reflection are no longer occupied by the same actors.”

Building International Support

The actions of peripheral leaders were not restricted to the COP26 agenda. The trip to Europe was also an opportunity to strengthen ties with authorities from other countries, who can lend their support to the struggles taking place on Brazilian soil. After Glasgow, the favela committee went to Paris, Madrid, and Berlin.

This was the case of the group made up of the Black Coalition for Rights, UneAfro, and CONAQ, that traveled on to the French capital and met the city’s Deputy Mayor, Jean-Luc Romero, and councilwoman Geneviève Garrigos. During the meeting, the City of Paris committed to giving political support to the causes of the Black Movement in Brazil, as well as to partnerships for future campaigns in defense of water. It is important to note that Paris is one of the cities in the world that has been a leader in the remunicipalization of water and sanitation services.

In Madrid, the group was received by Maria Dantas, a lawmaker of Brazilian origin. The federal deputy recently managed to get a motion supporting the struggle for human rights in Brazil approved. The meeting, which also involved other lawmakers, discussed the creation of documents which would give support to quilombolas and indigenous peoples.

Meanwhile, another part of the delegation traveled to Germany. The country is strategically important for the defense of the territory of indigenous peoples, as it is responsible for the resources of the Amazon Fund. In Berlin, an agreement was signed for the new German government to intervene directly in the parameters for the allocation of the fund’s resources, so that organizations representing quilombola, fishing, shell fishing, indigenous, and other traditional communities can have direct access to the resources without mediation of the Brazilian government. Another commitment made was to generate international pressure regarding the implementation of decree 4887/03, which regulates the titling of quilombola territories.

To quote Douglas Belchior, if there was anything different at COP26, it was the influence of civil society movements, above all of indigenous peoples and the Black Movement. “In the case of Brazil, we managed to bring this debate to the table and contribute to COP being less exclusive,” he said.

About the author: Euro Mascarenhas Filho is a journalist and contributor to the Piratininga Communication Center (NPC) news service. He is author of the podcast Antena Aberta.