Be it anonymous, from activists, soccer players or artists, the sentiment that echoes in the streets and on digital platforms is a single one: #JusticeForMoïse. The murder of the young Congolese refugee at his workplace, the Tropicália Kiosk, in broad daylight on Barra da Tijuca beach in Rio de Janeiro, caused immense outrage and consternation. The hashtag was one of the most common on social media in Brazil in recent weeks.

On January 24, Moïse Mugenyi Kabagambe, 24, was immobilized and beaten to death at the kiosk where he worked, the Tropicália, at Barra da Tijuca’s beachfront Post 8. The men who murdered Kabagambe are Alesson Cristiano de Oliveira Fonseca, also known as “Dezenove”; Brendon Alexander Luz da Silva, known as “Totta”; and Fábio Pirineus da Silva, known as “Belo.” The three men also worked in the surrounding area: two in Barra beach stands and the other, Totta, a Jiu-jitsu fighter, as a cook at the kiosk next to Tropicália, the Biruta.

As reported by his family, Kabagambe was murdered after having gone to collect late unpaid wages. The total was for two days worked at the Tropicália Kiosk: R$200 (US$38). Kiosk owner Carlos Fábio da Silva testified to the Civil Police on February 1, denying he owed Kabagambe any money but confirming the young man sometimes worked as a day laborer at Tropicália.

This case is yet another that lays bare the violence through which Brazil was built and consolidated: racism, xenophobia, exploitation of workers, and job insecurity. The punches and blows that killed Kabagambe were the intersection of all of this. One anonymous user on Twitter expressed their outrage:

Justiça por Moïse Kabamgabe, mais um jovem preto morto brutalmente em um país que replica os mesmos comportamentos desumanos e escravistas do passado, o país onde o preto vai atrás de seus direitos como trabalhador e não volta para casa. #justicaparaMoise #MoiseKabamgabe pic.twitter.com/z12RQ68Ud7

— kah • 📖: lendários (@kah_gms_) February 1, 2022

Cartoon inscription: “Brazil is a mother that embraces everyone” | Tweet: Justice for Moïse Kabamgabe, yet another black youth brutally murdered in a country that replicates the same inhumane and enslaving behaviors of the past, a country where a black person goes out to demand their rights as a worker and doesn’t come home.

Journalist Jairo Gonçalves questioned the role of race in the assassination of Moïse. Would the same happen to a white man? \

Alguém imagina isso acontecendo com uma pessoa branca? Teve as pernas e mãos amarradas e foi espancado até a morte. Racismo nunca deve ser relativizado. NUNCA! #JusticaparaMoise https://t.co/Fxrjgmqs0A

— Jairo Gonçalves 🌟 (@jairoo) January 30, 2022

Can anyone imagine this happening to a white person? He had his legs and hands tied up and was beaten to death. Racism should never de relativized. NEVER!

Moïse Kabagambe, a Refugee

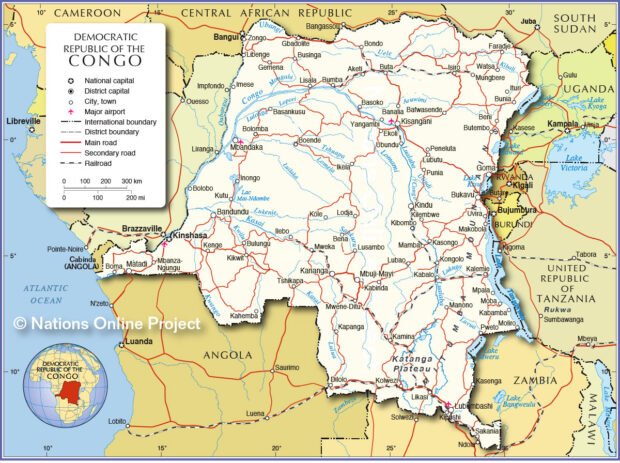

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC, is the fourth largest African country in terms of population, and possesses countless natural riches, with minerals being the best known. Since colonization by Belgium (1885-1960), the diversity of metals such as gold, iron, uranium, and cobalt have attracted the interest of global powers. Over the course of the country’s history, these interests have generated a series of armed conflicts that marked the world.

The country was the scene of the continent’s largest conflicts, the First Congo War (1996-1997) and the Second Congo War (1998-2003). The latter killed approximately 3.8 million people and was the largest war in the modern history of Africa, the armed conflict with the highest death toll since World War II. For this reason, it is also called the African World War. Although it officially ended in 2003, the Democratic Republic of the Congo continues to have armed conflicts in certain provinces to the east. In 2020, according to the UN, over 600 human rights violations occurred per month, with at least 200 executions. This forced millions of families to seek refuge in other nations as a way to escape the horrors of war.

According to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are over 918,000 refugees and asylum seekers from the DRC in other African countries. Together, the UNHCR, the International Organization for Migrations (IOM) and Pares Cáritas-RJ (a Rio-based refugee assistance organization) released a statement of regret over Kabagambe’s murder. In the statement, the organizations state that they “received, with great dismay, the news of the death of Congolese refugee Moïse Kabagambe, 24, brutally beaten in Barra da Tijuca, West Zone of Rio de Janeiro.” In another section of the text, the organizations declared that the Congolese “was loved by the whole Pares Cáritas RJ team, who watched him grow up and integrate.”

As equipes do ACNUR, @parescaritasrj e da @OIMBrasil receberam, com consternação, a notícia da morte do refugiado congolês Moïse Kabagambe, de 24 anos, brutalmente espancado na Barra da Tijuca, zona oeste do Rio de Janeiro.

Mais informações: 👉 https://t.co/WAyWd4Fsqy pic.twitter.com/i2NXT8ca7I

— ACNUR, Agência da ONU para Refugiados (@ACNURBrasil) January 31, 2022

Moïse Kabagambe, a Congolese citizen, tried to escape the hard reality of his country by taking refuge in Brazil. What he and his family did not expect was that reality would also be very difficult for them here. They did not imagine that he could become a victim of racist colonial violence on Brazilian soil.

Você vem para um país em busca de refúgio da guerra, mas acaba encontrando mais violência. Quatrocentos anos após a escravização e as narrativas se repetem. A pergunta é: até quando? #justicaparaMoise pic.twitter.com/Ai8vWxn8F4

— Quilombo Geek (@QuilomboGeek) February 2, 2022

You come to a country seeking refuge from war but you end up finding more violence. Four hundred years after enslavement and narratives keep repeating themselves. The question is: for how much longer?

Humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has been operating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo since 1981. The day on which Kabagambe’s case came to light, the entity made a series of posts on Instagram about the reality of the country and of Congolese refugees, with the objective of raising awareness about the conditions that resulted in the refuge of Kabagambe and of millions of Congolese around the world.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Racked by armed conflict, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has sustained decades of successive multiple crises. This vicious cycle of violence leads to an increasing number of dead and wounded and people forced to flee in search of survival.

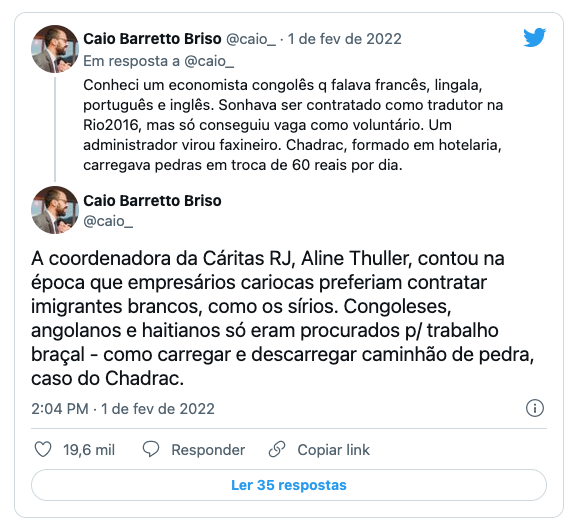

In the context of Moïse Kabagambe’s murder, a report by journalist Caio Barretto went viral, in which he shared that he met Kabagambe when he did a story about the lives of the Congolese in Rio. On this occasion, he became close to one of Kabagambe’s friends, Chadrac, and subsequently to others who were part of this group of friends. Barretto revealed that, despite having excellent training, they were consistently subemployed.

First tweet: I met a Congolese economist who spoke French, Lingala, Portuguese and English. He dreamed of being hired as a translator during the Rio2016 Games but all he got was a spot as a volunteer. A manager became a janitor. Chadrac, who has a degree in hotel management, carried rocks in exchange for R$60 a day.

Second tweet: Cáritas RJ coordinator, Aline Thuller, told me at the time that Rio businessmen would rather hire white immigrants, like Syrians. The Congolese, Angolans and Haitians were only sought for physical work—like carrying rocks and unloading trucks filled with boulders, like in Chadrac’s case.

In another tweet from this thread, Barretto points out the failures of the recent center-left and far-right governments in creating public policy that help these black and non-white immigrants and refugees. He points to structural racism as responsible for this situation.

A situação dos congoleses, angolanos e haitianos no Brasil é terrível e atravessa governos de centro-esquerda e extrema-direita de forma surpreendentemente parecida. O racismo estrutural bloqueia avanços profundos. Eles têm as nossas lágrimas, mas só podem contar com eles mesmos.

— Caio Barretto Briso (@caio_) February 1, 2022

First tweet: Luta fled to Brazil with his pregnant wife. He dreamed of being a soccer player in the country, but ended up in subemployment. One time, I called him up to find out how they were doing: Vencedor had died. According to the dad, from malnutrition, since all the family had to eat was “fufu” (cornmeal in Lingala).

Second tweet: The situation of the Congolese, Angolans and Haitians in Brazil is terrible and sails through center-left and extreme-right governments in a surprisingly similar way. Structural racism prevents real progress. They have our tears, but all they can really count on is one another.

Mourning the murder of Kabagambe, historian Luiz Antônio Simas noted the significant historical relationship that Rio de Janeiro and Congo share. He pointed out that one Rio’s and Brazil’s greatest cultural heritages is a legacy from Congo: samba.

O Congo civilizou o Rio de Janeiro. O melhor que existe nessa cidade terrível e bela, filha da morte e da chibata, veio do Congo: samba. Caguem no mito de merda do carioquismo. A chance do Rio é se reconhecer como monumento do horror. E aí, quem sabe, o Congo nos redima.

— LUIZ ANTONIO SIMAS (@simas_luiz) February 1, 2022

Congo civilized Rio de Janeiro. The best thing about this terrible and beautiful city, daughter of death and of the whip, came from Congo: samba. This screws with the myth of all being native carioca. Rio’s chance is being recognized as the capital of horror. And then, who knows, the Congo might redeem us.

Activists and Artists Speak Up

The response of activists and anti-racist movements also echoed on social media. On his platforms, Raull Santiago, media organizer for Perifa Connection, asked the Congolese people for forgiveness.

Eu peço perdão e desejo os meus mais sinceros sentimentos ao povo da República Dominicana do Congo, que teve um de seus filhos assassinados de forma covarde em meu país, onde veio em busca de dias melhores diante da guerra e da fome no Congo! 😣#JusticaPorMoiseMugenyi (+)

— #JustiçaParaMoise | Santiago, Raull. (@raullsantiago) February 1, 2022

I ask forgiveness and offer my deepest condolences to the people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, that had one of its children so cowardly murdered in my country, where he came in search of better days in the face of war and famine in Congo!

On February 2, the Black Coalition for Rights filed a complaint on the crime against Moïse Kabagambe with the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD). The document indicated the crimes of racism and xenophobia against Kabagambe.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Original post: “Either the UN takes a stand or it will be complicit. The world needs to know that Brazil is a racist country where, in 2022, it is still possible to tie a black person by the hands and feet, beat them and club them to death,” says Belchior to the column.

There is evidence that members of the militia were responsible for Moïse’s brutal murder. The same militia that murdered Marielle Franco. The same militia that occupies the country’s central power and runs the policy of genocide of the black Brazilian people.”

Second post: Outrage, indignation, sadness and hatred. How can we not feel them? How long will we have to live with the smell of death and with the bloodstains of our brothers and sisters, of our friends, of our children.

Yesterday, civil society organizations, organizations of family members of the incarcerated, and the black movement took reports on the absurd violations of rights of imprisoned people to the UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture. In a country where we allow torture and brutal murders to happen in our streets in broad daylight, just imagine what happens inside prisons!

We’ll fight to the end.

Artists also reacted to the crime on social media. Singers, writers, athletes, and celebrities were dismayed by what happened. Singer Ludmilla spoke up quoting Elza Soares‘ famous song in her tweet about Kabagambe.

Moïse Kabamgabe, um imigrante congolês que veio ao Brasil buscando refúgio e para tentar uma vida digna, foi amarrado, espancado e morto em seu local de trabalho apenas por cobrar seu salário atrasado. Mais uma vez a carne mais barata do mercado é a carne negra.#justicaparaMoise pic.twitter.com/YXE99pO2S1

— LUDMILLA 🤙🏾 (@Ludmilla) February 1, 2022

Moïse Kabagambe, a Congolese immigrant that came to Brazil seeking refuge and a dignified life was tied up, beaten and killed at his workplace simply for asking to be paid his late wages. Once again, the cheapest meat on the market is black meat.

Samba singer and composer Teresa Cristina questioned the authorities about what is being done to solve the case and asked “Who killed Moïse Kabagambe?”

QUEM MATOU MOISE KABAGAMBE? QUAL O NOME DESSE ASSASSINO? O QUE OS GOVERNOS(MUNICIPAL, ESTADUAL E FEDERAL) ESTÃO FAZENDO PARA SOLUCIONAR ESSE CRIME E AMPARAR A ESSA FAMÍLIA?#justicaparaMoise pic.twitter.com/M0H0CzSY3m

— Teresa Cristina (@TeresaCristina) February 1, 2022

Who killed Moïse Kabagambe? What is the name of this murderer? What is the government (city, state and federal) doing to solve this crime and support this family?

Caetano Veloso, one of the icons of the Tropicália musical movement of the 1960s, used his social media to grieve the murder. The singer said he cried thinking about the violence done to the young refugee and the fact that the kiosk where the crime occurred bears the names of his historic movement.

Chorei hoje lendo sobre o assassinato de Moïse Mujenyi Kabagambe num quiosque na Barra da Tijuca. Que o nome do Quiosque seja Tropicália aprofunda, para mim, a dor de constatar que um refugiado da violência encontra violência no Brasil. pic.twitter.com/eKIHmYM0xj

— Caetano Veloso (@caetanoveloso) February 1, 2022

Text on photo: Racism and xenophobia. Rio de Janeiro City Government suspends license of kiosk where Congolese Moïse Kabagambe was murdered. | Tweet: Today, I cried reading about the murder of Moïse Mujenyi Kabagambe at a Barra da Tijuca kiosk. The fact that the kiosk’s name is Tropicália deepens, in me, the pain of realizing that a refugee from violence may find violence in Brazil.

Moïse Kabagambe loved soccer and was known for being a Flamengo fan. Through social media, the sports club showed solidarity with the family and expressed sympathy.

O Clube de Regatas do Flamengo lamenta imensamente a morte de Moïse Kabagambe e presta sua solidariedade à família do jovem congolês neste momento de total consternação. #CRF

🖤🙏🏿✊🏿— Flamengo (@Flamengo) February 1, 2022

Clube de Regatas do Flamengo deeply regrets the death of Moïse Kabagambe and would like to offer our solidarity to the young Congolese’s family in this moment of great distress.

One of Flamengo’s main players, athlete Gabigol, stated that Brazil cannot deem facts such as this one normal, and demanded justice.

Esse não é o Rio que aprendi a amar e que me recebeu de braços abertos!!! Queremos justiça, não podemos normalizar crimes como esse!! Que seja feita justiça a Moïse Mugenyi e toda sua família!! Estamos juntos de vocês!!! ✊🏾✊🏿 #JusticaPorMoiseMugenyi pic.twitter.com/nAiVTwepaE

— Gabi (@gabigol) February 1, 2022

This is not the Rio I learned to love and that welcomed me with open arms!!! We want justice, we cannot normalize crimes like this one!! May justice be realized for Moïse Mugenyi and his entire family!! We are with you!!

The commotion felt by players crossed national borders and Brazilian striker Antony, who plays for Ajax, a Dutch club, and for the Brazilian national team, also spoke up on social media in memory of Kabagambe. After the February 1 game between Brazil and Paraguay for the World Cup qualifiers, the soccer player posted his tribute to the Congolese man.

Pra você, Moïse!! Nossos pensamentos com vc e sua família!! ✊🏿✊🏾 #JusticaPorMoiseMugenyi pic.twitter.com/LHtEsI5Bb6

— Antony Santos (@antony00) February 2, 2022

For you, Moïse!! Our thoughts are with you and your family!!

Latest Developments

In response to the case that happened at the Tropicália Kiosk, city councillors Tarcísio Motta and Tainá de Paula announced measures on their social media. Motta sent a letter to the City and to concessionaire Orla Rio, responsible for managing beachfront kiosks in the region, beginning proceedings to revoke Tropicália’s license.

Quiosque é concessão pública! Enviamos ofícios à Prefeitura e Orla Rio demandando processo administrativo p/ cassação do funcionamento do Quiosque Tropicália. São graves os relatos de q a gerência estaria envolvida no assassinato de Moise Kabagambe. Isso demanda apuração urgente! pic.twitter.com/Np12Zjy6GC

— Tarcísio Motta (@MottaTarcisio) January 31, 2022

Kiosks are public concessions! We have sent notifications to the City and to Orla Rio demanding that proceedings be started to suspend the activities of the Tropicália Kiosk. Reports that management was involved in the murder of Moïse Kabagambe are serious. This demands urgent verification!

Councilwoman de Paula also sent a letter to city government, asking that the City request the police to breach the secrecy of the investigation and guarantee assistance to the family.

A Constituição Federal e o Código de Processo Penal apresentam a possibilidade de sigilo em determinadas investigações, mas a repercussão desse caso pede a apuração pública: é recorrente que casos de racismo, mesmo os que têm como resultado a morte, não tenham solução.

— Tainá de Paula (@tainadepaularj) February 1, 2022

First tweet: Still on the murder of Moïse: today we sent notification to the City requesting that the police be asked to breach the secrecy of this investigation and that the family be given the necessary assistance. Fighting racism also means making those who committed such a brutal crime accountable.

Second tweet: The Federal Constitution and the Code of Criminal Procedure provide for the possibility of confidentiality in certain investigations. However, the repercussions of this case demand public verification of facts: it is recurrent that cases of racism, even those resulting in death, are left unsolved.

All over the country, social media mobilizations demanding justice for Moïse Kabagambe have mostly revolved around in-person demonstrations that have already been held or that will still take place. Kabagambe’s murder was so brutal that, outside Rio, numerous cities realized acts in solidarity.

In São Paulo, the protest was held on Saturday, February 5, at 10am at the free-standing space under the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP), as well as in cities in the state’s interior such as Araraquara, São José do Rio Preto and Pindamonhangaba, where demonstrations were held on the same day and time. In Rio Grande do Sul, a rally is taking place today, February 12, in the city of Santa Maria. In Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, the February 5 meeting point was Praça Sete, a traditional stomping ground for protests in the capital of Minas Gerais.

In Rio de Janeiro, the city where Moïse Mugenyi Kabagambe was murdered, the Justice for Moïse Protest was held on Saturday, February 5, at 10am, in front of the Tropicália Kiosk at Barra da Tijuca beach’s Post 8, where the young man lost his life. The march was called for by Kabagambe’s family and by organizations from the Black Movement.

About the author: Euro Mascarenhas Filho is a journalist and contributor to the Piratininga Communication Center (NPC) news service. He is author of the podcast Antena Aberta.