On October 7, a portion of the wall that surrounds the Camorim Quilombo archeological site, in the West Zone of Rio, was torn down. The structure was not a target of vandalism, nor did it suffer the effects of weathering. The wall was damaged by machines operated by Rio de Janeiro’s waste management utility, Comlurb, in order to clean a neighboring waste site. The incident, which took place more than two months ago, caused a major headache for those living in the quilombo—as ancestral lands occupied by descendants of enslaved people in Brazil are called. With no response from the accountable public agencies, the residents themselves have been taking turns watching over the space, in addition to insistently seeking support from the authorities.

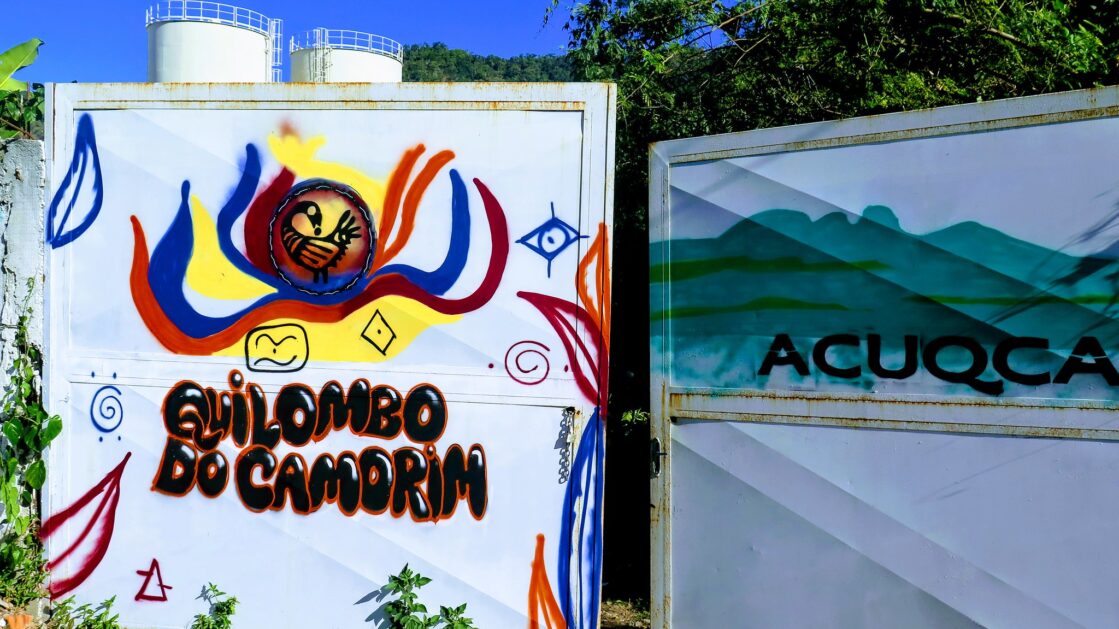

The incident that occurred on October 7 was the second in less than a year. In December 2020, employees of the utility removed debris and garbage from the area using a tractor. During a maneuver, the machine hit the wall and knocked part of it down. Adilson Almeida, president of the Camorim Quilombo Cultural Association (ACUQCA), recalls he was at home when the call came through on December 5 of last year. “They broke a part of the wall and threw the rubble into the lot. I immediately got in touch with the area inspectors [Jacarepaguá administrative region]. They showed up the next day, looked at it and said they’d fix it, and nothing happened. Time went by and now we have this new episode.”

According to Almeida, once again those responsible for the Jacarepaguá region went to the site and committed to the repair, which has not happened to date. A small part of the building materials was indeed delivered, but the labor for the actual repair was never sent. The material sent is being kept secure by residents.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

CITY TEARS DOWN PART OF QUILOMBO WALL

This is just too much indifference—it’s tiring, it’s discouraging but we’re not giving up. We will continue to demand compensation for the damages caused, for the second time, to our property.

We have sent yet another request to the City of Rio de Janeiro and await a solution.

Follow our previous posts to better understand the case.Rio de Janeiro, December 15, 2021

To the City of Rio de JaneiroDear Sirs,

With this letter, we would once again like to request that emergency measures be taken regarding the wall surrounding the Camorim Archaeological Site/Quilombo.

On October 7, 2021, we had a second episode caused by a disastrous maneuver made by COMLURB while collecting garbage and rubble which destroyed part of the wall surrounding the Camorim Quilombo, an important archaeological site protected by the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN), which is furthermore an area of historical, cultural and environmental preservation that holds cultural and educational activities.

On this occasion, the quilombo‘s directors were forced to sleep in the street, in front of the hole, in order to prevent invasions.

After notifying the City verbally and following the visit of IPHAN technicians to the site, we received some of the materials destined to repair the wall, although they were insufficient and, left out in the open, have started to decay.

We are currently, once again, left to our own devices with the entire area made vulnerable to invasions and vandalism since no one has returned to continue the work or to give us an update on the repair schedule.

It is worth mentioning that the first episode happened exactly one year ago when COMLURB made a hole in the wall which, in spite of management’s efforts, was never repaired.

We find this complete disdain for our cultural and environmental heritage, as well as with the quilombola people, regrettable and await immediate measures, always placing ourselves at your complete disposal for all necessary clarifications.

Looking forward to your response,

Adilson Almeida

President of Quilombo do Camorim

An Archaeological Site Under Threat

The wall that was torn down protects an important area of historical and environmental preservation for the state of Rio. The Engenho do Camorim Archaeological Site was recognized in 2017 by the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). This should guarantee the area’s preservation as an official archaeological and heritage site; an archaeological site is an area where traces of human occupation that have scientific relevance to the historical understanding of humanity are found.

Research is often carried out in the area of the archaeological site. Since 2016, archaeologist Sílvia Peixoto has been conducting research and excavations at the site. As a result of her work, thousands of pieces and fragments have already been recovered. These are materials dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries, which tell the story of the early stages of sugar mills. Part of this material is in the National Museum, but there is still a lot left to study on site.

“We have an open-air museum, which is the excavation area of Silvia Peixoto’s doctoral research. At the site of this open-air museum, on the wall and on the ground, there’s still a lot of material. Not knowing what it is, people can destroy it,” explained Almeida. IPHAN has been briefed on the vulnerability of the preservation area. The agency forwarded a request for repair to the City, and scheduled a technical visit to the site on January 18, when it will have been four months from the second incident with the wall that protects the archaeological site.

“This really is an area that needs care and attention from public agencies, for it contains historical and environmental heritage,” said Almeida. In addition to the archaeological site, the wall protects a large area of vegetation, which extends to the Pedra Branca State Park. In this area, events and outreach projects are held with the Camorim community, besides there being guided visits to a historical site. “We’ve been doing continuous work with public schools, talking about the history of the quilombo, explaining what a quilombo is, how it came about,” he adds.

A Quilombo Fighting for its History

The archaeological site is part of the Camorim Quilombo area, officially recognized as a quilombo by the Palmares Cultural Foundation in 2014. The recognition of the territory as a quilombo and the registration of the archaeological site by IPHAN has guaranteed protection to an area that holds great historical and environmental value, although this measure arrived late. The region where the quilombo is located suffered real estate pressure on the eve of the Olympic Games in 2016. Part of its territory was acquired by a construction company, which erected a group of buildings on top of the history of slavery in the region.

In early 2013, construction company Living, which is part of the Cyrela group, acquired the land claimed by the quilombo, removed the community’s soccer fields, tore down native Atlantic Forest and built the Olympic Media Village, which hosted journalists during the games, and was later made available on the real estate market as private apartments. Thus, within a few years, one of the oldest quilombos in the state of Rio became next-door neighbors to a group of condos.

According to Almeida, in recent months, Camorim residents have been replanting trees in an attempt to reconstitute the degraded green space. He, like other quilombo residents, descends from the history buried underneath the residential complex. They are among the generations descended from enslaved Afro-Brazilians who worked in the old Camorim Mill, built in the 17th century. All that is left from this era is a small chapel, located in a central area of the quilombo and close to the wall that has been torn down.

For those who recognize themselves as quilombolas in Camorim, knowing and preserving their history is a constant struggle. Created almost 20 years ago, ACUQCA emerged with the mission of representing this struggle—which acquires new chapters, but continues to be contested and disputed. However, the leaders of Camorim, who protect and care for the archaeological site, will continue to persist and mobilize towards the preservation of their territory.