This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, favela organizations have been the primary leaders in fighting Covid-19 in their territories. Now, with the new rise in cases, it has been no different.

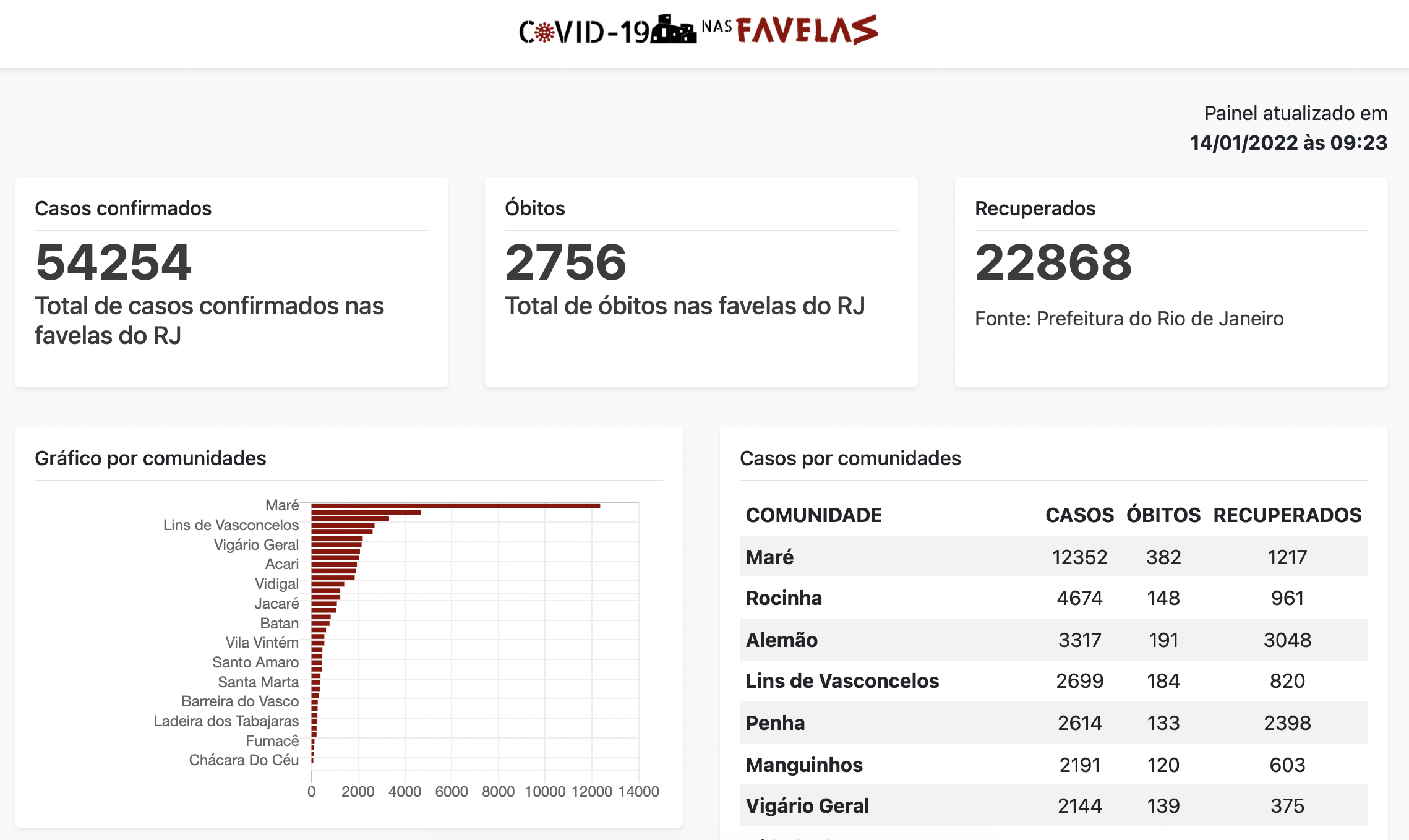

The number of Covid-19 cases has once again risen in Brazil. Most infections are being caused by Omicron, a more transmissible, but less severe, variant. This is one reason why the death rate has been lower in relation to the increase in cases. The other key factor is the progress of vaccination in the country, where 76% of the population is immunized. According to data from the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard*, mortality in Rio’s favelas has decreased from 6.97% before November to 1.01% since then, thanks to these advances.

Still, the latest news shows crowded health facilities with people reporting symptoms such as body ache and fever. Earlier this month, the testing center at Vila Olímpica, in the favelas of Complexo do Alemão, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, for instance, carried out 461 consultations in a single day. Nearly half—203—tested positive, according to information from the Voz das Comunidades newspaper. Rio’s favelas have accounted for over 125,000 cases and 7,400 deaths since July 2020, as shown by the most recent update from the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard, in partnership with Brazil’s national health foundation, Fiocruz and 23 other community organizations.

The country’s new wave of contagion became even more worrisome after the December 10 data blackout, which affected the Brazilian Ministry of Health’s public information databases. Following a hacker attack, platforms such as Open Data SUS, Painel Coronavirus, and Localiza SUS were unstable making it difficult to notify new cases and deaths. Renata Gracie, a Fiocruz researcher and participant in the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard, says that the information disclosed in the Ministry of Health’s Epidemiological Bulletin may still contain inconsistencies. “Analyses are being carried out, but there may be [an inaccuracy] in the information, especially with regard to vaccination.” Data entry into the public systems has already been re-established, but there is some instability and delay in updating the information.

Gracie also explains that, even before the blackout, some systems already showed incomplete information. This is the case of SIVEP-Gripe [the Ministry’s respiratory infection surveillance registry]. In September of last year, Fiocruz published a statement exposing the situation: “The Covid-19 vaccination data for each of Brazil’s states made available by the SIVEP-Gripe database, present a substantial amount of incomplete information, which seriously compromises any analysis of the effectiveness of vaccines,” states an excerpt from the document. The information requested by the institution concerns the vaccination data on people hospitalized with Covid-19: if the patient was vaccinated, date of immunization and the batch of the doses.

As for the actual situation of the pandemic in favelas, the scenario is even worse. The data regarding these territories are not properly accounted for by public authorities. It was trying to change this scenario that several initiatives emerged. One of these is LabJaca, a research, training and data production and narratives laboratory on favelas and the periphery, located in the favela Jacarezinho, in Rio’s North Zone. The group is formed exclusively by black youth. The goal is to facilitate access to research using audiovisual media as the primary means. Co-founder Mariana Galdino talked about the origins of the collective: “We emerged to bring about citizen-generated data. This way, we become the subjects of our plans, our life experiences, and our social and political demands. I believe that our work contributes, first and foremost, to the veracity of the facts. What could be more important in a pandemic than information?” she asks.

A lot of data are collected by LabJaca from everyday situations. At the start of the pandemic, the group observed that the main beneficiaries of the campaign “Jaca Against Corona”—that distributed baskets of basic foodstuffs in the community—were black, female homemakers who were suffering from unemployment and domestic violence. This finding motivated the next survey to be launched, to map the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic on the lives of Jacarezinho residents. “These are situations that we perceive from our practical reality,” says Galdino. To carry out the study, LabJaca launched a crowdfunding campaign, open to donations until January 31. “People should donate to our cause for the defense of evidence, of science,” argues co-founder Galdino.

Another example of an organization that continues to fight Covid-19 is the Association of Women of Itaguaí—Warriors and Social Articulators (A.M.I.G.A.S.), located in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense, that has been notifying cases of the disease through the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard. That was not the case at the beginning of the pandemic. At the time, data obtained by the women was written in a notebook. But with the launch of the online platform in July 2020, the accounting became easier. Anna Paula Salles, president of the Association, talked about the change. “The Unified Dashboard is a technological tool. It works like an instrument that voices the problems that people detect within their community. We take the information from our notebook and transfer it to the platform.” The community leader also shared that after getting involved with the Unified Dashboard, she decided to take a specialization course in Scientific and Technological Information at Fiocruz. “It was a game-changer amid the chaos,” she says.

The Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard covers 71% of Rio’s favelas. So far, 355 communities are accounted for across the region. By July of this year, when the project turns two, the number of communities covered should be even higher. This period will also be one of change for the Dashboard. With the expectation of the pandemic’s daily impact subsiding in the coming months, participating collectives and leaders have decided on their next steps. The plan is to continue research but taking other matters into account. Theresa Williamson, executive director of Catalytic Communities, the nonprofit organization that manages the Dashboard, reveals that energy and water justice and security in favelas will be the central themes this year. “Starting in March, we will carry out a six-month course training 45 leaders and youth from 15 favelas in data collection, identifying the importance of these issues in their communities, which elements they want to study, and how to analyze and report on them,” she explains.

In the meantime, the Unified Dashboard continues to record Covid-19 cases whenever possible, since data were not able to be reported properly during the blackout. Williamson explains that in the beginning, data was sought “door to door” by favela collectives but that, over time, information made available on public platforms began to be utilized, especially as community groups were required to respond to growing hunger in their neighborhoods and so could not afford to collect regular data. “Although favelas are not well covered by the State, we managed to come up with a research methodology based on areas of influence by Zip Code.” Williamson is referring to a technique developed by Fiocruz’s Renata Gracie for use by the Unified Dashboard. With it, zip codes close to each favela are identified and later used to notify cases in these territories. However, this work cannot be done without access to public data.

Following the blackout, a simple analysis of data from the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard provides an estimate of lives saved in favelas by vaccinations and the less deadly nature of Omicron: 1,265 people are still with us who we would otherwise have lost.

Voz das Comunidades also notifies Covid-19 cases through its Covid-19 in Favelas dashboard. The page was launched in April 2020, using data from health centers and family clinics, city and state governments as sources. With this tool, the news outlet is able to alert favela residents about the current context. This is yet another initiative by a favela organization that emerged to show the reality of the pandemic in these territories, normally left out of official bulletins. Melissa Cannabrava, communications coordinator for Voz das Comunidades, explained why the dashboard was created. “[The dashboard came about] because of the inconsistencies we kept finding in the City’s dashboard. Communities were not being properly mapped.”

For initiatives that work collecting data and supporting communities, the effects of the pandemic go beyond health care. The health crisis exacerbated pre-existing social problems in these territories, in addition to triggering others. Fighting hunger has become a common, urgent goal for favela organizations during the pandemic. Major campaigns to collect and deliver food had favela residents themselves as protagonists, organized into collectives and work fronts, such as the Maré Mobilization Front, Jaca Against Corona, and many others. At the end of last year, Voz das Comunidades distributed baskets of basic foodstuffs as part of the sixteenth edition of the “For a Better Christmas” campaign. In this action alone, some 40 tons of food were delivered.

Without support and due recognition from society and the public spheres to these organizations, it will not be possible to maintain so many work fronts. Support for community organizations is essential for fighting Covid-19 in favelas and peripheries, given the insufficiency of concrete public actions and policies for these territories.

About the author: Victória Henrique is a reporter with community newspaper Voz das Comunidades, currently studying Journalism at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). She previously collaborated with Notícia Preta, an anti-racist journalism portal, and produced and presented a Mídia Ninja education program on YouTube, in addition to being a columnist for the outlet. Among the projects she took on at UFF, Henrique worked as a photography instructor at a Morro da Providência favela cultural center.

*RioOnWatch and the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard are Catalytic Communities initiatives.