This article is part of RioOnWatch’s #VoicesFromSocialMedia series, which compiles perspectives posted on social media by favela residents and activists about events and societal themes that arise.

For the Jacarezinho favela, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, the start of 2022 did not feel like a new year. Once again, residents were faced with the flawed “retaking of the territory” narrative promoted by Governor Cláudio Castro, the Civil Police and the Military Police. Eight months after the Jacarezinho Massacre, which had taken place on May 6, 2021—also defended by the governor—the favela, still recovering and mourning its 28 deaths, began witnessing a new cycle of terror on January 19, at 5am: the so-called Integrated City Program. Once more, fear reached the alleys of Jacarezinho, embodied by covered faces and rifles in hands.

After only three weeks of the program, reports of human rights violations were already abound. Once again, residents saw old solutions being sold as new ones. Once again, it is necessary to repeat that there is no integrated city without rights.

O Governo do Estado inicia uma retomada de território na comunidade do Jacarezinho. Comunidades que estão no entorno também serão ocupadas, como a do Manguinhos, Bandeira II e Conjunto Morar Carioca. Equipes do #COE, da #CPP e de batalhões da capital estão atuando no local. pic.twitter.com/0YURTawAxj

— @pmerj (@PMERJ) January 19, 2022

The State Government initiated a retaking of territory in the community of Jacarezinho. Surrounding communities, such as Manguinhos, Bandeira II, and Conjunto Morar Carioca will also be occupied. Teams from the #COE, #CPP and battalions from the capital are taking action in the area.

Caption on photo: Integrated Operation

State Secretary of Military Police

Integrated City Program occupations are taking place even while the ADPF of the Favelas is in effect, a Supreme Court ruling which prohibits police operations during the pandemic except in extraordinary cases and which dictates that in such cases, they must always be carried out in coordination with the Public Prosecutor’s Office. With disregard for the ruling, Integrated City was announced as a permanent occupation policy, not as an exception. Thus, a specter of illegality hangs over the program from its inception. In addition, the Integrated City Program has an extremely low level of trust among residents, a population jaded by the politics of fatigue.

Although the invasion began on January 19, the governor announced that he would only divulge the program’s details on January 22—the fourth day of its operations. This caused distrust and left the impression that the State was improvising its plans, including from a budgetary perspective. These concerns were echoed by the traditional media, which promptly dubbed Castro’s actions as the New Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) and UPP 2.0; these refer to a law enforcement program initiated in Rio in late 2008, which aimed to install police units in favelas to eventually pave the way for infrastructure and social programs but was criticized for ongoing police violence and glaring human rights violations, ultimately failing on the promise of delivering peace to communities. The governor tried to differentiate the projects, but this remained unconvincing. It is the same old criminalization of poverty, territories, and their residents.

Estamos no terceiro dia de estabilização do Jacarezinho. Diante do prejuízo que uma ação dessa traz para o tráfico, era esperada uma reação dos criminosos, com a manipulação de parte da população. Os moradores de bem querem e apoiam a entrada do Estado, com serviços e segurança.

— Cláudio Castro (@claudiocastroRJ) January 22, 2022

We are on the third day of Jacarezinho’s stabilization. Considering the damage that such an action can bring to trafficking, a reaction from criminals was expected, manipulating part of the population. The good residents want and support the entry of the State, with services and security. — Governor Cláudio Castro

The Official Narrative

According to the government, the Integrated City Program—which in addition to entering Jacarezinho also occupied Muzema, a community exploited by the militia in Rio’s West Zone—was given an initial investment of nearly R$500 million (US$107 million) in Jacarezinho focused on six axes: social, infrastructure, transparency, economic, dialogue and governance, and security. Some actions on these axes were planned for the beginning of the program, such as: the the Women’s Advancement Program, which is planned to provide resources and monetary incentives for 2,000 women-headed households from 16 to 30 years of age from Jacarezinho and Muzema such as classes and R$300 (~US$60) monthly allowance payments; the Living Well Program, which provides legal assistance in the social security area, digital inclusion, and physical and mental care for the elderly; and the distribution of vouchers to purchase gas cylinders from legal suppliers. Revitalization work on the Luiz Carlos da Vila School and the Youth Reference Center are also underway.

Also promised was a new unit of Rio’s public technical schools—known as FAETEC—along with the renovation of the Parque Manguinhos Library and two public housing developments—one on Avenida Dom Hélder Câmara and one on Conjunto dos Ex-Combatentes—as well as the construction of 765 properties through the Our Home Program. Simultaneously, residents that live in irregular housing situations and without sanitation systems are being registered. Castro promises actions on the Jacaré and Salgado Rivers: micro-drainage, cleaning, dredging, and debris removal. The project would include sanitation works even inside the homes of residents: “The goal is, by the end of the year, to not have a single home without a bathroom in Jacarezinho and Muzema,” said the governor.

These works could lead to the removal of 800 families living along Jacarezinho’s river banks, without any community discussions held, without a publicized project, and without a compensation and resettlement system for affected residents. These removal works are estimated to cost around R$47 million (~US$9.5 million) and will begin in the second half of 2022. According to INEA (Rio de Janeiro State Environmental Institute), the Program includes the canalization of the Salgado River and the upgrading of its surrounding areas with sidewalks, pavement, bicycle paths and leisure areas.

The construction of new public facilities has also been planned: a hospital, local battalion of the Military Police, leisure areas, centers for citizens’ assistance and a farmers’ market. However, this will require the expropriation of the old General Electric factory in Jacarezinho, valued at R$4.6 million (US$936,000).

According to Castro, unlike the UPPs, the Integrated City Program is not just a police occupation but rather a joint work of social actions. For researchers like Carlos Henrique Aguiar Serra, a political scientist and professor at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), it is a repackaging of the UPP: “The Integrated City Program is hardly groundbreaking. It has huge similarities with other programs that no longer have the appeal they once had, such as the UPPs. It is pointless for the governor’s rhetoric to say that it is not a pacification program, as if he wanted to differentiate himself from the UPPs. The state’s public security policy continues to be based on the militarization of public security and the perspective of war and the enemy. And this dual perspective prevails.”

The installation of a video surveillance system with 22 facial recognition cameras placed at key points within the favela was also announced. The cameras’ features include: facial detection, license plate detection, ability to count people, and color image detection in low light environments. The monitoring center will be located in the Cidade da Polícia, the city’s center for police operations for specialized units, close to Jacarezinho.

“’Integrated City’ is a nice title, but in reality, it is a militarization of the city and there is nothing about it that is integrated. It’s extremely empty rhetoric… a tragedy that repeats itself in the daily lives of the lower classes.” — Carlos Henrique Aguiar Serra

The Dangers of Facial Recognition for Favelas

Previous attempts at implementing facial recognition in Brazil have not produced good results. As pointed out by Pablo Nunes, who has a PhD in political science and coordinates CESeC’s Panopticon—Facial Recognition Monitor in Brazil: “In the case of Rio de Janeiro’s pilot project, we didn’t find relevant impacts on crime metrics. On the contrary, virtually all major crime rates increased during the use of facial recognition technology in Copacabana. This shows that these cameras have little impact on reducing crime.”

The Copacabana pilot project is not an isolated case of facial recognition technology’s ineffectiveness in Brazil. Nunes analyzes the effects resulting from this technology: “In the Brazilian context, we’ve had an advancement in facial recognition, especially starting in 2019, with Bahia being the state where this technology has been operating the longest time in the country. And since it’s been in operation the longest, it is also where the number of arrests is the highest: there are now over 200 arrests made using facial recognition. In light of these arrests, we started to catalog the cases and ended 2019 with 184 people arrested. In the cases where information was available, 90% of those arrested were black people imprisoned for nonviolent crimes, such as theft and traffic of small amounts of drugs.”

The prevalence of black prisoners exposes social oppression translated into binary codes and algorithms. Facial recognition is not a neutral technology. It has racial, social, and gender biases.

Nunes outlined some of these dangers for the Brazilian context:

“These cameras… we know how many problems they create, especially for the black population that is much more likely to be confused for one another by these cameras than white men are, who are the portion of the population that have better results in terms of recognition through algorithms. This has an important impact on people’s lives in terms of human rights violations. Here, in Rio de Janeiro, on the second day of the [Copacabana] pilot project, in 2019, someone was wrongfully arrested when, in reality, the person they were looking for had already been arrested four years earlier. Thus, this reveals how much the institution itself is not prepared to deal with this technology.

For favela residents, the State arrives in the form of a rifle and now also in the form of human rights violations through video monitoring. Imagine how much information will be produced by these cameras that record 24 hours a day. And what we don’t discuss is the right to privacy, to protect the personal data of black people living in favelas. It is seemingly positioned as a choice between two worlds: you either accept a public security policy that we’re imposing on you or you choose to protect your personal data. This choice should not exist in a democracy. It is not democratically plausible and acceptable that a portion of the population should have to choose which right they want to protect among those they possess in the Constitution.”

Disintegrated City: Necropolitics and Racism at the Ballot Box

In a gubernatorial administration with an expiration date of eleven months, the inconsistency in adopting a long-term policy—which would propose making structural changes—has been pointed out. A policy of such magnitude, which aims to deeply intervene in a complex situation, should have been developed over months, at various levels of government. However, according to the mayor of Rio, Eduardo Paes, this coordination did not happen.

Fui informado ontem no fim do dia pelo próprio governador. O que não houve foi planejamento prévio com prefeitura. E ressalto que apoio a iniciativa e trabalharemos juntos pelo bem de nossa gente. Só tem é que ter segurança pública. https://t.co/1pD394P8wY

— Eduardo Paes (@eduardopaes) January 19, 2022

I was informed yesterday at the end of the day by the governor himself. What we didn’t have was prior planning with City Hall. And I emphasize that I support the initiative and we will work together for the good of our people. Let’s just have public security. — Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes

For Carlos Henrique Aguiar Serra, this is a program that will not last long due to its vertical nature—disconnected from the territories and ephemeral: “What also draws attention is the electioneering nature of the Program… an attempt to disguise the reality. A short-term, seasonal public policy that will end if the government is not re-elected. This is the difference between an inconsistent and ephemeral public policy and a consistent public policy of the State… [the ephemeral ones] are launched at the mercy of the conjecture, with a range of extremely pragmatic interests and attempting to hide reality. Unfortunately, they reproduce this whole logic of oppression, repression and criminalization, and there is still no prospect of change.”

The Integrated City Program carries the faults of old occupation projects and the continuities of past failures: the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) and the Social UPP; the Detached Units; the Ostensive Police Detachments (DPO); the Community Policing Stations (PPC); the Special Area Police Groups (GPAE), etc. Like all these previous policies, the Integrated City Program is sold as a magic potion.

Many of these policies have been discontinued and weakened over time, such as the UPPs. Others have been almost completely phased out, such as the DPOs and the PPCs. In some cases, these militarized spaces have been taken back and given new meanings by the communities such as the Antares DPO, in the West Zone—which turned into the Mariginow Library, a community library and cultural center—and Vila do João’s PPC, in Complexo da Maré, which became the Residents’ Association. In other instances, even if only in appearance, relics of past policies continue to function in a residual way, such as the Parque União PPC, also in Maré, and the Morro do Barbante DPO, in Ilha do Governador.

“The main thing about this program is not public security,” said Castro. However, experts see the escalation of the war on drugs, militarization and violations committed by police through records of break-ins and home invasions, destruction and theft of property, threats, psychological torture, aggressions against children, animals and adults. Some residents state that even children’s piggy banks were stolen by the Integrated City Program’s police officers.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Captions on original video:

“Integrated City,” the new public security project, has this type of behavior towards the residents of Jacarezinho.

Real images of human right violations towards the residents!!! Absurd!!!

Comment by Monica Cunha: “The public security program that guarantees the least amount of safety to favela residents. It is an absurdity to come home and find your belongings stolen and turned over!!!”

Favela residents have understood for years that they need to prove their innocence. It is necessary to convince the police that their belongings and household items were honestly acquired, even when they are not home. For this reason, when they go out to go to work, residents have been hanging notes on their doors with the intention of explaining their professions to the police and justifying their assets.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Original post by @ajessicalene: URGENT! Jacarezinho residents are writing their professions on their front doors to avoid invasions, raids, and fights caused by the Rio de Janeiro Military Police (PMRJ) Occupation.

While the Federal Police (PF) had to call a locksmith to investigate the corrupted, see below:

“I work as a consultant by day!!! A security guard by night!!!”

Monica Cunha’s post: #Repost @jessicalene with @make_repost

When I read @diaguiar’s report on the reaction of Jacarezinho residents, who now need to declare their professions on their front doors in order to prevent invasions, fights and thefts, I was sure that the favela still hasn’t won.

The occupation in Jacarezinho is creating several issues for the residents. This is not public policy… this is the extermination of our population through institutional violence.

Revolting!!!

#outbolsonaro #outclaudiocastro #jacarezinho #occupationandmakeup #publicpolicies

Despite the occupation starting at 5am, residents had already sensed the siege of the community the night before, without even knowing what was going on. Fear and silence once again took over Jacarezinho. Rodrigo Mondego, the prosecutor for the Brazilian Bar Association, Rio de Janeiro Chapter (OAB/RJ) Human Rights Commission, reported what he witnessed during a visit to the favela:

“We heard [about the siege to Jacarezinho] the night before the occupation. There was a fear among the community, local leaders and social movements of some massacre, some type of violence. Nobody from the community knew what that siege was about. Only the next day, with the occupation, did we come to know about the Integrated City project.

Several reports reached us: home invasions and burglaries perpetrated by military police, for example. On the Saturday following the invasion [January 22] we went there—the Rio de Janeiro Chapter of the Brazilian Bar Association and the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) Human Rights Commissions, along with the Ombudsman of the Public Defender’s Office—to hear from the residents. In the middle of our visit, we witnessed some houses that had been invaded by the police [minutes earlier]. One impactful case was that of a man who sells cheese on the beach and who had been working while his house was invaded. They stole several things from the house, among them a jar of coins where he kept his savings.

We then followed up on a case of torture of a law student who had his house invaded. The house was even used as a law office, with a room in the house for a lawyer to do his work.”

Following the occupation, Special Operations Battalion (BOPE) officers hung their flag on one of the houses in Jacarezinho pic.twitter.com/dX7yCCLzv7

— Favela Caiu na Rede RJ (@FCNRRJ) January 26, 2022

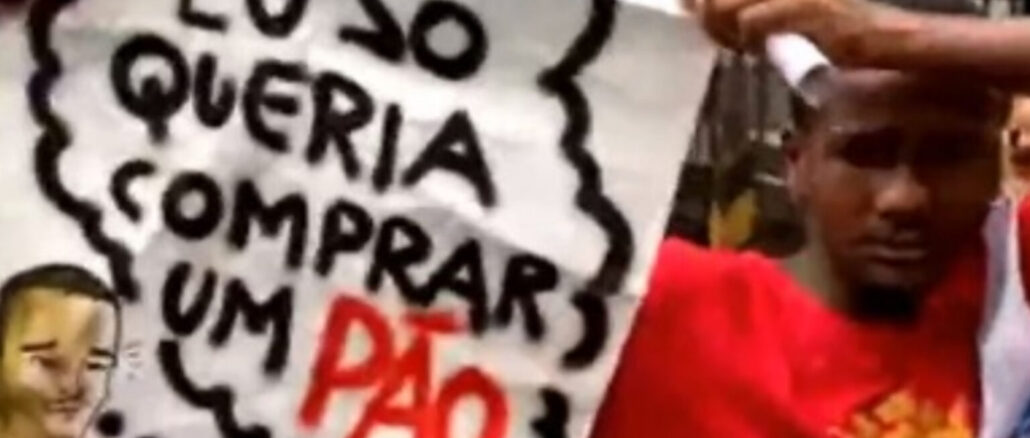

Another emblematic fact of the type of policing that the State offers favelas happened in Jacarezinho on February 6: the arbitrary arrest of Yago Corrêa de Souza. It was Sunday, and the 21-year-old man had gone to the bakery to buy bread for a barbecue. As he was leaving the bakery, he was surprised by Integrated City Program police officers who arrested him for drug trafficking and association with trafficking and taken to the José Frederico Marques Prison in Benfica. A blatant instance of abuse by the police. Police Chief José Borba Carregosa, from the Praça da Bandeira 19th Police Department, who led the investigations on the case, said that de Souza “was in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

On February 8—two days after the arrest—at the custody hearing, the judge had no evidence to keep him in prison and granted de Souza a provisional release pending trial. Therefore, de Souza will continue going through legal proceedings while free, after being in prison for two days for buying bread in the favela where he lives. [Update: Judge Gisele Guida de Faria closed the case against de Souza in late February, revoked all proceedings and demanded that all mention of the case be expunged from his criminal record.]

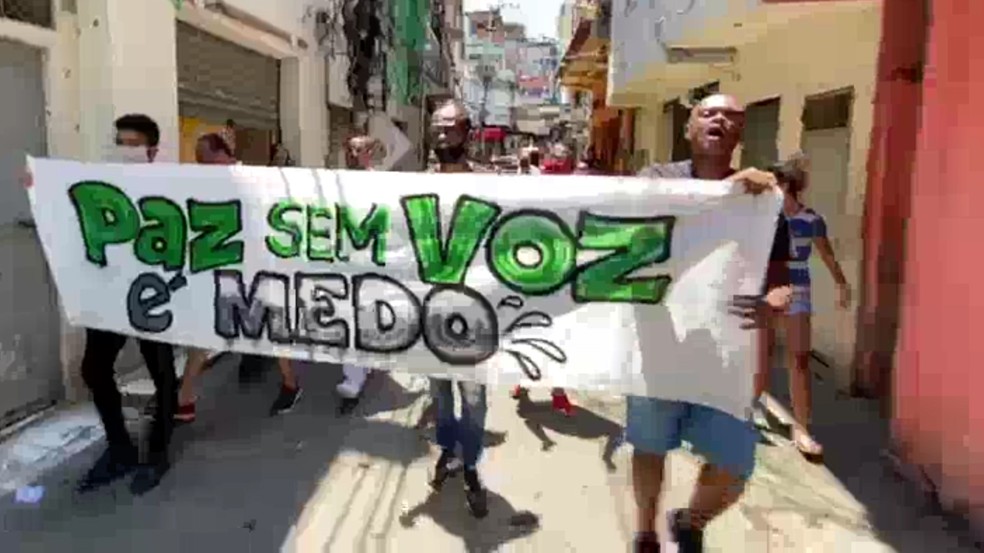

Shortly after de Souza’s release on February 10, Integrated City Program police officers reinforced necropolitics, this time killing a resident of Jacarezinho. João Carlos Sordeiro Lourenço, 23, was wanted for homicide, but instead of being arrested and tried in court, he was executed by police. This murder caused outrage and protests from residents on Avenida Dom Hélder Câmara, one of the North Zone’s main avenues.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Jacarezinho residents are protesting after the death of a person in the favela. Is this how the Integrated City project is going to function in Jacarezinho? On Sunday, a young man was arrested buying bread and today a dead person in the community. This project is nothing more than the extermination of those who live and survive in the favelas. Stop genocidal actions!

The Militianization of Public Security

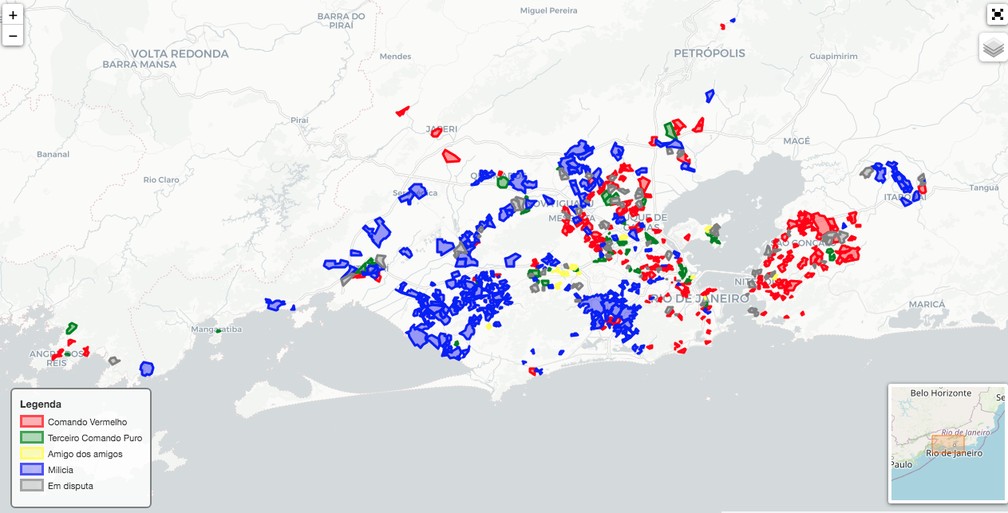

At the same time that troops were entering Jacarezinho, they were also invading Muzema, a community exploited by off-duty security personnel-comprised militia in the West Zone. Today, it is such militias that territorially control most of the favelas and peripheries in Rio and Greater Rio. According to the Rio de Janeiro Armed Groups Map, militias already illegally occupy and exploit 57% of the territory of the city of Rio. However, historically, they have not been a priority target of police confrontation and occupation policies. Many claim that recent government administrations have been complacent with the militia.

Militias have been deforesting native forest and environmental protection areas and—through violence—manage real estate speculation in the West and North Zones and Baixada Fluminense. The governor promised that with the legalization and titling of properties, in addition to credit lines worth R$30 million (US$6.2 million) for residents, the local militia gang will lose a significant part of the economic power it derives from real estate speculation in Muzema and loan-sharking. However, Serra concludes that these measures might end up benefiting the militia: “In Muzema, there is negotiation [between the government and the militia]. Recent government administrations have always colluded and there is basically a militianization of public security… It is pointless for the governor to announce that he’s going to grant titles to properties, because these actually belong to the militia. Public security policies in Rio de Janeiro combine militarization and militianization, which coordinate and practically merge.”

These militia gangs also work by charging security fees and controlling telephone, cable TV, and Internet services, including hijacking antennas from formal service providers, cooking gas, drug trafficking, cigarette counterfeiting and smuggling, slot machines, illegal mining, illegal sand extraction, and fuel theft, among others. At the end of 2021, even a “pig tax” began being charged in Favela do Rola, dominated by the militia: R$5 (~U$1) per week for each pig being bred. If the resident doesn’t pay for two consecutive weeks, the animal is confiscated and used by militia members for their barbecue.

Na área da Muzema, que sofre influência de milícias, as ações vão focar no combate ao comércio ilegal de gás de cozinha, crimes ambientais e construções irregulares. A Secretaria de Estado de Polícia Civil também atua em conjunto com a SEPM nestas ações.#PMERJ#CombatendoMilícia pic.twitter.com/9myxtQWBTT

— @pmerj (@PMERJ) January 19, 2022

In the area of Muzema, under the influence of the militia, actions are going to focus on the fight against the illegal sale of cooking gas, environmental crimes, and irregular constructions. The State Secretary of Civil Police is going to act with the State Secretary of Military Police on these initiatives. — Rio de Janeiro Military Police

The Integrated City Program’s lack of transparency and dialogue are structural failures. Castro promised to create community councils with members of the government and representatives of the community. However, residents complain that they have only had one meeting with the government about the project, just three days after the occupation and after a lot of public pressure. The favela remains unheard, afraid.