This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

Funk first became a hit in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in 1980, amid the country’s re-democratization, the economic crisis and other cruel outcomes for the working class. Unknown up to that stage, a virus was causing a health crisis: HIV. The HIV/AIDS epidemic killed millions all over the world and hit the poor and those living in social vulnerability the hardest. This article is dedicated to the funk movement, that dealt with this and various other crises with no media coverage, support from large institutions or governments.

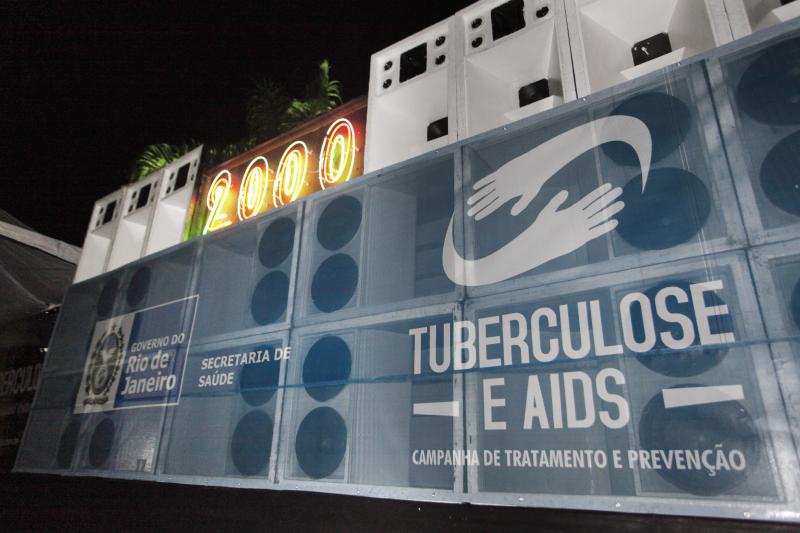

Funk is a great example of the “by us for us” strategy employed by Rio’s favelas and urban peripheries. In many crisis situations, funk is a social, economic and humanitarian tool for these territories. Throughout the years, awareness campaigns, balls organized for HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis prevention, activities to fight dengue outbreaks, and several other crucial mobilizations were led by the funk movement.

In a documentary about carioca funk, Romulo Costa, founder of funk producer and recording label Furacão 2000, recalls the distribution of condoms, activities to eradicate dengue mosquito breeding sites and the organic way in which funk raised awareness in his community. According to him, “that’s why funk, independent of the style, gets the message across; because it was born of the need to strengthen communities.”

This is an idea shared by DJ Marlboro, another precursor of funk in Rio:

“In Brazil, funk plays the social role of being able to glue back the divided city; it’s the funk movement that patches up the city that’s been cracked and broken by the scars of racism and classism. Funk works like an NGO that has no intention of being one.” — DJ Marlboro

Funk is the peripheral cultural movement that actively protests against police violence, preaching peace, education and opportunities for leisure for poor children. Besides the musical aspect, funk gained an important role denouncing the inefficiency of public policies in promoting collective wellbeing. Particularly when it comes to public security, as in the case of Cidinho and Doca’s tune, Não me Bate Doutor [Don’t Beat me Up, Sir]:

According to DJ Marlboro, the educational system in Brazil does not work for the favela resident. Often, the only alternative opportunity to drug trafficking is funk. The favela produces professionals, athletes, musicians, dancers, but without the necessary investment, all of society loses part of this favela power.

“Everything that doesn’t go commercial, dies. So, nowadays, we see a funk scene that’s dictated by the music industry, leading many MCs to adapt their styles to current trends. But funk itself will always be conscious and, even with commercialization, it still helps many families in the favela.” — DJ Marlboro

At the end of the 1980s, the popularity of funk balls in the favelas and peripheries drew millions of people into crowded stadiums and warehouses across Brazil. The Brazilian elite started marginalizing these majority black and poor spaces. Indeed, it reissued a longstanding narrative of criminalization of these spaces, their culture and music. Today, funk is criminalized like samba was in the past. Stemming from this marginalization, funk became more and more socially aware. Songs about social justice, dignity for favela residents and many other themes of protest have taken the scene.

Instead of investing in funk as public policy, the Brazilian State contributed to building an image of it that is linked to crime and vagrancy. According to historian Gabriel Siqueira, funk is important for creating jobs inside and outside favela territories.

“If a funk ball attracts over 2,000 people per night, it employs over 200 people who are working and generating income for their community.” — Gabriel Siqueira

In addition to its economic turnover, carioca funk also has a strong humanitarian element to it. It is common to find in funk lyrics protests against the legalization of weapons, against gang brawls at funk balls and even for disease prevention. “Funk artists like Lacraia and MC Serginho had a fundamental role in the fight against HIV/AIDS in the favelas, handing out condoms and sending out the ‘straight talk’ on prevention,” says Siqueira.

The are many examples, like the blood drive campaigns that funkeiros mobilize all over town. One of these is called Good Blood Funkeiro, that organizes caravans for the HEMORIO Blood Donation Network. From the start, funk mobilized fans of the genre to save lives, through solidarity. Events such as the clothes ball, the toy ball, the school supplies ball, as well as the food drive funk balls and other initiatives demonstrate the commitment of the funk movement to human rights.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

On the banner: Do good unto others, regardless of who they may be. Give blood, give life.

Instagram publication: Our banner at the Irajá ball.

This humanitarian tradition of funk is a legacy for the new generations. Many MCs and cultural producers, people who profit from the musical genre, invest in their communities supplying historical demands that are neglected by the State. DJ Rennan da Penha, for example, distributed full school supplies kits to the children of Complexo da Penha and Complexo do Alemão. Singers like Ludmilla and MC Poze do Rodo make donations and help thousands of people from the success they have achieved with funk.

During the coronavirus pandemic, funk and social movements were essential for the survival of black and peripheral bodies. It was through coordinated actions with residents’ associations and civil society organizations that favelas were made aware of the risk of coronavirus contagion.

The funk movement clearly has the potential to be recognized and supported through public policy. With public investment, it would be able to advocate culturally for the social and humanitarian development of favelas and peripheries. Brazilian funk is an internationally known rhythm but prejudice and stigma rooted in Brazil prevent its institutionalization as an official mechanism against social vulnerability.

About the author: Emerson Caetano is a resident of Greater Rio’s Nova Iguaçu municipality, a peace activist and founder of NENRI – Center for Black Students of International Relations. A social entrepreneur for racial equality and an international decolonial analyst, Caetano is a UN Fellow of the International Decade for People of African Descent and has experience as a speaker and activist in over nine countries.