This is our latest article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on climate impacts and affirmative action in the favelas for RioOnWatch. It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

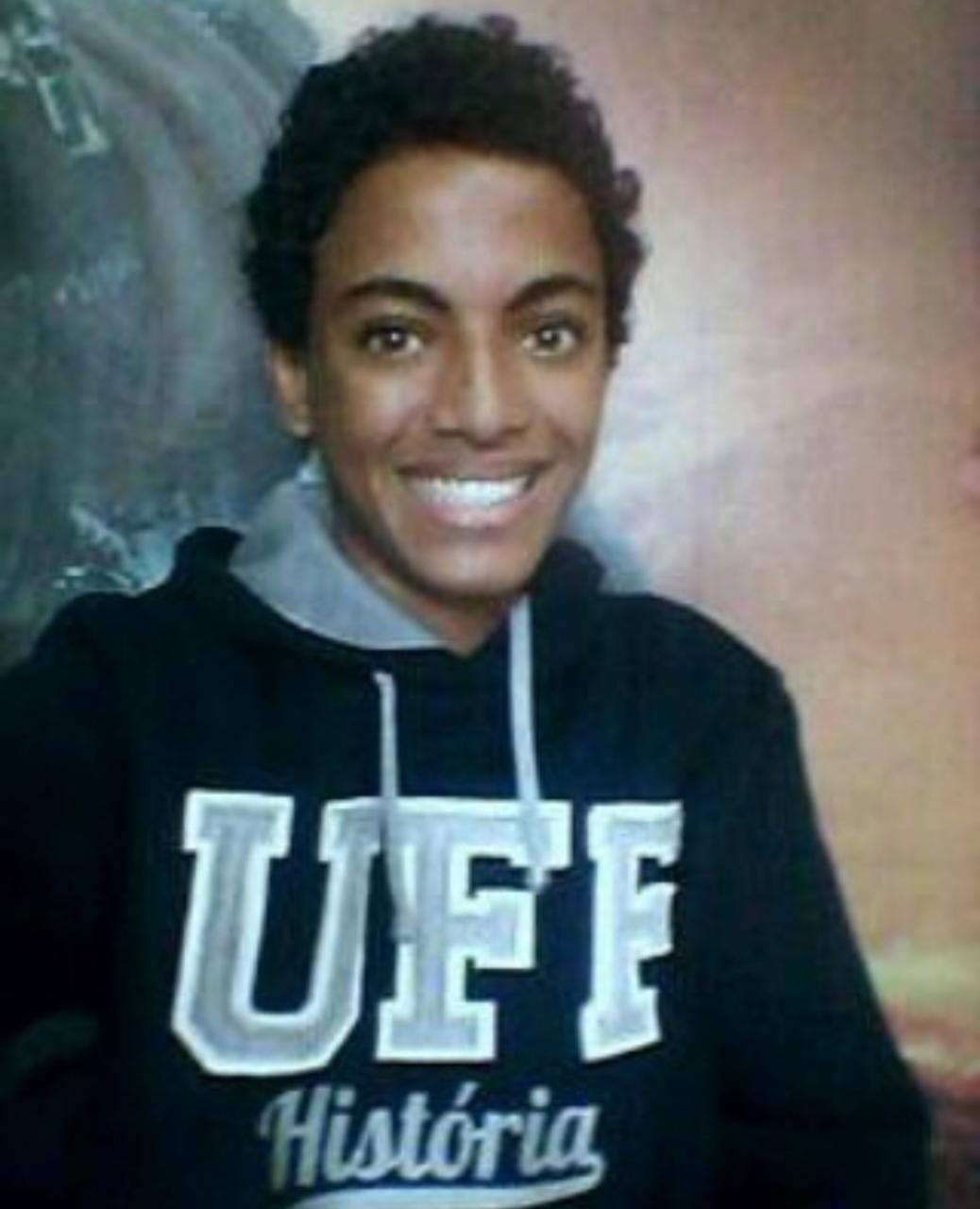

Born in the Jabour neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, Rafael Silva Santana Barbosa lives in nearby Bangu where he wants to change his community for the better. Having recently graduated from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) with a degree in history, Barbosa reflects on his family’s conditions as compared to those for whom his neighborhood is named. This profile also covers Barbosa’s path and the role of education in his life. Get to know the profiles of other affirmative action beneficiaries published on RioOnWatch here.

There is a double standard when it comes to access to education in Brazil. Intact, easy, and comfortable, access to education is served on a platter for some. We can compare the path of these students with that of high-performance athletes, for example. Both have a wide range of coaches and physical trainers available to them from an early age. These are the students pictured on billboards that advertise private schools, flaunting their first pick of this or that university, always with their race and social class very well defined.

On the opposite end are young people like Rafael Silva Santana Barbosa, 26, a historian and educator who graduated from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), one of the first and most important universities in the country to adopt an affirmative action quota system in 2004. At that time, the policy reserved vacancies for former public school students, people with disabilities, and people who declare themselves black.

Anyone who thinks that this meritocratic validation of the dominant classes in Brazil is new would be wrong. Records of old newspapers from the beginning of the 19th century include editorials that explicitly list the students that passed university entrance exams, semester exams, and those graduating. Today, their last names might very well be the name of the street where we live, the neighborhood where we were born, or even the politician in charge of our state.

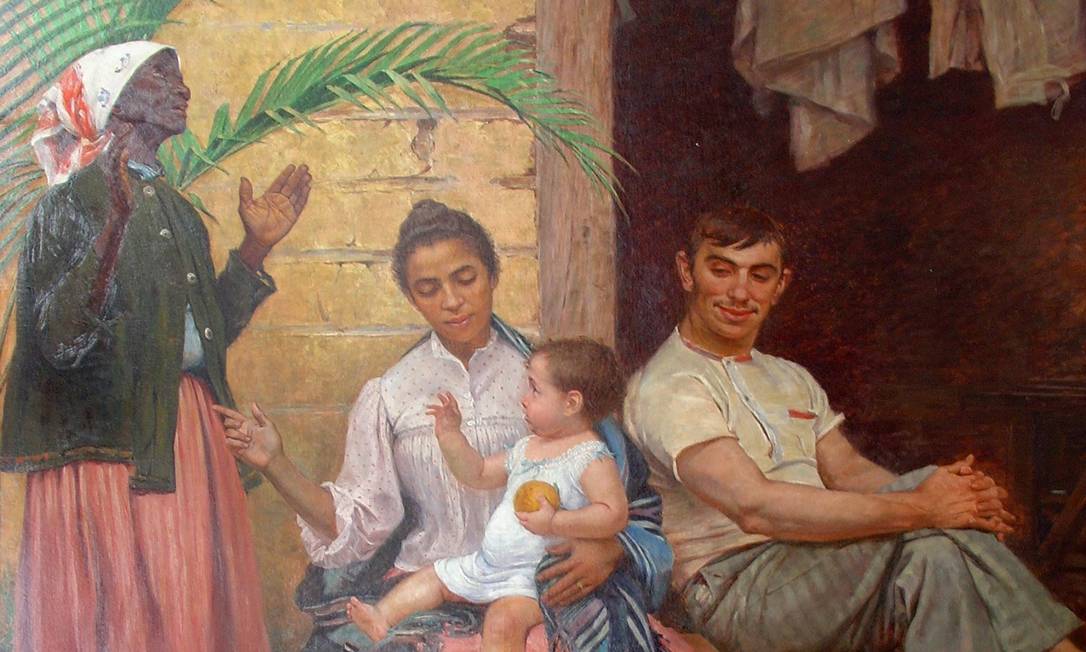

Barbosa was born in Jabour and raised in Bangu, both neighborhoods in the West Zone of Rio. The neighborhood where he was born pays tribute to Abrahão Jabour, a Lebanese immigrant to Brazil born in 1884 who achieved great financial success with the cultivation and exportation of rice and coffee in the country, besides countless real estate and industrial ventures. These achievements were partly the result of myriad government licenses granted to the immigrants of the time, based on a campaign to whiten the population following the abolition of slavery. European, Syrian, Lebanese, and Japanese migrants entered the Brazilian workforce in a partnership system. Farmers financed their immigration process while formerly enslaved people were pushed to the margins. The idea was that, besides serving as labor, these people would help enhance the whitening of the Brazilian population in a few generations. The aim was to make Brazil a country with a white majority and thus achieve a model of civilization like that of Europe.

The arrival of the Syrian and Lebanese communities was a bit different. While many European migrants came to work in agriculture, the Lebanese often worked in industry and trade, leading to significant wealth increases over generations.

Today, while 2.9 million Brazilians, or 1.5% of the population, are of Lebanese origin, 8% of parliamentarians in Brazil’s National Congress are of Lebanese origin. The Lebanese-Brazilian population makes up the largest component (27%) of the 7% of Brazilians of Arabic origin. Their high representation in politics is influenced by the economic success and investment in education by Arab-descended families in Brazil. Are you familiar with last names like Temer, Kassab, Maluf, Boulos, and Haddad?

Descendants of Lebanese immigrants to Brazil are socially perceived as white and do not experience racism, unlike Arab immigrants to Europe or the United States. This has to do with the racialization process in Brazil, that considers Middle Eastern immigrants and any non-black people as white. Furthermore, the Syrian and Lebanese immigrants to Brazil were mostly Christian—members of Eastern-rite Catholic Churches such as the Maronite Church, the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Syriac Catholic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Coptic Orthodox Church, and others—which further increased their acceptance by local society. Socially and economically successful, they occupied a significant part of Brazilian politics.

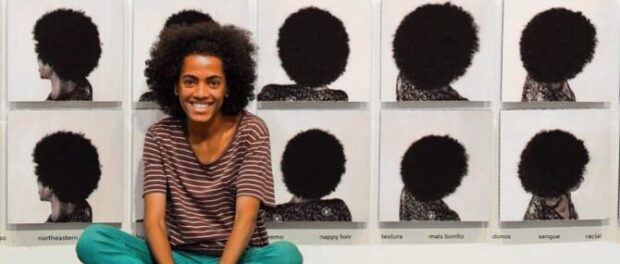

Syrian and Lebanese representation is opposite to the phenomenon of under-representation of black people in Brazilian politics. While Afro-Brazilians comprise 54% of the Brazilian population, we only make up 17.8% of the National Congress. To this day, the long process of slavery structures the extreme inequalities experienced by us, black people. Without the right to education and social mobility, much less the myriad government licenses and incentives other groups were met with upon arrival to Brazil, black people remain trapped in social captivity.

Strategies, Distance, and the Dream of a College Degree

“It was common to come home early, to not have classes, and stay at school doing nothing because teachers didn’t show up.” — Rafael Silva Santana Barbosa

Testimonies like the one given by Barbosa are intrinsic to our daily lives. They are commonplace and ordinary, the rumors of a “free school period” that take over the corridors of the public schools of favelas and peripheral neighborhoods throughout Brazil. The frenzy of teenage innocence. A school absence celebrated there and then but that is deeply felt years later in life. Not having classes in a specific subject is one of the biggest factors in the school flight process. In Barbosa’s case, it was a complicating factor for him to retain what he was learning in certain undergraduate subjects that required a more solid school base. He wanted to have those classes, but they were neither offered in full, nor at the right moment.

“I only had history in high school; I never had it as an elementary school subject. So, when I took history in college, I was at a huge disadvantage. There was a lot of basic content that I didn’t know. But since the professors made me like what I was learning, I was able to overcome those barriers at the university level.” — Rafael Silva Santana Barbosa

A public policy of socioeconomic mobility like affirmative action cannot and should not suppress other State-sponsored actions. Basic education needs equal attention and management. There is a common notion, an empty argument, that if the quality of elementary education improved there would be no need for affirmative action policies. However, even if both policies were being fully carried out in Brazil, they would still be insufficient to solve the country’s educational deficit. A reflection of over three centuries of enslavement of Africans and Afro-Brazilians, the unequal access to education exemplifies the racist structure of Brazilian society.

His parents’ efforts and support enabled Barbosa and his brother to attend a paid college entrance exam preparatory course. Although his parents did everything they could, the money was only enough for the beginning of the course. Barbosa told us that even after leaving the course, the debt they were left with was so big that it was only paid when both he and his brother were already in college. In 2014, after a few months of study, Barbosa got a sufficient score and was admitted to college through the affirmative action quota system. In a third round of acceptances, he was notified of his admission to the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) at its Campos dos Goytacazes campus, a city to the north of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro.

His parents’ efforts and support enabled Barbosa and his brother to attend a paid college entrance exam preparatory course. Although his parents did everything they could, the money was only enough for the beginning of the course. Barbosa told us that even after leaving the course, the debt they were left with was so big that it was only paid when both he and his brother were already in college. In 2014, after a few months of study, Barbosa got a sufficient score and was admitted to college through the affirmative action quota system. In a third round of acceptances, he was notified of his admission to the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) at its Campos dos Goytacazes campus, a city to the north of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro.

It is worth mentioning that Barbosa was only made aware of the possibility of attending university through the affirmative action quota system because his college prep exam course teachers pointed it out to their students. This possibility was not even mentioned at his previous schools where he’d gone for elementary and high school. It was thanks to these teachers that his journey began at UFF.

Over 180 miles separated his house in Bangu and his dream of studying history at the university level. His wish of giving back to his community made him dive wholeheartedly into the unknown. Barbosa studied a full semester at the Campo dos Goytacazes campus before requesting a transfer to the nearer UFF campus in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across Guanabara Bay. Although closer to home, his new campus was still almost 60km away. This meant over three and a half hours on public transit every day just to get to school, without taking into account the expenses with food and transportation between municipalities—the highest rates in the metropolitan region. This battle ended in 2017, when Barbosa was able to transfer to the State University of Rio de Janeiro, closer to home, where he finished his undergraduate studies in 2021.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

“Today it took me almost four hours to get to school and I only had two and a half hours of classes, you know what I’m saying? Yeah, but I’ll just take a deep breath and keep going (God’s good, not evil). The distance has been a problem, except that in this case it wasn’t just the distance (though I’d already been stuck six hours in that itinerary alone). Another complex factor is the money spent because over 30 reais a day on transportation is a lot (I only got a break when my bus pass had credit due to the integration systems); I often got to school psychologically exhausted. Except that today [thank God] my transfer to a university closer to here was accepted and fares are much cheaper. On the other hand, it might seem like madness since classes that I’ve already taken will not be accepted. But I don’t see a problem, since independent of all of this I’m going and I’m going to do it because I value my sanity.”

Barbosa is an education enthusiast and believes it can make a difference in the lives of people, especially those who live in the city’s peripheries. He participated on UERJ’s educational team for three years, besides also being a mediator of cultural exhibits and a volunteer researcher at the Vasco da Gama Rowing Club, a traditional Rio de Janeiro soccer team’s rowing club, and at the Afro Digital Museum. The historian currently teaches and tries to promote cultural projects that have been suspended in the region where he lives, the West Zone. His main objective is that peripheral people not only get into university but genuinely feel a part of it.

“Getting my college degree was an enormous joy and a great relief because it took me almost eight years to finish my undergraduate course. I felt very welcomed at UERJ.” — Rafael Silva Santana Barbosa

About the author: Cleyton Santanna holds degrees in journalism and screenwriting from UFRRJ and the CriaAtivo Film School. He uses his YouTube channel to address oddities, ancestry, and Afro-Brazilian culture. In 2017, he produced two documentaries: “Entre Negros” (Between Blacks) and “Tudo Vai Ficar Bem” (Everything is Gonna Be OK), and was recognized as a screenwriter in 2018 by the Creative Economy Network for the short “Vandinho.” He is currently a communicator for the Museum of Tomorrow and hosts the Influência Negra podcast.