Brazil’s 20th National Museum Week, which took place from May 16-22, 2022, introduced the topic The Power of Museums. This article reports on how this power is being realized by some of Rio de Janeiro’s favela museums.

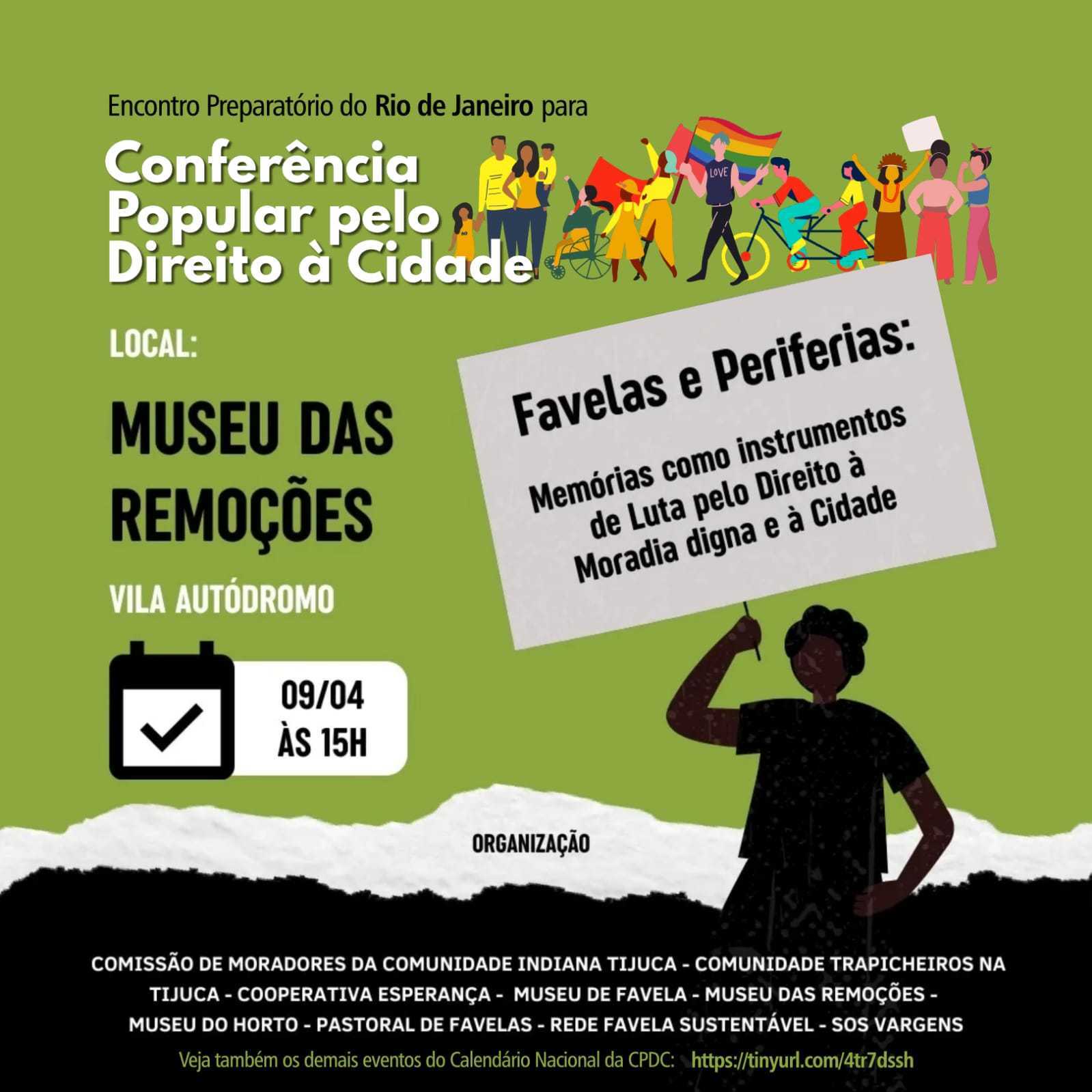

As part of the preparatory activities for the Popular Conference on the Right to the City, community leaders, technical allies and public agents met in early April in the community of Vila Autódromo, host to the Evictions Museum, to discuss the theme “Favelas and Peripheries: Memories as Instruments of Struggle for the Right to Dignified Housing and to the City.” The event was organized by members of the Residents’ Commission of Tijuca’s Indiana Community, the Trapicheiros Community, the Esperança Cooperative, the Favela Museum (MUF), Evictions Museum, Horto Museum, the Favelas Pastoral Committee, the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN), and SOS Vargens. Among the participations, a few presentations stood out such as those of: Maria da Penha Macena, from Vila Autódromo and the Evictions Museum; Neide Mattos, from the Esperança Cooperative; Marcello Deodoro, member of the Indiana community residents’ commission; Ailton Lopes, second secretary of the Trapicheiros community; Emília, member of the Horto Residents’ Association and co-founder of the Horto Museum; and Márcia Souza, from the City Favela and Heritage Forum and founder of the Favela Museum.

Macena launched the event with a compelling talk on how peripheral and favela residents need to be respected: “All of us have a right to the city. We are the ones who built this city but are often violated within it. And that’s what this meeting is for today, so we can talk a little bit about this lack of respect… If people figured out how strong they are, we would have a country full of potential.”

Roundtable Introduction Discusses Memory, Museums and Evictions

Following the opening, the event continued with an exchange of experiences between community representatives about the history of their communities, the main challenges faced and what solutions they found to overcome these situations. Regarding community museums and the Evictions Museum, Macena added: “community museums, which are created with great difficulty, are not entitled to anything. Every territorial museum was built by us, with our own stories. And we don’t have voices, we don’t have capital. The Evictions Museum, for example, is voluntary. Our work is great, I am very happy to be a part of this museum… But we’d like to know when we will be truly able to have this city represent us, respect us, which is crucial.”

About the Esperança cooperative, Mattos explained the struggle it was to claim the right to housing, the years it took participating in meetings and being at the construction site, building homes in her community: “We’ve been a group for 22 years, a group that started off meeting in the middle of the street, people who needed houses. And from there, together with the National Union for Popular Housing, we started to demand land, to demand resources… We managed to build 70 houses… [The Esperança Cooperative] is a beautiful project in its essence and in its physical aspect.”

Mattos also highlighted the key role of women in the construction of the cooperative: “All of this, mostly, with the labor of women; the group is made up, for the most part, of women. We women have the desire, the need to have our home, our corner. So, when there’s a fight among women, my friend, get out of the way, because women can do a lot.”

Next, Deodoro introduced the Indiana community: “It’s a small community, with approximately 600 houses… In 2012, we had to fight not to be decimated, not to be evicted. Hence, the creation of the Indiana Residents’ Commission, which, along with the Favelas Pastoral Committee, the Popular Council, all the social movements and the Rio de Janeiro State Public Defender’s Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH), mobilized to fight so that we wouldn’t be evicted. And this year, 2022, we are celebrating ten years of resistance.”

Lopes also introduced his community, Trapicheiros: “It’s a century-old community… Starting in 2010, we also went through the same issue, two years before Indiana, facing City Hall wanting to tear down people’s houses… And in 2015-2016 a condominium was built where they devastated a pristine green space… During a public hearing, they called us visual pollution. We resisted. In 2018, we set up our residents’ association. In 2019, we also managed to conquer our AEIS, becoming an Area of Special Social Interest. And now, at the end of 2021, we, the 56 families that make up the community, were granted possession of the land we live on through the Land and Cartography Institute of the State of Rio de Janeiro (ITERJ).”

Lopes also reflects on what it means to be considered an invader: “We have a family that’s been in the territory for four generations. How can we be fourth-generation invaders? My wife’s aunt is 84 years old, she arrived in the community when she was six. So how can you have an invader who’s been [in the territory] for over 70 years?”

Next, Emília introduced the Horto Museum and shared her thoughts on the role of favela residents in the construction of the city: “we are neglected, we are discriminated against by the elite, by the bourgeoisie that forgets—no, it’s not that it forgets—that ignores that this city only exists because it received our heavy contribution to its construction, to its existence.”

Finally, Souza, from the Favela Museum, an open-air museum in Cantagalo, Pavão-Pavãozinho, shared some of the history of how the museum came about, which took place following the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC): “We noticed that the favela needed much more than just an improvement in water and sewage supply or better circulation around the territory. We started to think about our memory; we wanted the favela to be recognized and we understood that what attracted people to PPG [as the group of favelas is known] was tourism. How were we going to make tourism bring public investments to the favela? Then came the great insight, social museology, which introduces the ecomuseum. The museum is not what is inside, but what is around us, what is outside, what is inside, so that the whole favela became a museum… The collection being the people, which is what organizes memory. Everyone can and should create their own museum in their territory. Every place must have its museum because memory, over time, speaks. We are city, we are heritage, and memories cannot be removed.”

Souza ended her participation by recalling the terrible atmosphere that reigns in a community threatened with evictions. She described how it affected the residents of the favelas in the complex where she lives. “We also had forced evictions in Cantagalo, many people lost their homes. I was born and raised in Cantagalo and I had people close to me die of sadness because they saw their homes, their castles be torn to the ground. So, that was one of the reasons I got involved in the Favela Museum. To this day, we miss people who left unhappy. Even today, when people hear about some kind of government intervention, the first thing that crosses their minds is: am I going to be evicted, am I going to lose my castle?”

Group Activities Created Proposals to Be Forwarded to the National Popular Conference on the Right to the City

The second part of the meeting was reserved for a group activity in which randomly selected problems were to be addressed through discussion and short, medium or long term proposals. The objective was to have these proposals forwarded to the national meeting of the Popular Conference on the Right to the City, which took place in early June, in São Paulo. Other results were: to build closer ties between activists; to improve collective and direct deliberative mechanisms; to stimulate the organizing of territories in the struggle for permanence; and to realize community proposals when dealing with governments.

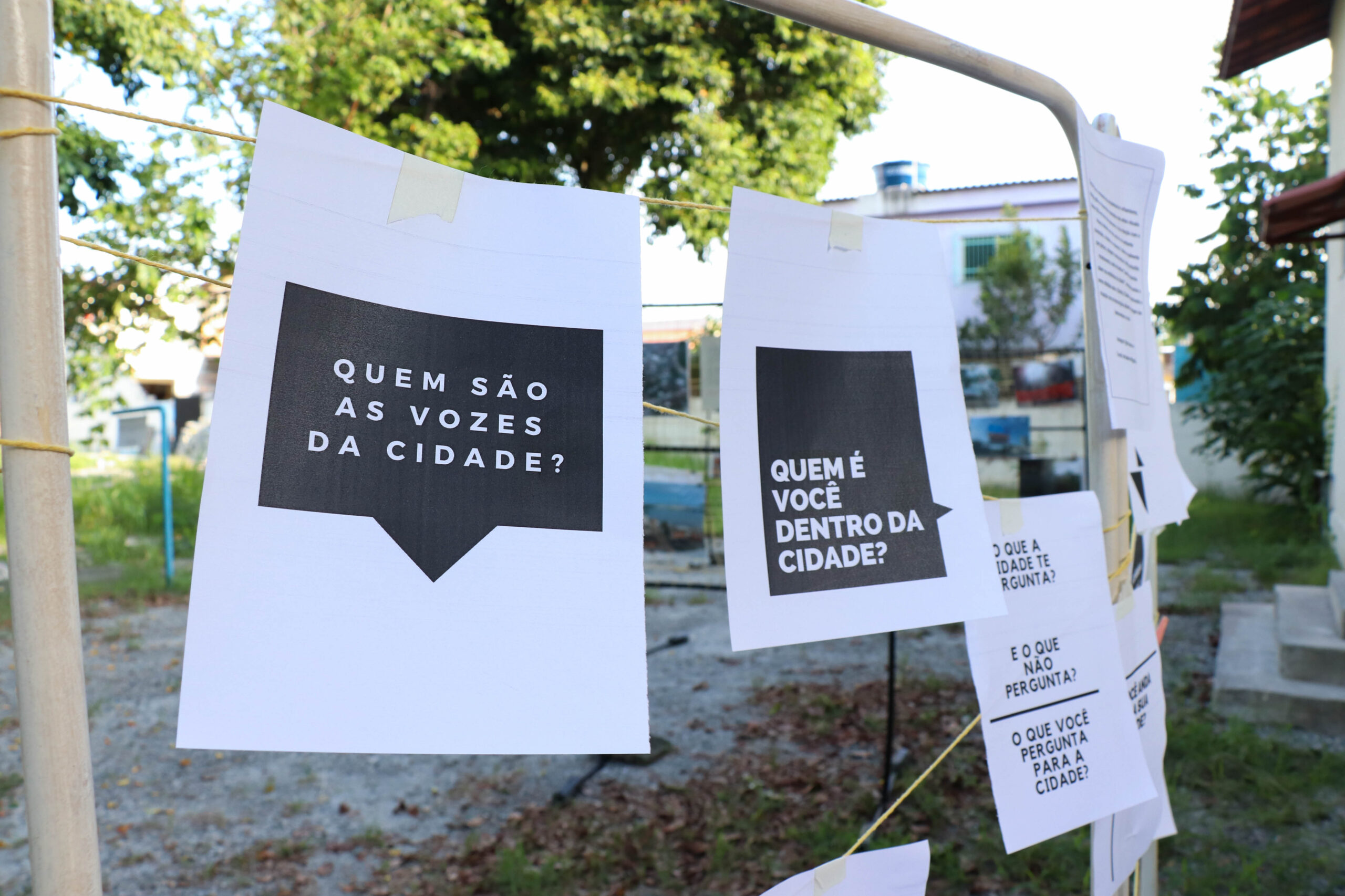

Two groups were formed, both responding to the following questions:

- Having memory as an instrument of struggle for dignified housing and the right to the city, what legal instruments do you envision to guarantee both social museology and dignified housing as rights? Would it be possible to draft a bill for this purpose?

- How can we finance community museums? How can we learn the training needs of community guides who work both within the community and outside it, building a view of the city from the perspective of communities and favelas?

- How do we create instruments for effective popular participation on the walls of the interventions that happen in the territories; in the drafting, execution and inspection of these actions based on self-management, local culture and knowledge of the territory by the residents, and stimulating income generation?

- Collective action and self-management are transformative practices in the struggle for housing and permanence in the territory. How can we complement these actions? Do you know instruments that work towards this end?

The result of this activity was presented to the group with the use of posters and speeches. The first group shared the following considerations, represented by Sandra Maria de Souza, a resident of Vila Autódromo and member of the Evictions Museum:

“Many favelas are already able to see social museology as an instrument for preserving memory and for fighting for housing. How crucial the issue of memory is!… The Evictions Museum itself was born from the struggle for housing, which is a struggle of all favelas… That’s everyday life for a favela: the fight to see your right to housing recognized, to occupy and live in those territories. And then we understand how powerful an instrument memory is in this struggle. Because, it is through the preservation of memory that we prevent the erasure of history.

We also reflected on how the need to organize these memories arises in these groups, since traditional museums do not do the job of preserving these memories. So these social groups—from favela residents, quilombolas and indigenous populations—who do not have this preservation done for them and who do not have a voice in these traditional [museum] spaces, organize themselves; they begin to organize their own memories and to realize the power of this memory as an instrument of struggle.

Traditional museums… manage to raise funds every year, huge amounts of money, because they are already institutionalized, they are already registered. But… the format of social museology is very different: we have a whole construction of memory, but when we try to record it… we face a series of barriers because there is already an established format [for traditional museums], in which we cannot fit. So, we need a law that modifies this format, that adapts, that allows the registration, the institutionalization of social museology, but in a different format.

From the moment that we are able to institutionalize these spaces… and can start to compete for public bids and to raise funds like traditional museums do, we will have the financial means to pay our professionals, not just the tour guides but other professionals who participate in this construction and who usually do so as volunteers. Our proposal is that… this law be created through the city’s master plan, so that it recognizes social museology, which is so far ahead in Rio de Janeiro right now.”

During the final round, the second group, represented by Nathalia Macena, a resident of Vila Autódromo and member of the Evictions Museum, introduced a very important discussion on awareness and community engagement in the favelas:

“The resident is a fundamental piece. Why don’t residents show up at meetings, why don’t they participate in the community’s actions? Many don’t go because of the struggle for survival, because of how hard it is for women, for mothers. What can we do in our communities so that residents can participate more in collective actions? How can we find ways, create actions to attract young people in the favelas? Our debate revolved around this: what can we do to attract our people, our neighbors, and the young people who will be our future?

We are here today, and tomorrow there will be others: so what can we do for this movement to be perpetuated? How do we raise awareness? We organize through art, through culture, which is what happened here at the time of the forced evictions. We need to attract young people, we don’t see young people. Social and digital media emerged as strategies, as well. Creating care spaces to sensitize and bring women in, especially on the frontlines of struggle. So, we have to carry out actions in connection with sports and culture.

Change only happens through awareness. If we’re not aware that it’s important to fight for our rights, we will not change, we’ll stay in the same spot forever. Ask a young person if public policies serve them. Do you have garbage collection? Do you have drinking water? When it rains, does it flood?

We need to take these discussions to them so that they feel they belong. They too have a sense of belonging to the place. This is very important: when you feel that you belong to your community, you begin to understand the importance of that space to you. It’s about seeking our ancestry, our roots, our references so that, having this awareness, we see ourselves recognized, represented… We need to know our origin, where we come from, so that we can fight for our rights.”