On May 3, the Pólis Institute organized the event “Dialogues about the Right to the City and Energy Justice. ” The activity was a preparatory meeting for the Popular Conference on the Right to the City, which took place at the beginning of June in the city of São Paulo. The webinar’s goal was to share the experiences of civil society organizations and social movements in their fight for energy and climate justice and for the right to the city, contributing to the access to energy as a social right.

The event’s mediator, Ana Sanchez, invited activists and technical experts to the debate. Presentations were made by Gisele Moura, environmental scientist and co-coordinator of Rio de Janeiro’s Sustainable Favela Network*; Carolina Marçal dos Santos, activist and environmental manager at Climainfo; Marcelo Cavanha, coordinator of the Central Única das Favelas (CUFA) in Jardim Ibirapuera; Gabriel Mantelli, lawyer and advisor at Conectas Human Rights; and Clauber Leite, environmental engineer and coordinator for energy justice projects at the Pólis Institute.

Moura was the first to introduce herself, describing the production of a series of articles about energy justice for RioOnWatch in 2021, which included 18 productions addressing environmental racism, energy exclusion, the importance of social tariffs, and various solutions arising from peripheral territories, through reports, research and analyses, mostly produced by favela residents.

“This series represented 23 territories, between the favelas, quilombos, and peripheries of Rio, and provided a space for dialogue that extended itself from the local to the global,” said Moura.

Electricity, a Luxury Item

Carolina Marçal dos Santos was next to speak representing the organization Climainfo. Santos was previously responsible for mobilization of the Zero Deforestation campaign, which delivered a bill to the National Congress in 2015 signed by over 1 million people.

Santos broke down the current reality of energy access in Brazil:

“Electricity and gas take up more than half of the income of 46% of Brazilians. This was a study conducted last year by Ipec Inteligência. And when we look at the energy bill alone, we see that 22% of Brazilians are not consuming some food staple in order to pay the electric bill. So, energy has practically become a luxury item in Brazil.”

To Marcelo Cavanha, coordinator of CUFA Jardim Ibirapuera in the city of São Paulo, democracy has never materialized in the periphery. According to him, the pandemic worsened historically difficult situations in favelas. “Before the pandemic, CUFA never did the things we’ve done in the past two years, like this process of distributing baskets of basic foodstuffs, and other items.” Cavanha also believes that the right to the city is something that needs to be demanded from current political candidates since we are in an election period.

Race, Climate, and Energy

There is no thinking about energy justice without considering the agendas of racial and climate justice. We need an agenda that explicitly confronts climate and environmental racism. Lawyer Gabriel Mantelli, a member of the organization Conectas discussed this approach. To Mantelli, thinking about access to energy is understanding who consumes the most energy and who lacks access to it. Generally, this is divided by race and social group.

Mantelli criticized the government’s stance, which has recently been adopting energy policies that violate climate agreements, prioritizing production models that are harmful to the environment. “If on the one hand, community initiatives have done vital and necessary work advancing the discussion on how to guarantee local access to energy, on the other hand, as much as Brazil has considered itself a great exponent of clean energy production, recently the federal government has not acted in the way we’d hoped it would,” said Mantelli.

The activist also pointed out that the current government has invested in carbon-intensive projects, that is, projects that ignore the impact caused by climate change. This violates human rights and disregards the people who will be most affected by extreme events resulting from climate change.

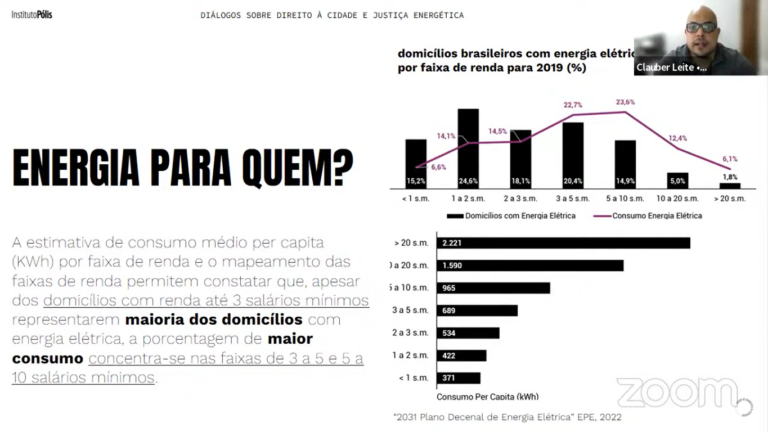

The roundtable discussion finished with environmental engineer Clauber Leite, who coordinates the Pólis Institute’s energy justice project. Leite opened with a thought-provoking question: “Energy for whom?” He said that the lower the person’s income, the lower their energy consumption. “People who earn more than 20 minimum monthly wages consume ~2,200 kilowatts per hour, while those who earn between one to two minimum monthly wages tend not to exceed 500 kilowatts per hour,” said Leite.

Leite pointed out that climate change is more present in our day-to-day lives than we imagine mainly because of the poor choices that public authorities have made regarding energy. “These wrong choices include the use of thermoelectric plants, nuclear energy and incinerators. We’ve been watching this increased pressure for the use of energy that is much more expensive and polluting invade our grid.”

The conversation between the participants showed that a basic good like electricity is turning into an increasingly valuable commodity that is difficult for low-income populations to access. Energy policy decisions are made by bureaucrats who have never had to choose between paying for electricity or buying food. However, there is a path forward, and that involves strengthening local initiatives and investing in clean and sustainable energy.

Watch the Event “Dialogue on the Right to the City and Energy Justice” Here:

*The Sustainable Favela Network and RioOnWatch are both projects of Catalytic Communities (CatComm).

About the author: Euro Mascarenhas Filho is a journalist and contributor to the Piratininga Communication Center (NPC) news service. He is author of the podcast Antena Aberta.