This is our latest article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on climate impacts and affirmative action in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

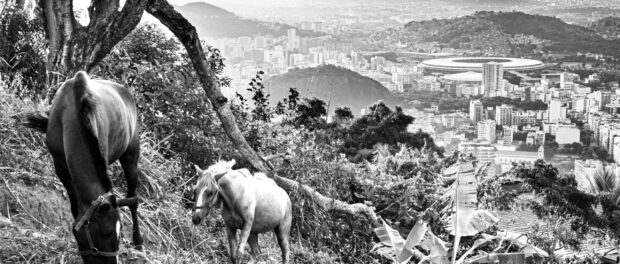

Across the world, discussions about climate change and the urgency of caring for the environment in order to halt, or at the very least, reduce its impacts have been going on for some time. However, with the continuing increase in deforestation in Brazil—not only in the Amazon but also in the Atlantic Forest and the Pantanal—managing the impacts of climate change in urban and rural areas is also increasingly difficult. Extreme weather events are occurring more frequently throughout the country.

Favela residents with homes on hilltops, on slopes, or beside rivers are increasingly experiencing the effects of climate change. Heavy rains that fall at certain times of year flood houses and streets close to rivers and ditches. Landslides destroy hillside homes. Deaths from these events are sadly common.

These phenomena leave some displaced and homeless, forced to live in public shelters or with relatives. Local governments in Brazil generally register them for social rent if they are unable to access public housing programs such as Minha Casa Minha Vida. But not everyone affected is covered by these programs. And even when they are, many report the payments received are lower than rents charged in favelas.

Thus, many favela residents choose to return to their former addresses to rebuild their homes. Others join the homeless movement, occupying vacant lots or abandoned public and private buildings that are not fulfilling the “social function of property” as outlined in the Brazilian Constitution.

To learn more about how climate change impacts the lives of residents, I visited the Turano favela, located between the neighborhoods of Rio Comprido and Tijuca, in Rio’s North Zone. I started in a particular area, known as Pedacinho do Céu, or “little piece of heaven,” in the upper part of the favela which is especially vulnerable to rains. There, I spoke to residents who directed me to a neighboring area where landslides, mudslides, and flooding due to garbage is also common: the “Tanque.” It’s important to note that Turano is a very large favela with several other areas high up on the hillside, such as Bicão, Esperança, and Caixa D’Água. However, the two neighborhoods this article focuses on are at the very top of the hill, with lots of ravines and narrow alleys which aren’t even accessible to motorbikes.

At the entrance of Turano are well-built brick homes with electricity, running water and narrow paved streets. Slopes are lined with trees and there are concrete walls to prevent landslides on rainy days. Streetlights are in good condition.

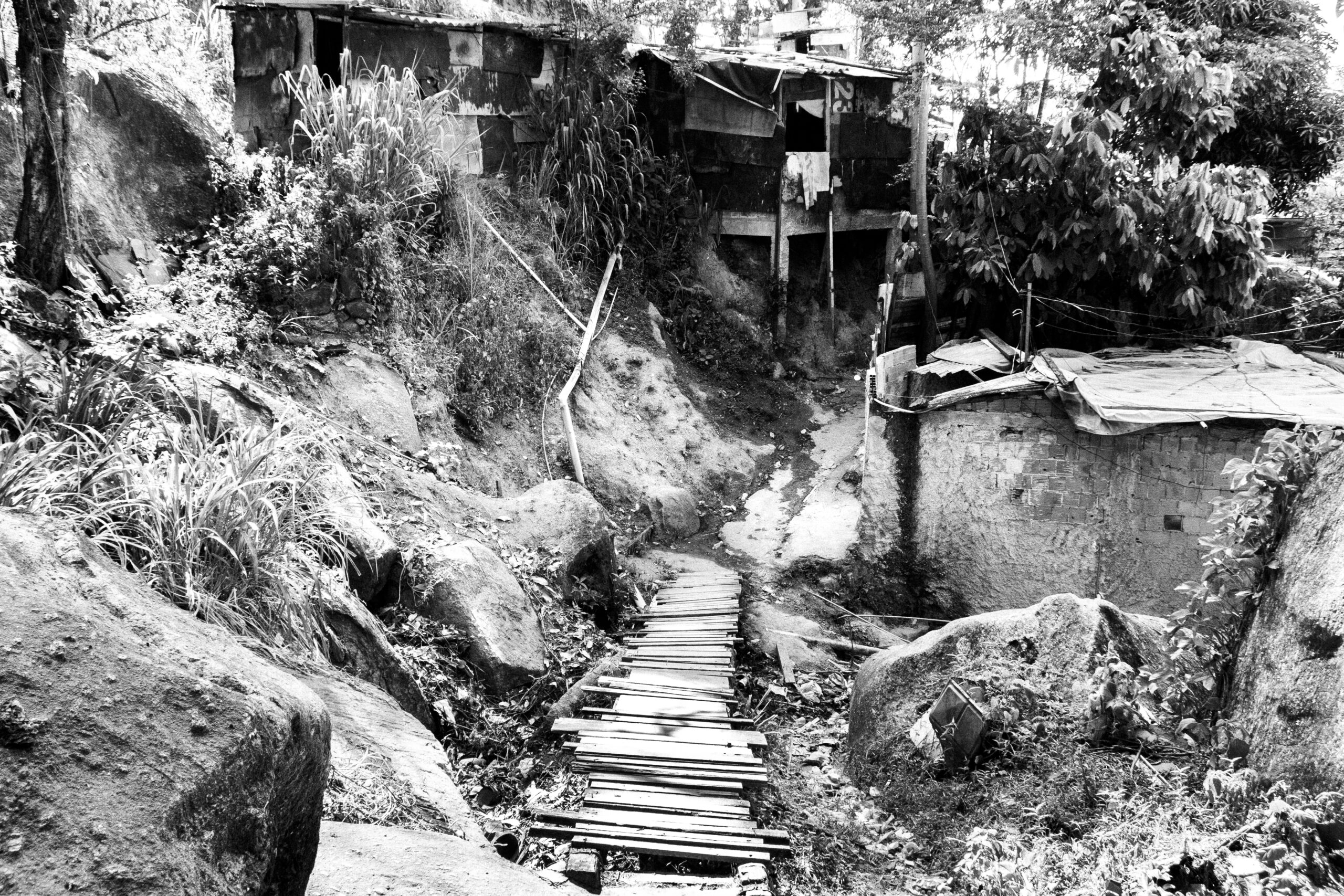

However, once we reach the top part of the favela, the public infrastructure is completely different from down below. In these elevated areas, many shacks are built directly onto slopes. Some are very precarious, others are well-built and made of brick. There are a number of more improvised mud and wood homes.

A few years ago, when I was working on another project in the area, I saw a house built entirely out of the material used for office cubicles among these homes. It was located very high up on the hill, in a ravine. It had a single lightbulb, much like other homes in the area—a recurring scenario in the tops of Rio’s favelas.

Upon returning to the neighborhood this year, I found that the cubicle home was no longer there. Many other homes I’d seen in 2019 no longer exist. In their place today are piles of rubble, garbage, loose piping, and a thicket of vegetation that covers a large part of the path that still passes through that part of Turano. Lamp posts stand in precarious conditions along the way: corroded, slanted, and in some cases supported entirely by wiring. If these wires break, the lamp posts would collapse. The highest part of the hill, previously home to a lot of people, now only has a few residents who endure this state of affairs as best they can.

The complete absence of public services in this part of the favela is alarming. Ravines are giving way, gradually eroding with each bout of rain. With a few more storms, which are common in Rio, it’s likely these will collapse, wiping away everything and everyone in their way. Tall trees grow on unstable soil and without proper care from the authorities. They are also a cause of concern among residents: they’re close to falling onto their houses. It’s a tragedy waiting to happen.

One of the houses I visited in 2019 used to be occupied by a woman and her pregnant daughter. Back then, it was already in precarious condition and did not have electricity. The woman and her daughter cooked outside in their backyard, on a makeshift brick stove, using charcoal and a refrigerator grill. When I spoke to the pregnant daughter in 2019, she said she felt no danger living there: she was already used to it, and while almost everything got wet when it rained, she could sleep wherever the water hadn’t fallen. Today, the house is even more rundown.

Today, João,* the current occupant, also says he sees no danger in living there. He says he’s not worried about the possible collapse of the slope it’s built on. “When it rains a lot, everything gets wet. My yard gets flooded, my house. So I go somewhere else until the rain stops and then come back home,” he explained. While spreading a quilt he’d just washed on a wooden fence, he went on: “I’m not scared. Here… no one bothers me and I don’t bother anyone. I don’t have anywhere else to go, so I stay here, in peace. This is my home.”

As we talk, marmosets run back and forth between trees and electric wiring. João interrupts himself to speak to the animals and warns me they might jump or pee on me: they’re calm animals but they’re not used to me. I move away from them and approach the front of the house. I see the remains of the makeshift stove where the former resident, pregnant at the time, cooked in 2019.

I ask to take a few photos and João says it’s good to report on the reality of the place. He says: “I’m happy here, and I haven’t thought about leaving at all. This is the best place to live—it’s peaceful. I work making my deliveries [a service loading and delivering groceries and construction material for other residents who live in the upper part of the favela] and collect PET bottles because I also work in recycling. Then there are the little animals to keep me company. And when it rains, I just do my best to deal with it.”

I say goodbye to João and walk a little further into the upper part of Turano. Along the way, I meet Elisabete,* who lives in a well-built brick home in an area where the hillside is protected by a retaining wall. I ask her the same question that I asked João, to which she answers: “I don’t have any problems with the rain here. It’s safe down here. If you go higher up, yes, it gets dangerous. After the heavy rains and landslides in 2010, many people from up there left. A friend of mine who lived there moved to Minas Gerais. Her house was destroyed.”

Elisabete adds that, after 2010, there were no more reports of landslides in that part of Morro do Turano. According to her, the city evicted a lot of residents and resettled them in other places.

I walk a little further down towards an alley just below Elisabete’s house. There I find Geraldo,* another resident of Pedacinho do Céu. He’s standing in front of his house when I ask him about the impact of the rains on this part of the favela. “It’s fine over here. We haven’t heard any more news of landslides or collapsed homes after 2010. As far as I know, at least. Now, if you go further up, things get crazy; it’s really dangerous up there. Up there, when the water comes down, it brings everything with it. Still, I haven’t heard anything else about houses collapsing, only mudslides.”

Geraldo says he was raised in Pedacinho do Céu and that the large landslide in the area in 2010 meant the city evicted residents, moving them to other neighborhoods such as Triagem, Manguinhos, Bangu, and Campo Grande, through the Minha Casa Minha Vida program. Geraldo’s mother was one of the people affected: she left her home in the upper part of Turano and settled in Campo Grande, in the West Zone of Rio, in an apartment built by the government. “My mom didn’t live in a high-risk area, but the city thought it would be best to get everyone out of there. She and everyone else accepted the compensation they offered and settled in other places. I didn’t want to, I preferred to stay here. Water doesn’t get into my house, and this alley here is peaceful. It’s very safe here.”

Geraldo is remodeling his house: he says that if he had the means, he would leave the favela but only if he could move to a neighborhood with better infrastructure. At the end of our conversation, he recommends that I visit another neighborhood in the upper part of the community called Tanque. According to him, the impact of the rains there is much greater. According to him, it’s a “real area of risk,” when it rains heavily, lots of mud and garbage come down the hill.

Following Geraldo’s advice, I go to this part of the favela. Before getting to Tanque, while still in Pedacinho do Céu, I meet Creuza* who lives in a brick home with her children. The house isn’t plastered on the outside and there are cracks in the walls. A large ravine sits just behind the plot of land, filled with rocks, slanted trees, and a lot of trash. I ask her what she does during the heavy rains.

“Nothing’s happened while I’ve lived here, but it’s very dangerous. It got a bit better after they took down a few of the trees that were about to collapse, but still. When it rains hard, I go to my mother’s house, or to my mother-in-law’s. I immediately look for a place to stay with my kids. I’ll tell you this: it’s not easy living here. Especially in this house. Even when it’s just drizzling, everything gets wet,” says Creuza.

“Nothing’s happened while I’ve lived here, but it’s very dangerous. It got a bit better after they took down a few of the trees that were about to collapse, but still. When it rains hard, I go to my mother’s house, or to my mother-in-law’s. I immediately look for a place to stay with my kids. I’ll tell you this: it’s not easy living here. Especially in this house. Even when it’s just drizzling, everything gets wet,” says Creuza.

Creuza’s neighbor interrupts to point out the danger represented by the large boulders that sit on top of upper Turano, which can easily roll down during heavy rains. There are many homes where the boulders would fall, causing material damage and deaths. The neighbor says he lives further down from Creuza and that when it rains water floods his and his neighbors’ houses. However, he reiterates that the rocks are his only concern, as they have the potential to destroy the whole neighborhood.

Creuza says mud slides down when it rains and completely blocks the pathways, making travel impossible. When this happens, residents get together to clear the area. She says that many residents in the higher parts of Turano, such as Pedacinho do Céu or Tanque, have left and abandoned their homes because of the danger of living there. She adds that she would do the same if she could: “I’d go too if I could. But unfortunately, I can’t go yet. So I live here with my children and pray that nothing happens. I have faith that nothing’s going to happen.”

I leave Creuza and continue on to Tanque. On the way, when I’m almost there, I see one of the rocks that frightens residents: a huge boulder propped up by a thin concrete column. Below is a vacant lot filled with trash and surrounded by homes.

I leave Creuza and continue on to Tanque. On the way, when I’m almost there, I see one of the rocks that frightens residents: a huge boulder propped up by a thin concrete column. Below is a vacant lot filled with trash and surrounded by homes.

Just as I arrive, two residents walk past me. I ask if we can talk and they tell me that one of the biggest problems they have on rainy days is the huge amount of garbage that slides down the slopes. They say their homes don’t fill up with water but that the paths get covered in trash and mud. One of them says the Civil Defense and the city evicted some people and claimed they were going to close off the entire area, though that never happened.

Walking through the whole area and talking to residents, the absence of public authorities is glaring. This cruel scenario is clearly caused by government negligence. People don’t live in the upper parts of favelas with precarious services because they want to. It’s striking that most of the residents I spoke to from this area said they have nowhere else to go, and that they would go somewhere better and safer if they could afford to. On rainy days, no matter how much water falls from the sky, everyone wants to take shelter in their own homes—not have to rush out and look for somewhere else to stay because of floods, overflowing garbage, or landslides.

There’s an urgent need for public policy to address the impacts of climate change in the favelas. Otherwise, we’ll have an escalating number of tragedies, with growing numbers of people without homes and millions of lives impacted by state negligence and environmental racism. Unfortunately, so long as there is no climate justice, the lives of Afro-Brazilians and favela residents will continue to be lost.

About the author: Carla Regina Aguiar dos Santos was born and raised in Morro do Turano. Her work as a community journalist has always prioritized the day-to-day happenings in the favelas. Reporting what goes on beyond the view of traditional media, she has contributed to the Favela News Agency (ANF), A Pública, Eu, Rio! and Terra. She received the ANF Award for journalism in the culture category and the Neuza Maria Award for Journalism.

*Pseudonyms have been used to preserve residents’ privacy.