Clique aqui para Português

Poet and writer Sérgio Vaz, founder of the Cultural Cooperative of the Periphery (Cooperifa) and of the Cooperifa Poetry Slam—a movement that turned a bar in the periphery of São Paulo’s South Zone into a cultural center—warns us in a poem titled ‘New Days‘: “Don’t mistake a fight for a struggle: a fight has an end, a struggle lasts a lifetime.”

Vaz’s recommendation serves as a metaphor for our analysis of the 2022 elections in Brazil. For the sixth time in a row, the presidential race will be decided in the second round of voting to take place this Sunday, October 30. In the first round, according to Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court (TSE), former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva (Workers’ Party, PT) came first with 48.43% of the votes and Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party, PL), seeking reelection, had 43.2%. As such the Left’s dream of an all-out win in the first round, as opinion polls had been anticipating, did not come true. But the fact is that Lula beat Bolsonaro in the first round.

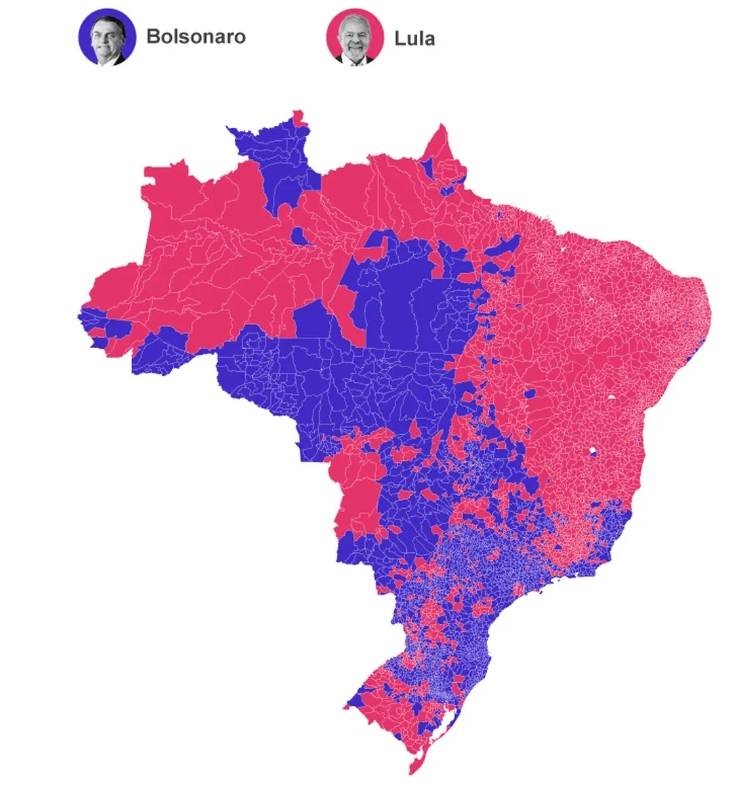

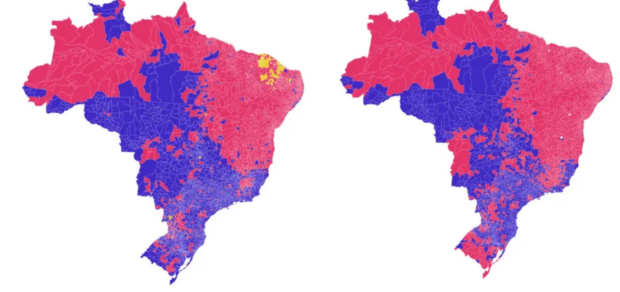

On the one hand, these results were a significant victory for the Left that shouldn’t be underplayed. However Lula’s win in 14 states and Bolsonaro’s in 12 plus Brasília, the federal capital, reveal the consolidation of the polarization of two antagonistic forces: the Left and the far-right.

The competitiveness of the presidential race intensified due to the public’s dissatisfaction with Jair Bolsonaro’s administration. According to the last Intelligence in Research and Strategic Consultancy (IPEC) opinion poll (BR-01120/2022), the incumbent’s rejection rate is at 53% for the second round. In addition to this forbidding rejection rate, there were the annulments of Lula’s convictions in the Operation Car Wash corruption investigation. Supreme Court Justice Edson Fachin ruled that the case against Lula should have been conducted in Brasília, and not in Paraná. This lack of jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Paraná combined with the recognition of former judge Sergio Moro’s partiality in the former president’s conviction led the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) to annul all cases against Lula by seven votes to four.

As pointed out by Judge Ricardo Lewandowski in his vote favoring Habeas Corpus 164493/PR: “The patient [Lula] did not receive a fair and just trial according to the canons of due process but, rather, was submitted to a veritable mockery of a criminal proceeding whose nullity is plain to see and necessitates no further legal consideration.”

Having become Bolsonaro’s Minister of Justice shortly after illegally sentencing Lula to prison, former judge Sérgio Moro was elected to the Federal Senate for the State of Paraná with 1,953,159 votes (33.5% of valid votes). Forty-eight hours after the first round, he declared his support to Bolsonaro for the runoff.

Bolsonaro is the first president in Brazilian history to lose the first round while attempting reelection. Lula was exactly 6,187,159 votes ahead of Bolsonaro. However, Brazil has also never had a president run for reelection who did not win. Therefore, the second round for Brazil’s presidential election promises to be cutthroat, taking the struggle between Left and far-right politics to a peak.

But What Does That Mean?

In practice, it means the phenomena of Lulism, anti-PT agendas, Bolsonarism, and anti-Bolsonarism all fighting over national projects that are completely antagonistic. That is the analysis of Mayra Goulart, professor of political science at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and coordinator of the Laboratory for Political Parties, Elections and Comparative Politics (LAPPCOM).

She highlights that second round races tend to favor far-right candidates:

“Far-right populism is favored because it follows a Manichaean idea of dualism. It starts off by simplifying the understanding of oppositions: friend and enemy, good or evil. And the second round favors this polarity because it is the simplification of the political sphere into two options.

Another aspect that favors a far-right candidate in the runoff is the fact that they already have a certain ease with demonizing their adversary, using fake news and cognitive dissonance bubbles—which are those information bubbles on WhatsApp [and Telegram], that favor far-right candidates in this final stretch… There’s a barrage of fake news.”

However, ever since the possibility of reelection was approved in the country, the second-place candidate in the first round has never been able to revert the situation in fighting for the presidency. Even so, Goulart notes: “We have a hard-hitting candidate who has used the government machine like never before in the country’s recent history, injecting R$40 million (US$8 million) into society with discontinued, electioneering public policies that have a definite end date.”

Goulart also believes we must take into account that, in the clash between the anti-PT agenda and Bolsonarism, we have a candidate, Lula, who experienced a serious smear campaign and has, nonetheless, remained on course in several channels. For this reason, she believes that having a candidate like Lula receive such an expressive vote in the first round is an important achievement.

“Particularly a Lula that did not lean to the Right, that came forward as the candidate of inclusion and social mobility with a leftist economic agenda; he did not write a new governance proposal to present to the Brazilian people but, rather, maintained his previous commitments. Those who voted for Lula voted for a leftist candidate.”

According to Goulart, if the anti-PT agenda structured the entire Brazilian political system in the last elections, in 2022 we have the collision of two phenomena: the anti-PT agenda and anti-Bolsonarism. Together, the two are reorganizing Brazil’s entire political system.

The proof becomes visible when we look at the first round results in detail. Although Lula got 57,259,504 of the valid votes, on October 3 Brazil woke up more pro-Bolsonaro than ever before. President Jair Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party grew and will have the biggest bench in the Federal Chamber of Deputies in 2023, having jumped from its 76 current deputies to 99. The country that placed its votes at the ballot boxes this time around elected a more Bolsonarist Congress than in the 2018 elections.

An example is former Minister of the Environment Ricardo Salles (Liberty Party, PL-SP) who resigned from the Bolsonaro government after strong evidence that he had been favoring illegal logging. Salles received the fourth highest number of votes for a federal deputy in São Paulo—640,000 votes.

Another beneficiary of this pro-Bolsonaro surge in Congress is retired general Eduardo Pazuello (Liberty Party, PL-RJ). One of the health ministers in Bolsonaro’s government, his management of the Covid-19 pandemic was chaotic. As established by the Covid-19 Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI), Pazuello was directly responsible for the State of Amazonas running out of oxygen, which resulted in the death of thousands. Even with such a background, Pazuello received the second highest number of votes for federal deputy in Rio with 205,324 votes.

Support for him in Congress means that if Jair Bolsonaro is elected in the second round, he will have the power to change the Constitution and alter the structure of the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) by approving the impeachment of its judges through the Senate. His party, PL, now has 14 of the 41 seats.

Among the senators elected, four are his former ministers: Damares Alves (Republicans), Marcos Pontes (PL), Tereza Cristina (Progressive Party, PP) and Rogério Marinho (Liberal Party, PL), in addition to current vice president Hamilton Mourão (Republicans).

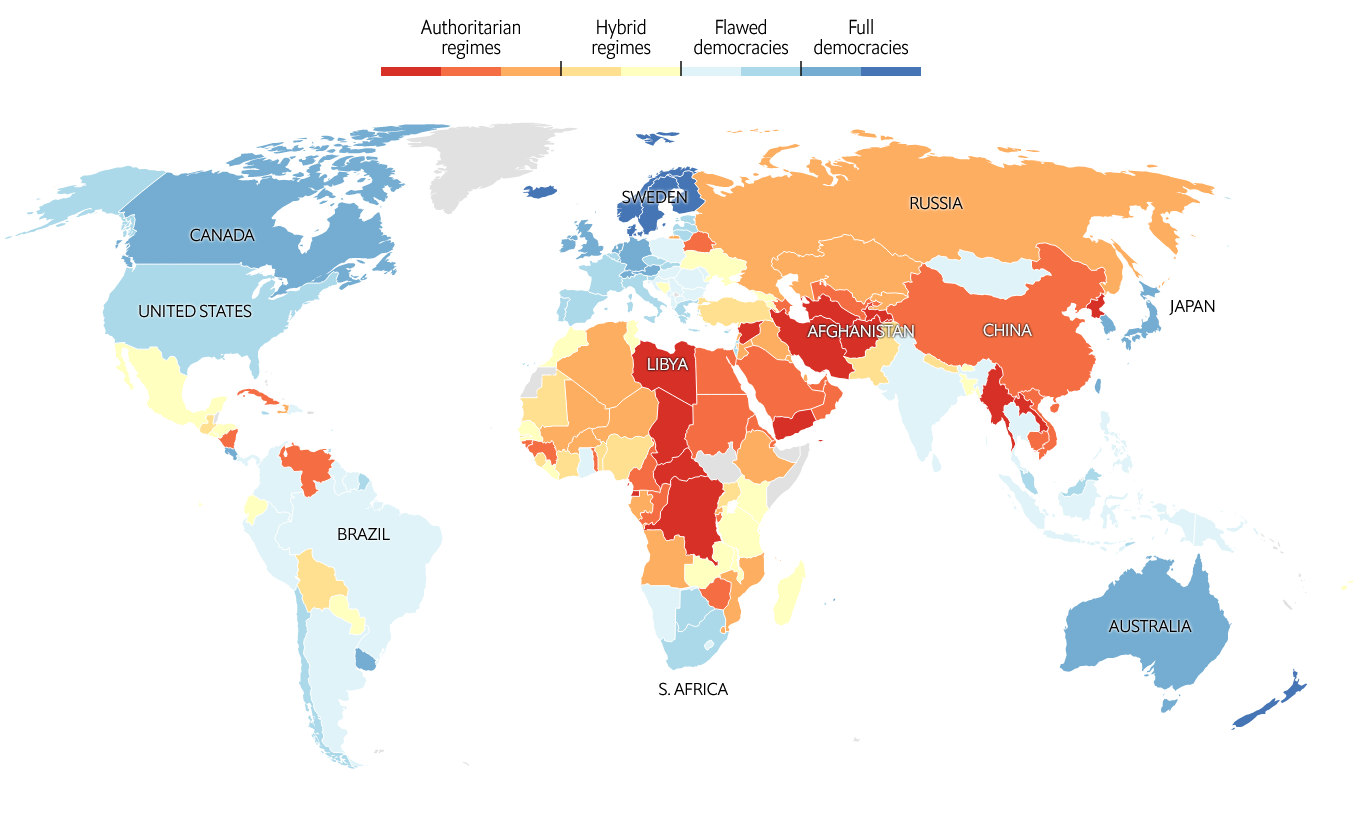

It is undeniable that the path is open for the possibility of establishing an authoritarian regime in the country. The far-right has gained power and now vies for Brazilian society’s values. With the way paved for the establishment of an authoritarian regime in the country, democracy is at risk. According to Goulart:

“We have a population that is not entirely pro-Bolsonaro. The 43% [who voted for him] are not all with Bolsonaro. Many voted for Bolsonaro due to an anti-PT agenda. But yes, within these figures we do have the radical Bolsonarist, a segment of the population that is more conservative and wants the return of the patriarchal society [the military regime] of the past with undisputed patriarchal authorities… This is indeed a danger for democracy since [among these voters] there is no appreciation for democratic values.”

The Political Context

A poll published by Datafolha shows that support for democracy is currently at a record high in a country where, only a year ago, 45% believed their country might become a dictatorship.

The TSE regulated Electoral Observation Missions (MOE) to monitor the elections through Resolution no. 23,678/2021. Brazilian civil society organizations and social movements have also invited human rights defenders to observe the nation’s elections fearing an institutional rupture in the country.

The fear of a coup is owed in part to the increase in political violence in the country and to the speeches given by President Jair Bolsonaro. In addition to several statements in which he has attacked Brazilian Supreme Court justices, Bolsonaro discredits the Brazilian electoral system and raises baseless doubts regarding the electronic voting system, which is verifiably secure.

Nine Supreme Court justices followed the first round vote count within the TSE. Even if a coup is improbable, Brazil’s democracy was classified as “flawed” by the Global Democracy Index, which is based on a few variables considered crucial for good democratic development.

According to The Economist, Brazil is currently viewed internationally as a “failed democracy” with “limited capacity to offer solutions to its citizens’ demands within traditional political institutions and the possibility of exercising one’s political rights in a context of peace, freedom and fair play.”

As such it is crucial, considering the country’s current political scenario, “to not mistake a fight for a struggle” as Sérgio Vaz warns us in his poem. ‘New Days’ will only be possible through much struggle and the defense of our democracy.

About the author: Tatiana Lima is a journalist and popular communicator at heart. A black feminist, member of Complexo do Alemão’s Researchers in Movement Study Group, she is currently special reporter with RioOnWatch. A fair-skinned black woman, born and raised in a favela, Lima currently lives in Rio’s periphery and is a doctoral student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF).