This is our latest article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on water issues and the LGBTQIAPN+ population in Rio’s favelas and in the Baixada Fluminense for RioOnWatch.

The Global Climate Strike is an annual international mobilization which aims to warn about climate change and its impacts on the most vulnerable populations. On March 3, Rio de Janeiro’s participation in the global event—titled Global Climate Strike: No More Floods!—took place in the form of a march from Jacarezinho to Manguinhos, both favelas in Rio’s North Zone. The Rio event had the goal of highlighting environmental racism towards the city’s favelas, which routinely suffer with flooding and landslides.

The decision to conduct the event in Jacarezinho and Manguinhos was made during a meeting led by the Rio de Janeiro Climate Coalition together with the Forum for Climate Change and Socio Environmental Justice (FMCJS), Fase, Brazilian Center for Health Studies (Cebes), Fiocruz Workers’ Union (Asfoc), Sustainable Favela Network (SFN),* and the People’s Watchdog Network for Sanitation and Health.

Beyond these organizations, around 70 people attended the event. Residents, community leaders, and organized favela movements took part, including the Favela People’s Movement, Favelas Portal, Favelação Movement, Manguinhos Community Council, Manguinhos Intersectoral Management Council (CGI), Women of Attitude Organization (OMA), Samora Machel Residents’ Association, Nelson Mandela Residents’ Association, Parque Carlos Chagas Residents’ Association, and Nova Embratel Residents’ Association. Political representatives also attended including City Councillor Monica Cunha, advisors to City Councillor Thais Ferreira, State Deputy Marina do MST, and federal deputies Tarcísio Motta and Henrique Vieira.

The event was a march from the Unidos do Jacarezinho samba school to Manguinhos train station. Demonstrators passed through some of the areas most affected by flooding caused by rains since the start of the year. The first week of February brought more rain than was expected for the whole month, causing devastation and tragedies which particularly affected those living in favela territories—the areas most exposed to the devastating effects of government neglect in the face of climate change.

The Manifesto to Communities and the Rio de Janeiro City Government was handed to residents during the event. The aim of the document is to call attention to the seriousness of global climate change and its consequences for the favelas. It also aims to influence policy and demand an effective commitment from the City to implement initiatives for adaptation and protection of life and which confront environmental racism in the favelas. As the letter states: those most affected by climate disasters in the city of Rio de Janeiro have an address and a color. Organizers will deliver the letter to the City and seek a public hearing with the Rio de Janeiro City Climate and Environment Secretariat, currently led by Tainá de Paula.

Afro-Brazilians and Favela Residents Are Those Most Affected by Climate Disasters

While demonstrators initially gathered at the Jacarezinho samba school, Rumba Gabriel, a local leader from the Favelas People’s Movement, declared:

“I’m here today together with this incredibly interesting mobilization. I’d say it’s the first of a sequence; we’re going to persist because we’re tired of this history of recurring problems. We’ve suffered [flooding] for a long time. To give you an idea, the last large public works on the river that runs through Jacarezinho were in the 1980s… So, these tragedies repeat themselves. We know the rainy season will come and something bad will happen… I think it’s time to put a stop to this and it seems to me that we’re making it all show through the event today. We want structural works, not basic works… This is why I think our cry [today] is going to be important. What we have here is a disintegrated city [criticizing the State government’s Integrated City program] which doesn’t look our way… It’s been a year [since the start of the program] and everything’s just how it’s always been.”

Still at the samba school headquarters, speeches were made by residents affected by floods, community leaders, organizational representatives, and parliamentarians who accompanied the event.

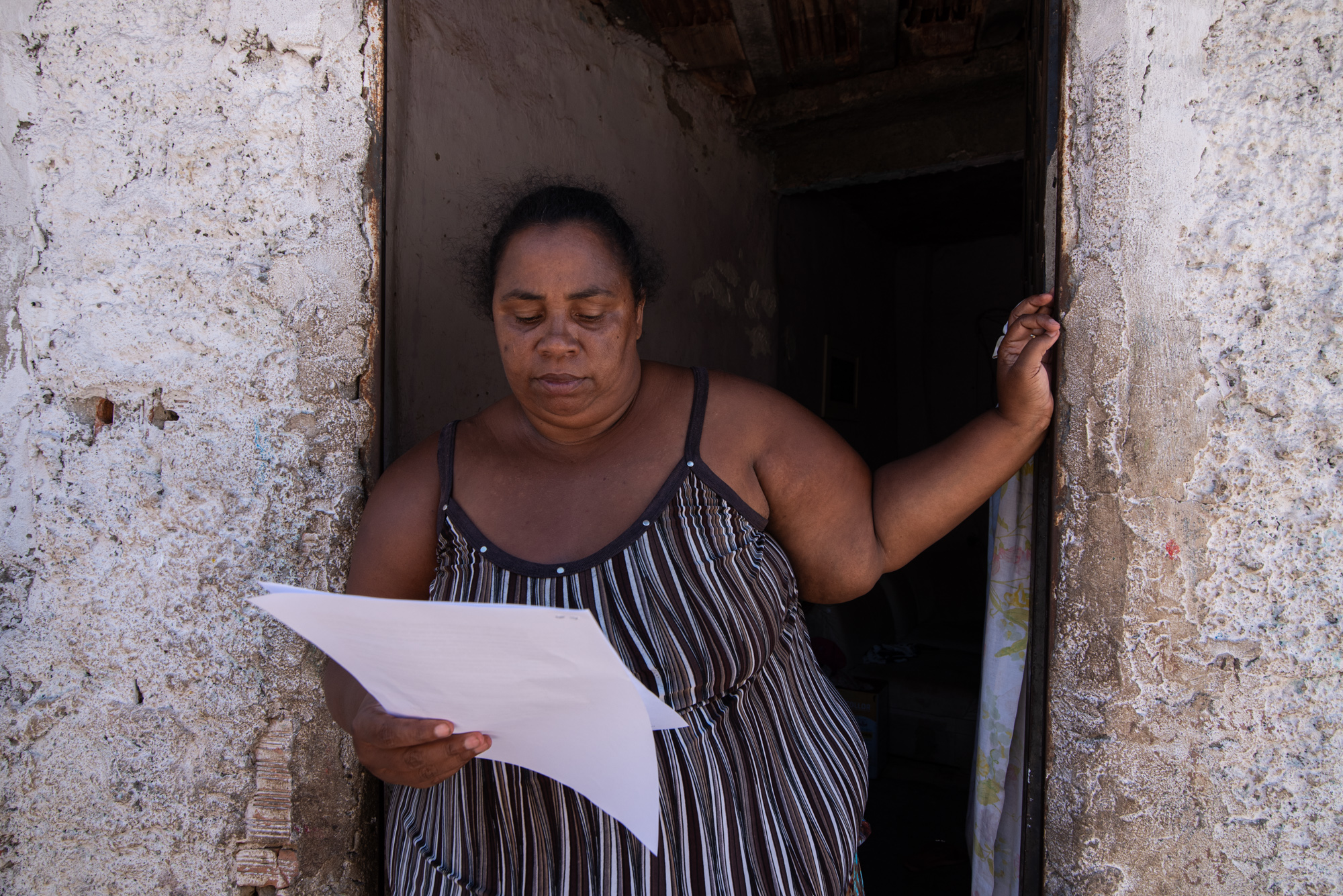

The march began at 10am and passed through the streets of Jacarezinho. During the event, demonstrators delivered the manifesto and shouted slogans. It was clear that residents identified with the demands made. Some took the letter and said “Yes, that’s it!” Others chanted along with protesters. Arriving at the Jacarezinho River, a resident told those present about the annual pattern of flooding in the area.

“I’m Carmem Camerino, I live by the train tracks right there close to the station and what happens here is always the same. Every year there are the well-known summer rains and the river overflows to the point of water levels reaching up to 1.5m inside people’s homes. Unfortunately, since I live by the railway line, I get trapped [at home] every time the river overflows. I have an upper part of the house so I stay up there with my dogs. When the water level goes down, we see the disaster of people who’ve lost their furniture, people cleaning and removing layers of mud from inside their homes. During the latest flood in February, before Carnival, I saw people from the houses lower down swimming in the water to escape the floods. This happens every year. We’ve reported it, filmed it, and now with social media and technology we’ve posted online. But it’s like no one hears, no one sees, or no one cares.” — Carmem Camerino

When the march reached Largo da Concórdia in Jacarezinho, event organizers received reports from residents about a house that had sunk and been closed off by the Civil Defense. Meanwhile the other houses next to the condemned property weren’t even inspected. A team led by representatives from national health foundation Fiocruz and parliamentarians went to the location to check out the situation and confirmed that the house had completely buckled and was being held up by wooden beams improvised by residents.

After this inspection the Global Climate Strike participants went on towards the neighboring favela of Manguinhos, crossing the train tracks and walking along the Faria-Timbó River where there’s an Integrated City program base and dredging machines parked by the river. Residents affirm that these machines “don’t do anything,” just staying parked.

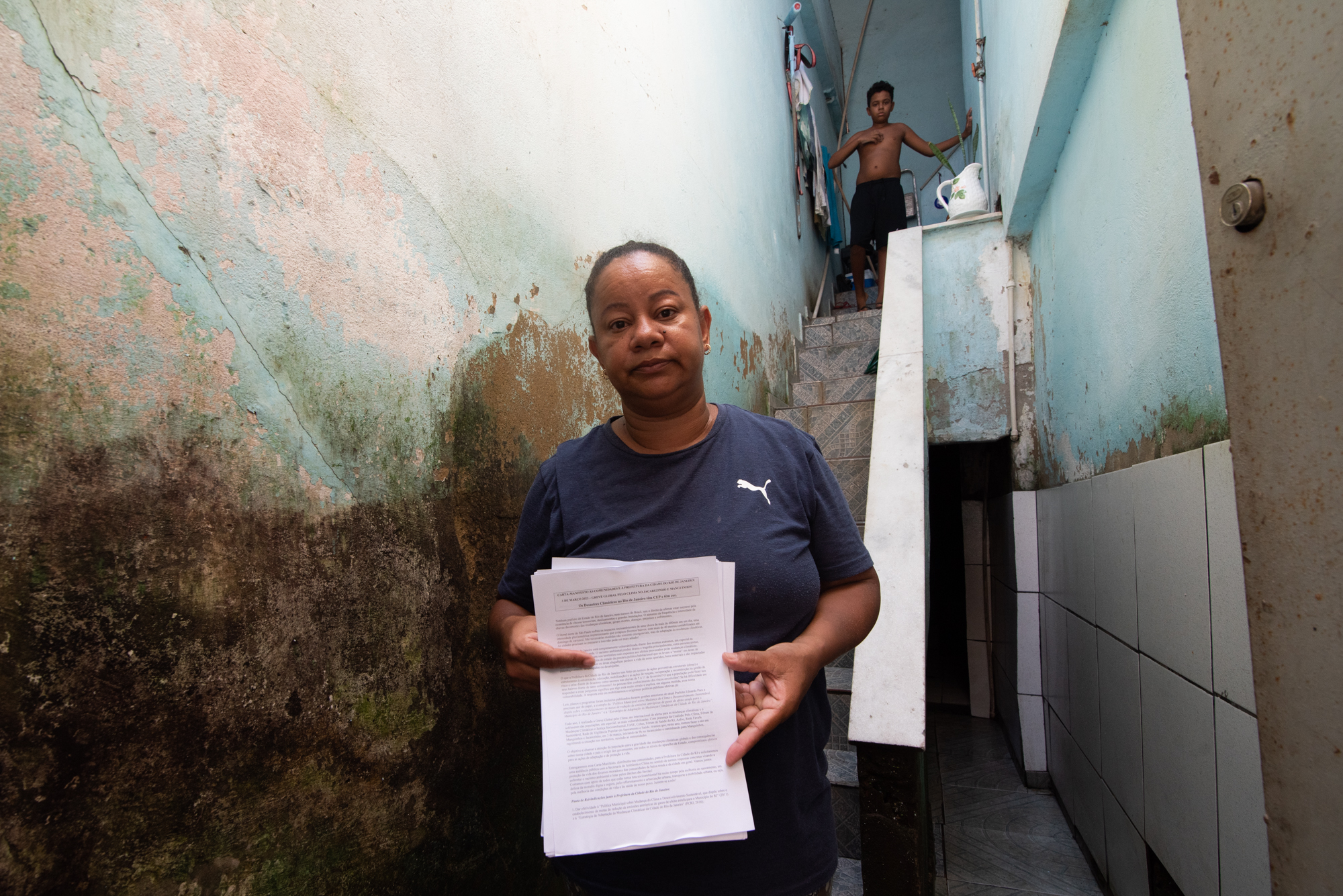

Arriving in Manguinhos, numerous residents shared reports of the losses, climate impacts, and State abandonment in their lives. One of the most striking speeches was made by Maria Aparecida, who said that in the month of February she spent more days away from her home than in it as she believed her life was at risk if she stayed home because of cracks in the walls.

“We live in fear. Sometimes I have to stay under the viaduct with my son waiting to be able to go inside the house. I have to stay with other people. If it weren’t for my best friend, I don’t know what would become of me! My friend lives in Mandela. We’re always running over there! In February we stayed more at hers than mine. My neighbor’s house below mine floods. Her house is condemned. They condemned hers but not mine? My house is all cracked! I live there with my son. Sometimes when he doesn’t have school the neighbor watches him. I’ve already told him, if you need to run, run… that’s if there’s time to run.” — Maria Aparecida

There are many abandoned houses and flood marks on the walls in the area where Maria Aparecida lives. Some of these properties still have furniture ruined by the waters that have been abandoned by former residents who escaped during February’s climate emergency.

We spoke with another resident, Maria Emília, who has lived in Manguinhos for many years. She reported that where she lived, on Rua São José, became inaccessible during the latest intense rains in February, as has happened on many other occasions.

“No one could pass through because there were two meters of water. It’s high here, it doesn’t flood because there’s a stairway, but this part down here floods. People get out by swimming or being carried. Sometimes some good angels show up to help.” — Maria Emília

The Global Climate Strike event ended at the Manguinhos train station where community leaders and event organizers spoke. From the reports of despair and sadness to the destroyed houses and completely clogged up and polluted rivers, it was clear to everyone present that the fight against climate change in Rio de Janeiro will only be effective if it’s guided by and based in the favelas, for the favelas, by the favelas, and combined with intensive public investment in these territories. In the city of Rio de Janeiro alone, there are millions of people who are climatically vulnerable, whose lives are at risk, who see their belongings and the fruits of their labor—sometimes over an entire lifetime—destroyed in a matter of minutes. Environmental anti-racism grounded in the favelas is urgent for the fulfillment of the right to the favela and to guarantee the right to the city in the midst of the climate emergency.

About the author: Bárbara Dias was born and raised in Bangu, in Rio’s West Zone. She has a degree in Biological Sciences, a master’s in Environmental Education, and has been a public school teacher since 2006. She is a photojournalist and also works with documentary photography. She is a popular communicator for Núcleo Piratininga de Comunicação (NPC) and co-founder of Coletivo Fotoguerrilha.

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are projects of NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).