This article is part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing #VoicesFromSocialMedia series, which compiles perspectives posted on social media by favela residents and activists about events and societal themes that arise.

On Saturday night January 13, the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region, especially the city’s North Zone and Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense, again experienced the consequences of extreme weather, which is lamentably becoming increasingly common with each passing year. Thus far, 12 deaths have been reported, including three dead due to drowning in Nova Iguaçu, one due to electric shock in Duque de Caxias, and one buried by a landslide in Morro da Pedreira, in the North Zone neighborhood of Costa Barros. Two people are still missing, including hairdresser Elaine Cristina Souza Gomes, 46, who fell from her car in the Botas River, near the municipality of Belford Roxo. The situation showcases the impacts of climate change, which is making extreme weather events more frequent and intense.

Atypical Rain and Garbage Piles are Excuses Heard from Authorities, While Residents Lose Everything

According to Brazil’s National Center for Natural Disaster Monitoring and Alerts (Cemaden), rainfall above 50mm per hour is considered very heavy and deserves special attention. On Saturday, January 13, it rained over 200mm in six hours and almost 240mm over a 24-hour period in the city of Rio de Janeiro. By January standards, this is equivalent to an entire month’s worth of rainfall in a single day, said Philipe Campeão Costa Brondi Silva from the State Environmental Institute (Inea).

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Data from Alerta Rio, Rio’s city-run warning system for heavy rainfall and landslides, show that Anchieta experienced 40% more rainfall than expected for the day. This North Zone neighborhood had the highest recorded rainfall since 1997, with nearly 260mm of rain in 24 hours. While the extent of the rain’s damage is still being assessed, it is reasonable to estimate that it is significant.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

In Niterói, the heavy rain that hit the city over the weekend wreaked havoc on the samba schools’ makeshift shed in Barreto. The site, a former NitTrans vehicle warehouse granted to samba schools by the city hall, saw water levels rising several meters, damaging floats, costumes, and other equipment being prepared for next month’s carnival.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

On the night of January 12, rain displaced drainage pipes throughout the streets of the neighboring municipality of São Gonçalo. Saturday night’s rain left several neighborhoods without electricity, as residents protested against Enel, the energy utility.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

#VoicesFromSocialMedia Say Rio’s Rivers Call For Help

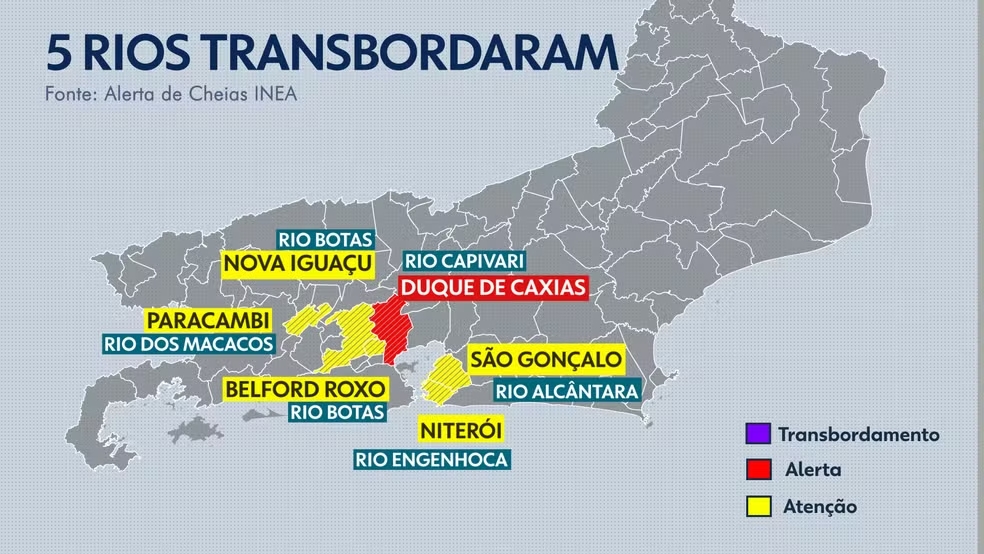

On Sunday, January 14, the Botas, Iguaçu, dos Macacos, Capivari, Acari, Engenhoca and Alcântara rivers all overflowed after heavy rains, leaving residents submerged in the cities of Belford Roxo, Nova Iguaçu, Paracambi, Nilópolis, Mesquita, Duque de Caxias, Rio de Janeiro, Niterói, and São Gonçalo.

Estimates indicate that over 9,000 people have become displaced, and another 300 have been left homeless. In total, over 15,000 people have been affected by the rains in the Baixada Fluminense. Given the scale of devastation, Mayor Rogério Lisboa, of Nova Iguaçu, declared a state of emergency and a state of crisis in the city.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

A video of Viviane Lopes from Jardim Canaã, in the Comendador Soares neighborhood of Nova Iguaçu, has gone viral on social media. In the footage, she is shown standing with water up to her neck. A mother of four, including one autistic child, Lopes expresses her exhaustion with this unyielding strife. According to her, the same thing happens each time it rains. In the video, she laments about the never ending construction on the Botas River, which passes through Nova Iguaçu and Belford Roxo.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The heavy rain that struck Duque de Caxias on Saturday, January 13, flooded many of the city’s neighborhoods. In the neighborhoods of Pilar and Amapá, several streets were completely flooded, making it difficult for vehicles and pedestrians to pass through due to the Iguaçu River’s overflow. In Jardim Primavera, the water rose so much that it covered parked cars on the street.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Despite the relentless sunshine that scorched the city in the days following the storms, several neighborhoods remained flooded. With 130 people now displaced, over 2,000 residents are now registered and awaiting assistance from Duque de Caxias’s city government.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Ver essa foto no Instagram

In the North Zone neighborhood of Acari, residents reported that the water stopped less than a foot short of reaching the roofs of their homes. They lost absolutely everything: furniture, clothes, appliances, food—all earned through hard work. Elderly residents and children are without drinking water and, in many places, also without electricity.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Rio’s Secretary of Environment and Climate Tainá de Paula visited Acari on Monday, January 15, and gave an interview to renowned community newspaper Voz das Comunidades. She expressed solidarity with the victims and explained that the first step is removing the rubble to clear roads and rivers. She asked residents in areas at risk of flooding to pay attention to alerts from authorities and warning sirens, which notify residents when they should leave their homes to safe spots.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

While thousands have been left homeless and displaced in Rio de Janeiro due to the rains, the city hall’s social media accounts posted tips on preventing and addressing the adverse effects of heat, including for pets. Despite the loss of lives, homes, and belongings for thousands who cannot safely return, the city hall prioritizes generic tips, including those for pets, rather than implementing public policies and emergency actions to alleviate the crisis’s impacts.

Dias de muito calor exigem cuidados especiais. Por isso, mantenha-se hidratado, passe protetor solar, use roupas leves e evite atividades físicas ao ar livre no período da tarde. Além disso, se for passear com o pet, prefira as horas mais frescas do dia.

— Prefeitura do Rio (@Prefeitura_Rio) January 16, 2024

Favela organizers, climate activists, journalists, and lawmakers have denounced this pattern of action by authorities in the face of socio-environmental disasters, asserting that it is a reflection of environmental racism, a structural phenomenon. They argue that Black people and vulnerable individuals are systemically pushed into areas of environmental risk, such as steep slopes or areas close to rivers.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Amidst these events, City Councilor Mônica Cunha initiated a discussion on her social media. As the president of the Rio de Janeiro City Council’s Special Commission to Combat Racism, Cunha emphasized the importance of bringing attention to environmental racism and urged public authorities to implement specific and effective measures to combat it.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The fault lies not in the rain but in the absence of sound housing policies, silted rivers, deforestation, inadequate solid waste management, and basic sanitation, lack of environmental education, among many other issues. For example, the Botas River, where Elaine Cristina Souza Gomes remains missing, has been subject to flood warnings for ten years. These are neither new problems, nor are their solutions unknown to public authorities.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Social Inequality, Environmental Racism, and Global Boiling

Raull Santiago, member of the Straight Talk Collective, posted that the planet is in a state of global boiling. For him, there will be no climate justice without guaranteeing the rights of and dignity for favelas.

A study by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV) released in 2022 showed that the Baixada Fluminense is one of Brazil’s poorest regions. The New Poverty Map divided the country into 146 spatial strata. The municipalities that make up the Nova Iguaçu arc, in the Baixada Fluminense, are among the 100 poorest strata. According to the study, 33% of residents in this region had a per capita household income of up to R$497 (US$100) per month in 2021. This means that over a third of the Baixada Fluminense’s population lives below the poverty line. Another region of the Baixada Fluminense, comprised of the municipalities of Duque de Caxias, Magé, and Guapimirim, is also among the 100 poorest in the country. According to the FGV study, 30.48% of these cities’ residents live below the poverty line.

It is important to note that these areas are also among the Blackest in the country. In the Baixada Fluminense, 69% of people identified as Black for the 2022 Census. It is thus no coincidence that this is one of the regions most affected by extreme weather events in Rio.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The Odarah Culture and Mission Collective reinforced the importance of not buying into the narrative that this disaster or damage is due to natural causes. For the collective, what happened is quite obvious: environmental racism, as a consequence of violent, elitist, and racist public management. This serves as a reminder to avoid falling into the fallacy perpetuated by the natural disaster narrative.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Faced with this crisis, the federal government announced the early disbursement of the Bolsa Família (the government’s conditional cash transfer program) to those affected by the weekend’s floods. On Monday, January 16, the nation’s cabinet-level ministers met with the 12 mayors of the affected municipalities and created an emergency office in the state capital and another in the Baixada Fluminense.

Rio’s Governor Cláudio Castro and Brazil’s Minister of Integration and Regional Development Waldez Goés, responsible for Civil Defense, stated that the main objective of the meeting was to listen to the mayors and coordinate resources with the federal government. The meeting, however, took place without the participation of the affected communities, allowing questions only from mainstream media outlets O Globo, G1, Valor Econômico, and UOL, in a spectacle of political theater and, unfortunately, without any representatives from favelas.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The government’s actions will be limited to remedying current problems and, apparently, will not focus on prevention. The governor announced that “there are many contingency and emergency plans for overflows and floods, but it is very difficult to implement them due to the lack of resources and technical expertise. Today’s meeting aimed to cut through this noise, these obstacles. As a practical outcome, Minister Waldez especially, together with the other ministries involved, will leave behind a technical team. This team flew over the Baixada this afternoon and will help in any way possible, especially with expert technicians, in developing plans.”

The focus of the announced actions is to combat floods, not to prevent hillside landslides. However, if the same amount of rain were to fall on densely populated hills, there would likely be dozens of victims buried by landslides. Governments often lack a holistic, comprehensive, and long-term approach. They barely address the current symptoms, much less treat the source of the problem. Furthermore, proposed solutions frequently lean towards engineering, requiring substantial investment and time to materialize—like building more “piscinões” or flood control reservoirs. There is no mention of nature-based solutions and green infrastructure, which are often more accessible and powerful in increasing urban permeability and preventing flooding.

Solidarity Networks Spread to Ease Suffering

In the Baixada Fluminense, collectives organized Unified Baixada, joining forces to help those affected by the floods. The initiative includes Movimenta Caxias from Duque de Caxias, Movimenta SJM from São João de Meriti, the Sim, Eu Sou do Meio project from Belford Roxo, Baixada Lab from Nilópolis, and Casa de Vida Institute from Mesquita.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The Fala Akari Collective is seeking support and generosity to alleviate the suffering of residents affected by the January 2024 rains. Over 30,000 people have been impacted and need assistance.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The Fusion Social Center Association in Mesquita also started a donation campaign for the victims, collecting food, water, clothes, personal hygiene items, and other necessities. Donations can be dropped off at the association’s headquarters at Rua Tamaru, 40 in Jacutinga.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The Lapa Solidarity Kitchen is also a collection point for clothes, personal hygiene and cleaning items, food, water, and furniture. The address is Avenida Mem de Sá, 25, in Lapa from 11am to 6pm.

Ver essa foto no Instagram