Clique aqui para Português

The traditional Acari Fair, which for five decades brightened Sunday mornings around the Acari/Fazenda Botafogo metro station, was abruptly closed on January 22 by Mayor Eduardo Paes, who shared on his social media accounts that, following a conversation with Governor Cláudio Castro, he would issue a decree to prohibit the Acari Fair from taking place on any day. City Hall’s decision was announced less than two weeks after the devastating floods that swept through the surrounding favela neighborhoods, deepening the suffering of thousands who depend on the fair for sustenance. In the same post, the mayor also said: “It is not acceptable that a ‘fair’ replete with products of unknown origin has its functioning normalized by the City.” For the mayor, the authoritarian and simplistic solution to a complex challenge was the extinction of a traditional street market, recognized as an intangible heritage of the city of Rio de Janeiro, which has taken place regularly on Sundays since the 1970s. As a consequence of his arbitrary decision, taken without consulting those affected, February was a bitter and sad month for Acari vendors and residents.

The Acari Fair: A Multifaceted Space in the Life of the Local Community

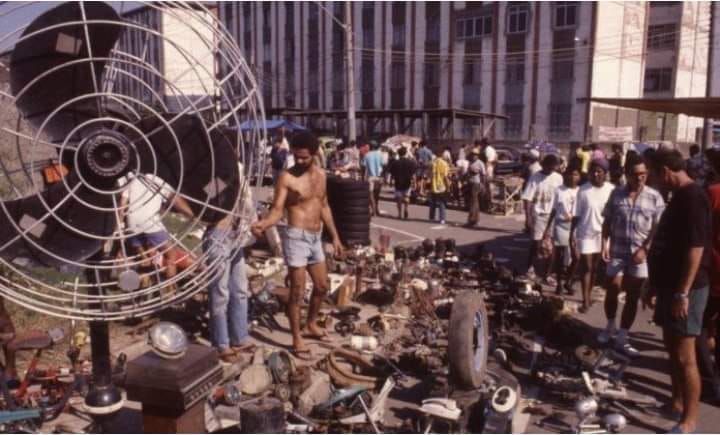

The Acari Fair, immortalized in one of Brazilian Popular Music (MPB)’s most iconic songs, “W/Brasil (Chama o Síndico),” written by Jorge Ben Jor in 1992, in which he melodiously croons, “A Feira de Acari é um sucesso (the Acari Fair is a hit),” is an open-air market that has taken place on Sundays in the neighborhood of Acari in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone for over 50 years. Or rather, it used to—until January of this year. Renowned for offering a wide variety of products at affordable prices, the market served as a vital hub of commerce for the local community and drew visitors from across the city. It was a bustling marketplace where one could find everything, from clothing and electronics to fresh food and personal hygiene products.

In January 2024, the city government of Rio de Janeiro decreed the end of the Acari Fair. The decision happened after a series of police operations at the fair that resulted in the apprehension of counterfeit and contraband items. City Hall’s decision was received with criticism on the part of the local community, who argued that the market was an important source of income for many families in the Acari favela. The Acari Fair is also regarded as cultural heritage by the community, and its closure represents a significant loss.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

“Eliminating the Acari Fair in response to isolated and criminalizing allegations is a simplistic attempt at a solution, as well as being morally hygienist, elitist, and racist towards a complex problem. Instead of drastic prohibition, it would be more beneficial for the region to explore cooperation strategies between regulatory authorities and the vendors themselves to ensure the continuity of commerce. Banning the fair not only affects the vendors but also harms residents, who depend on this reliable source of accessible products.” — Fala Akari Collective

Letícia Pinheiro, resident, social worker, Master’s student, and active participant in the Acari Agenda 2030 and Fala Akari collectives, recounts how two major floods, occurring consecutively within a week, impacted the favela. In certain locations, the water reached three meters. Many families had their residences flooded twice. Shortly after came the notice of the fair’s prohibition by City Hall.

“The method of criminalizing the fair exemplifies extremely specific features of how City Hall views peripheries and favelas. We know this would not happen at fairs in South Zone locations, for example. If there is an irregularity or some other issue, we must think through the path together. How will we regulate the fair and regularize the vendors? Often, self-employed workers are there without any type of assistance. City Hall’s first measure was prohibition. It’s a terrible and routine characteristic of the State’s actions in the favelas.” — Letícia Pinheiro

One of the parliamentarians from the Rio de Janeiro City Council to take a stand was Councilwoman Thais Ferreira, who spoke against banning the market. She suggests more oversight in place of prohibition.

“During a moment when Acari is grappling with the impact of summer rains due to a deficit of public policy, the Acari Fair, recognized as intangible cultural heritage of the city, is threatened by City Hall with a justification that further highlights the absence of authorities in guaranteeing basic rights to the population of this area. If the issue is unknown products, let there be oversight!” — Thais Ferreira

‘Acari Weeps’: An Act for the Return of the Cultural and Intangible Heritage of Rio

Two peaceful protests occurred when the Acari Fair was banned. The first took place at around 8:15am on January 28 itself, the same day of City Hall’s operation to shut it down. Vendors and residents gathered at Avenida Martin Luther King Jr., near the Acari/Fazenda Botafogo metro station. Protesters cried out, “We want to work, we want to work,” and carried signs with messages like “Rain, death, floods, and the end of our fair: Acari weeps.” The second protest took place on the following day (29), after an assembly called and carried out by the fair’s workers.

Declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of the City of Rio de Janeiro by Law #7.468 passed on July 14, 2022, the Acari Fair is symbolic. It is a cultural representation of how favelas organize and devise their own survival strategies. Even with the urban dynamic of inequality and violence in the region, the fair has survived for over 50 years. Its banning impacts many families and has far-reaching consequences for the local economy.

“The end of the fair directly impacts the local economy. We’re talking about vendors, here. The better part are residents of Acari favela or neighboring areas, who sustain themselves through the fair. It was prohibited without any type of prior dialogue with the population, without considering an alternative structure for the fair. This directly harms the local economy and many in this population, which, as a matter of fact, suffered from the floods.” — Letícia Pinheiro

Dona Maria Paula,* a vendor and resident of Acari, has worked for over 35 years at the neighborhood fair. She ran a secondhand shop and earned, on average, R$15-R$20 (~US$3-4) per day. She expresses her disbelief, stating that she never imagined the fair could be prohibited:

“I, honestly, don’t know what to say. I’m at a loss for words. I live on a minimum salary and work with secondhand items at the fair, which supplemented my income… What are we supposed to eat until payday? This fair was very useful for me. Now only God knows what I’m going through. I have to buy food for my pets, who are running out of food. This fair was everything—God in heaven, and it on Earth. It was my bread and butter.”

Even with the Fair Prohibited and Acari Devastated by Floods, Hope Remains

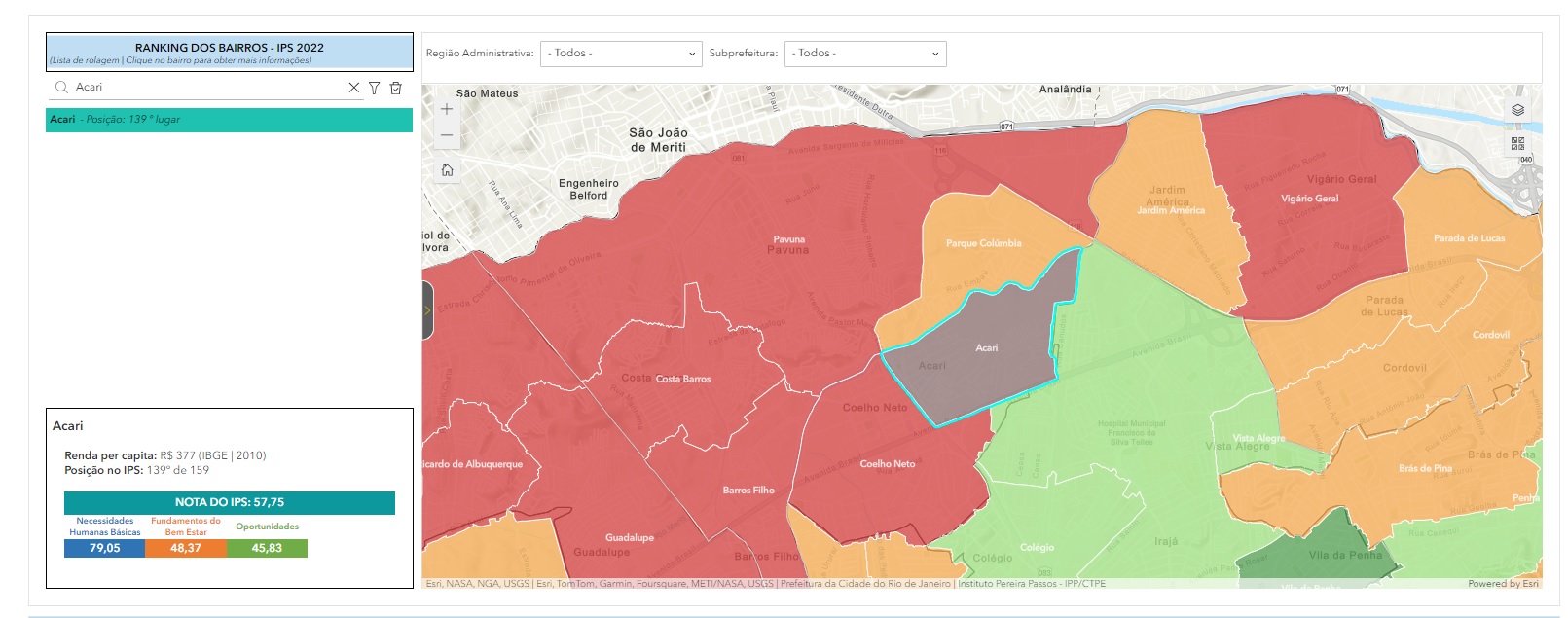

Acari has the third-lowest Human Development Index (HDI) in the municipality of Rio and the second-lowest income levels. In 2000, its HDI was 0.720, ranking it 124th out of 126 regions of the city. It also ranked 139th among the 159 neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro in the City of Rio de Janeiro’s Social Progress Index (IPS), with a score of 57.75 and a per capita income of R$377 (~US$76).

Councilwoman Thais Ferreira stated that she proposed a series of legislative recommendations and submitted a request for information regarding the fair’s situation. Additionally, she is engaging with vendors and fair visitors to hear their priority demands arising from the circumstances outlined in the decree.

“We have proposed a Legislative Decree to suspend the effects of the mayor’s decree… Law #7.648 [which declared the Acari Fair as city heritage] will serve as a crucial foundation for the legislative decree project to overturn the mayor’s decree, as the law promotes the appreciation of the Acari Fair rather than its extinction.” — Councilwoman Thais Ferreira

Pinheiro explains that, unlike City Hall, local social collectives and movements, such as Acari Agenda 2030, have developed numerous strategies and public policy plans for the Acari Fair, its vendors, and customers, always considering it as both an economic and cultural asset for the neighborhood and the city.

“After the ban, there was some dialogue with a few vendors… One of the strategies focuses on recognizing value in the Acari Fair. While it’s already recognized as part of Rio de Janeiro’s heritage, this doesn’t provide protection for the vendors or prevent actions like those taken by City Hall… We see the fair as more than just a place for Acari residents, for the people who have access to it on a day-to-day basis. I, for instance, am the third generation in my family to frequent the Acari Fair. It’s a cultural reference, a place with a rich history. That serves as a crucial foundation for us to consider any actions regarding the fair.” — Letícia Pinheiro

On January 31, the North Zone Subprefecture met with some workers from Acari Fair. In a publication, Deputy Mayor Diego Vaz commented on the meeting.

“At the request of Mayor Eduardo Paes, I met with a group of workers from Acari who wish to formalize their situation and sell legally-sourced products. The idea is to integrate these workers into an existing fair in the area, where they can sell their products following the model of the Basilio de Brito Fair and the Gloria Fair, among others.” — Diego Vaz

Until the time of publication of this article, there is no possibility, according to City Hall, of the Acari Fair returning. Having been without work for weeks, Maria Paula* waits for contact from the city government and still holds on to hope for the market’s return:

“On January 26, I and a bunch of people went to the North Zone Subprefecture. There was an enormous line, with a lot of people there. They asked for my name, contact number, and inquired about the merchandise I worked with… They want to relocate us to another fair, but so far, nothing. No one has been relocated, and I’m still waiting for the contact. You can’t imagine how sad I am, very sad. God knows what I’m going through. But still, I have faith. I have faith that this fair cannot end. Yes, it will return, it may take time, but I have faith in God that it will return.”

Ver essa foto no Instagram

*The name of the interviewee is fictional, to preserve the identity of the resident and vendor.

About the author: Felipe Migliani has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Investigative Journalism. Working as an independent journalist and freelance reporter at Meia Hora and Estadão newspapers, he also collaborates with the Coletivo Engenhos de Histórias, which investigates and recovers history and memories from the Grande Méier region, and with PerifaConnection.