Clique aqui para Português

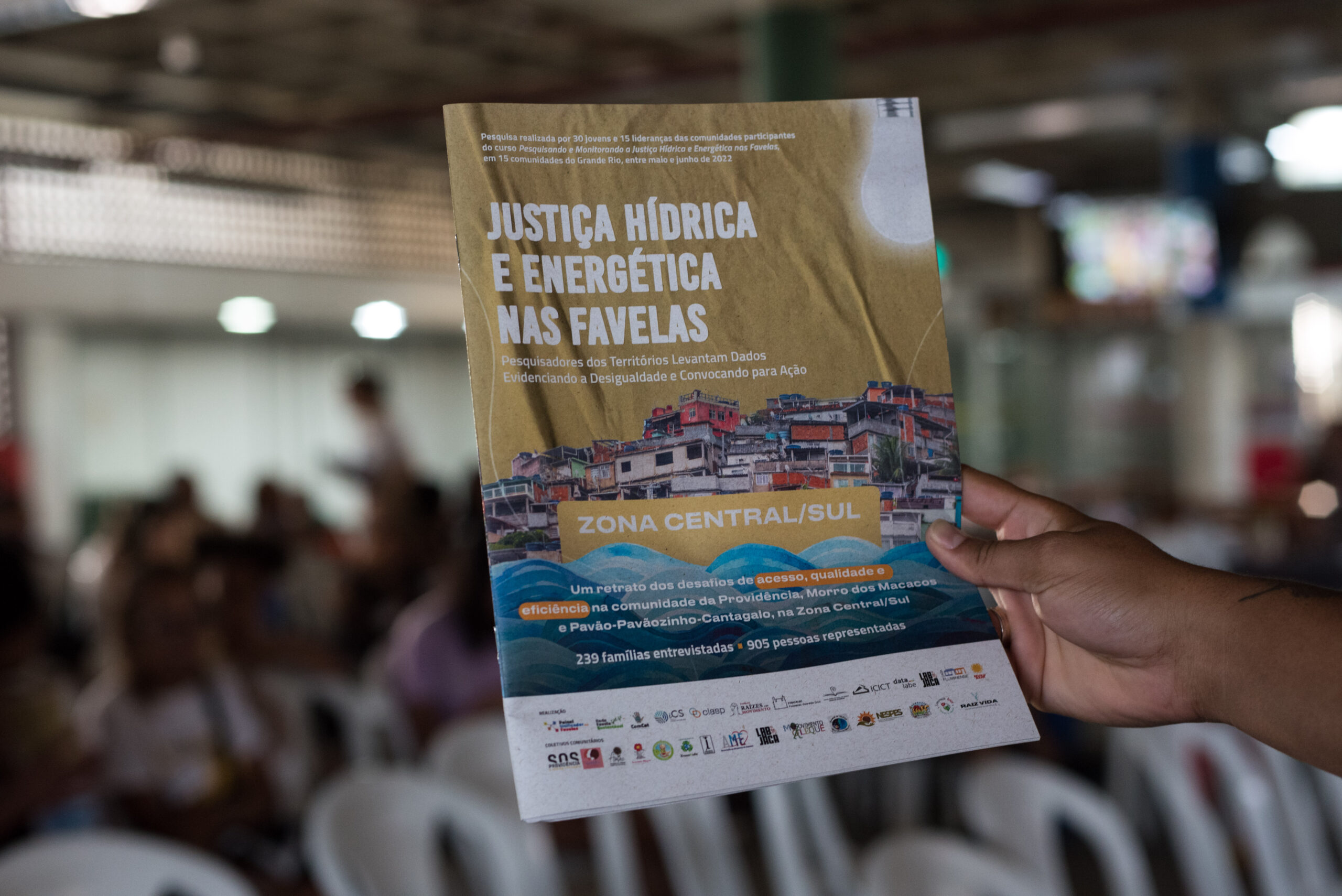

March 18, 2024—Last month, communities affiliated with the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN)* and the Favelas Unified Dashboard (PUF)* held the final local data launch from the report “Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas: Community Researchers Gather Data Revealing Inequalities and Calling for Action” at Galeria Providência. The communities contemplated in the final event were: Providência in Centro; Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo (PPG) in the South Zone; and Complexo da Pedreira and Morro dos Macacos in the North Zone. The data were gathered during the course “Monitoring Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas,” in 15 favelas of Greater Rio throughout 2022 and engaged 30 youth and 15 community leaders from 15 favelas across Greater Rio: in the city of Rio de Janeiro, these included City of God, Complexo da Pedreira, Itacolomi, Jacarezinho, Morro dos Macacos, PPG, Providência, Rio das Pedras, and Vila Cruzeiro; in the Baixada Fluminense, they encompassed Coréia, Cosmorama, and Jacutinga in Mesquita; Dique de Vila Alzira in Duque de Caxias; Éden in São João de Meriti; and Engenho in Itaguaí.

Data on Water and Electricity in Four Favelas, Launched at Final Event of its Kind

The local data launches of the report “Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas: Community Researchers Gather Data Revealing Inequalities and Calling for Action” held throughout 2023-2024 in the 15 communities that were surveyed by the Sustainable Favela Network, go against the grain of what typically happens once data are collected. Instead of focusing immediately on presenting the research to government officials and decision-makers, or storing it in libraries and archives, the focus was on returning to the communities surveyed, debating the results, enhancing knowledge, and strengthening access to information for the local population, so that together residents can come together, informed, to advocate for their rights.

The launches were moments of intense exchange between young researchers, community leaders, and residents, with the final event on February 24 launching local data to residents of Providência, PPG, Macacos, and Pedreira favelas, with several other communities also present. In their communities, young researchers identified the challenges faced by residents regarding water and electricity provision by private utilities Águas do Rio (water) and Light (electricity), revealing an alarming lack of quality access to these services. Testimonials at the launch event made it clear that there has been a deterioration in services rendered since the research was conducted in 2022, with particular emphasis on water access and quality.

Research By and For the Favelas

When government neglects its responsibility to conduct research that is needed to inform the provision of basic services, who is left to do the work? In yet another domain, it is the “by us for us” approach that offers the only way out for favela residents. It is up to residents themselves to self-organize and generate their own research. This is how the report “Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas” came about.

“Historically, we fought with the resources we had, but I think that being able to fight in this manner [with data] gives us a different advantage. Having information and data about the place where we live adds a factor of dignity and respect that puts us in a different light [when fighting for rights].” – Hugo Oliveira, Galeria Providência

The data from the report, in general, reveal that water is more scarce in Rio’s favelas than previously understood, relying on pumps and water tanks to ensure access. The data on electricity is equally concerning in the context of climate change, especially when accessing water requires electricity. Among other issues, many residents are not served by Light, the electric utility, and when they are, cases of abusive billing are frequently reported, along with blackouts, power surges, equipment damage, and days-long power outages.

Testimonials of Abuse Set the Tone of the Event

The majority of testimonials by residents at the launch shed light on the deteriorating access to water since the 2022 research was conducted, just after Rio de Janeiro’s water access was privatized. From issues with water supply and quality to leaks, unaffordable bills, and unresponsiveness from private utility Águas do Rio, a range of concerns were raised. Similarly troubling were the findings regarding electricity, with many residents unable to access assistance from Light, reporting exorbitant charges, and enduring frequent blackouts and power surges that damage equipment.

A resident of PPG noted a significant decline in water service following the privatization of public utility CEDAE, now private utility Águas do Rio.

“We’ve noticed a major issue with supply, with increased waste, since Águas do Rio uses low-quality materials. In many cases, besides waste and water shortages, we’ve noticed that the numbers [in the report] have worsened. Personally, I’ve experienced water shortages due to Águas do Rio’s failure to provide adequate supply.”

Another PPG resident, a craftsman, explained that the water rotation schedule set by the utility does not always manage to supply everyone in the favela.

“When it comes to this [supposed] rotation schedule, it ends up that not everyone gets water [since there is already a three-day waiting period for the normal supply].”

Letícia da Silva, from Providência, recounted the deterioration in water delivery to her home following the privatization of CEDAE.

“The water situation is dire! For us to have access to water, people wake up at dawn to fill up every vessel, wash dishes, and do the laundry. By around six in the morning, there’s no water left. We have to sit and wait; there’s very little water… Then we get our children ready to go to school. There’s also no water at the school… So, you have to find someone to take care of the children, so you can search for or go to work and do your daily errands… After the new company entered the market, we no longer have water, at least not on my street and at my daughters’ school…”

Other residents continued to report that access to water had significantly worsened under the new utility, with inefficient distribution, even in the lower parts of favelas—a situation that did not exist previously. There were also reports of increased water bills and wrongful charges.

Concerning water meters, residents of Complexo da Pedreira reported that 96% do not have the equipment, while in Morro dos Macacos, the figure is even higher, reaching 99%. A resident of PPG shared her experience of having a water meter at home and paying bills promptly, yet still facing threats of water being cut off by the utility.

“I’m from PPG, we have a water meter at home, but we still face many problems. They often come by saying they’re going to cut off our water supply, even though we pay our bills on time. And still we’re having this problem with them coming by and saying they’re going to shut off the water. Then we have to run to the [Residents’] Association to prove our payments. I think this shows how disorganized Águas do Rio is… sometimes, we go a week without water even when we’re paying for it.”

In Providência, residents voiced complaints about the installation of water meters leading to unjustified charges. Access to water deteriorated under the new utility, including in areas previously unaffected by frequent water shortages, such as the lower parts of the favela.

“Back when it was CEDAE, we had these kinds of issues, but they were minimal, very little. But after Águas do Rio took over, I live in a lower part of the community, and at my house, on many days, the water pressure is very low. I have two 1,000-liter tanks, and many times, when I realize it, my water is running out. My mother also lives in a place with six houses… it’s like a row of houses… When it was CEDAE, the bill there was R$700 [US$141] split between six houses. Now, the water runs out, but the bill remains the same… In my house, with a water meter installed, there are days when the water flow is weak, so the meter readings should be lower, right? Because there’s less water coming in… Águas do Rio came in, but there haven’t been any benefits to the residents, no pipe replacements, no support, and we’re still paying [without receiving decent service].”

Seeking their rights, some residents turned to the courts to address wrongful charges and poor service. One resident recounted that she lives in section where two residences were demolished due to structural problems. However, to everyone’s surprise, instead of the reduced number of homes decreasing the collective water bill, which averaged R$700 [US$141], something unexpected happened: it nearly doubled.

“To our astonishment, the bills started coming in at R$1,200 to R$1,300 [~US$240-US$260], so we went looking for knowledge, for our rights, because we are fulfilling our duties… We went to Águas do Rio, took photos when the houses started being demolished, we demonstrated, sent emails… [To] our surprise, they said that would be the same amount charged, and therefore, we had to take legal action… We’re not ashamed [to say] we have 13 unpaid bills, we’re in court, fighting for our rights.”

There were reports of water meter being installed without residents being home. Furthermore, local digital influencers and residents are hired to work for Águas do Rio, leveraging their knowledge of the neighborhood. This tarnishes the local social fabric, promoting a kind of “neighbor finger-pointing” to the company, causing mistrust and division among residents.

“They hired residents of the favela, people who needed work. These folks know the ins and outs of everyone’s lives. They go knocking on their neighbors’ doors and say, ‘Hey, you’ve got one water meter, but there are three families living here, so you’ve got to pay three fees.'”

The data on access to electricity, quality of service, and efficiency revealed another alarming statistic: 56% of respondents are living in energy poverty. This means their electricity bills consume over 10% of their monthly family income, exceeding the maximum recommended amount of 7%. Among those affected, 69% reported that if they didn’t spend as much on their bills, they would allocate more funds toward food.

“In the upper part… some residents haven’t had power for a whole week. Our electricity was acting up yesterday, flickering on and off, not even keeping the light bulbs on. Can you imagine enduring this heat without a fan? I’ve got three little ones at home, and we can’t get any sleep. As a result, everyone’s exhausted the next day—kids have to go to school, I need to go to work, and my husband too. It throws the whole day off. Unfortunately, that’s how it’s been, and it gets even worse in summer.”

Electricity and water are connected: without electricity, there are no pumps to ensure access to water, which comes inconsistently, to maintain livable spaces in the heat, and on top of that, the electric bill contributes to food insecurity.

With the data presentation coming to a close, leaders from the surveyed favelas put forward proposals to achieve water and energy justice. These included establishing on-site community posts where water and electricity services are rendered, providing financial assistance for purchasing pumps, trading in inefficient appliances and light bulbs for more energy-efficient versions, as well as the utilities employing local plumbers and electricians.

Don’t miss the photo album by Bárbara Dias on Flickr:

About the author and photographer: Bárbara Dias was born and raised in Bangu, in Rio’s West Zone. She has a degree in Biological Sciences, a master’s in Environmental Education, and has been a public school teacher since 2006. She is a photojournalist and also works with documentary photography. She is a popular communicator for Núcleo Piratininga de Comunicação (NPC) and co-founder of Coletivo Fotoguerrilha.

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN), Favelas Unified Dashboard (PUF), and RioOnWatch are projects realized by not-for-profit organization Catalytic Communities (CatComm).