This article is part of RioOnWatch‘s series on Memories of Favela Power, which documents and celebrates the history of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas through narratives and reports from residents’ collective memory, in their daily struggle to lead fulfilling lives.

The Historic Invisibility of Favelas and Their Necessary Centrality

Comprised mainly of military heroes and governing authorities, Brazilian History conceals favela residents and any other racialized group. Favelas have the right to memory and, more importantly, need to be recognized and valued for their central role in the workings of the city of Rio de Janeiro. They sustain our economy and development. We are all positively affected by the wealth generated by and in favelas. And above all, the favela is an asset in the people’s fight for housing, against a century-old housing crisis.

It is in this context of struggle and resistance, that a people’s memories are experienced and produced. To preserve some of these memories, workers studying during a literacy night class for youth and adults decided to write a collective book documenting their recollections. Written between 1978 and 1983, during Brazil’s Military Dictatorship, the book Varal de Lembranças: Histórias da Rocinha [String of Memories: Stories from Rocinha] still serves as a reference for the retrieval and recording of local memory.

The work built and documented new historical narratives from the voices of favela residents during the dictatorship. Under an authoritarian regime, the emphasis on ordinary stories lived by individuals in the favela was revolutionary and democratizing.

A social studies project conducted with students from the Youth and Adult Education (EJA, as the Brazilian acronym is known) program of Ação Social Padre Anchieta (ASPA)’s night school culminated in the creation of Varal de Lembranças. This was the first book published by a favela collective and is a unique artifact, a reference in Brazilian history. Working with EJA students means recognizing the power that school can exert in the lives of these students—who are mothers, fathers, and workers before being students. The school aimed to be an instrument for minorities to tell their own story and a means to build new foundations for education and the preservation of favela memory and heritage.

However, writing, editing, and publishing a book is a long and expensive process. The students thus decided to submit their project to the National Center for Cultural Reference (CNRC/IPHAN), which issued calls for proposals from legal entities that valued regional diversity. To be eligible, the application had to be submitted by a legal entity: the organizations that took on the project were the Rocinha Pro-Improvement Union (UPMMR) and the Rocinha Residents’ Association.

The Story of Varal de Lembranças: Histórias da Rocinha

Having previously prioritized subsistence over formal education, a group of workers found themselves in an EJA class at the height of the dictatorship. Together, they embarked on the task of imagining how the history of Rocinha could be told from the memories of its residents and in their own words. They were motivated by the complete absence of works and authors that represented the favela, written by and for favela residents. All they found about themselves in the literature available, especially textbooks, was silence.

“We realized that there was little or almost nothing on the history of workers and the favelas.” — Varal de Lembranças: Histórias da Rocinha

Thus, the embryo of the book emerged. The actual process of literary production began in 1978, in the social studies classes of Ação Social Padre Anchieta night school’s graduating class. Right from the outset, the work offered an unprecedented perspective for the time, providing novel approaches and sparking discussions on the memory and identity of favela populations.

A book published by students from a favela night school, in partnership with the Residents’ Association, proved that democracy was possible by contradicting the stereotypical and stigmatizing hegemonic narrative on favelas—a narrative that continues to resonate in phrases like “favelas don’t make writers. They make thieves, rapists, and vagrants,” as documented by Carolina Maria de Jesus in her book I’m Going to Have a Little House: The Second Diary of Carolina Maria de Jesus, published in 1961. Associated with the myth of marginality, working-class spaces are not recognized for their literary or cultural potential. Culture is not expected to flourish in such places.

The students’ experience in creating the book unfolded in three phases. The first involved how the class itself came together: individuals with no apparent connections, united by the pursuit of delayed literacy in the night school system. The second phase was the “reading” phase, which included both textbooks and fragments of their own lives. This phase involved recognizing a deficient history that had not yet been told and needed to be documented. The third phase was the daring act of cataloguing different accounts of life in the favela for publication. Despite the divergent narratives presented, the residents got to work and began writing the book.

Favelas have already been the subject of numerous approaches and studies: hygienic or anthropologized; praised or denied; evicted or upgraded. This might even be one of the factors that has, over time, contributed to a better understanding of what favelas are and of the structural racism and denial of the right to housing that are ever-present in Rio’s urban space. As Adair Rocha, a professor at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), states in his book Stitched City: The Sewing of Citizenship in the Santa Marta Favela, “the favela is at the root of the Brazilian social issue, a legacy of slavery, whose unequal and hierarchical treatment marks the construction and maintenance of the city and of society.”

The Right to Memory in Times of Darkness

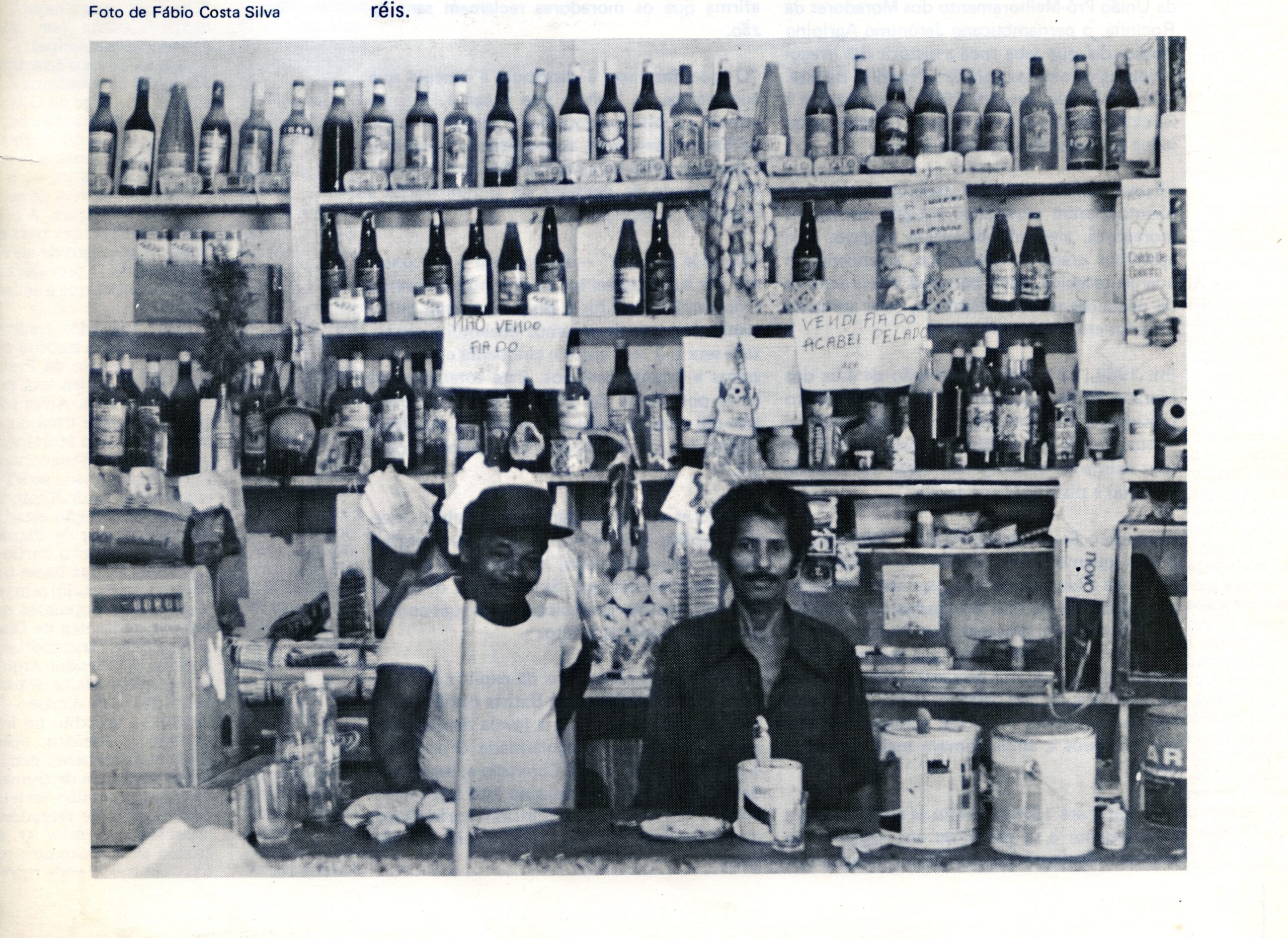

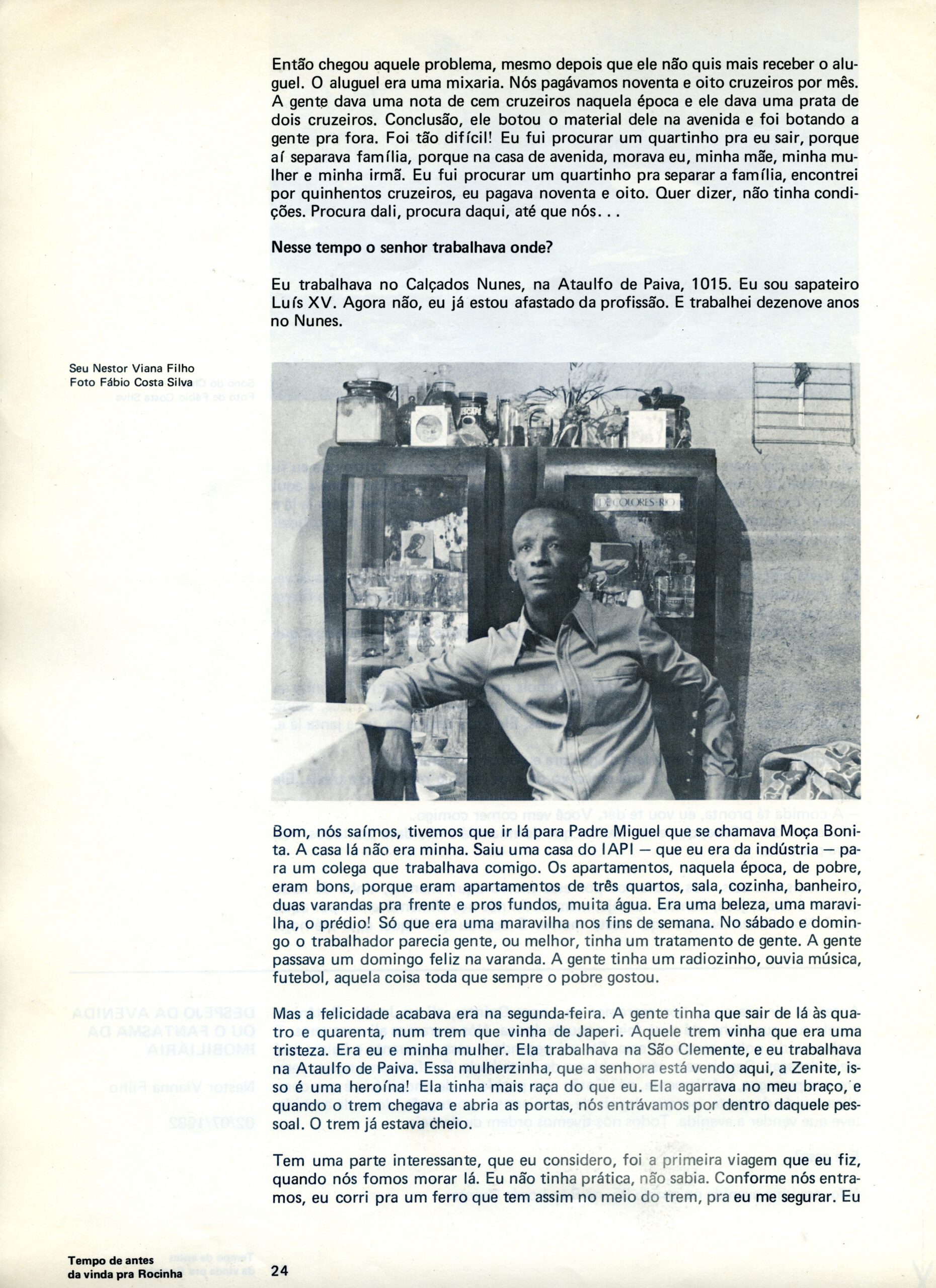

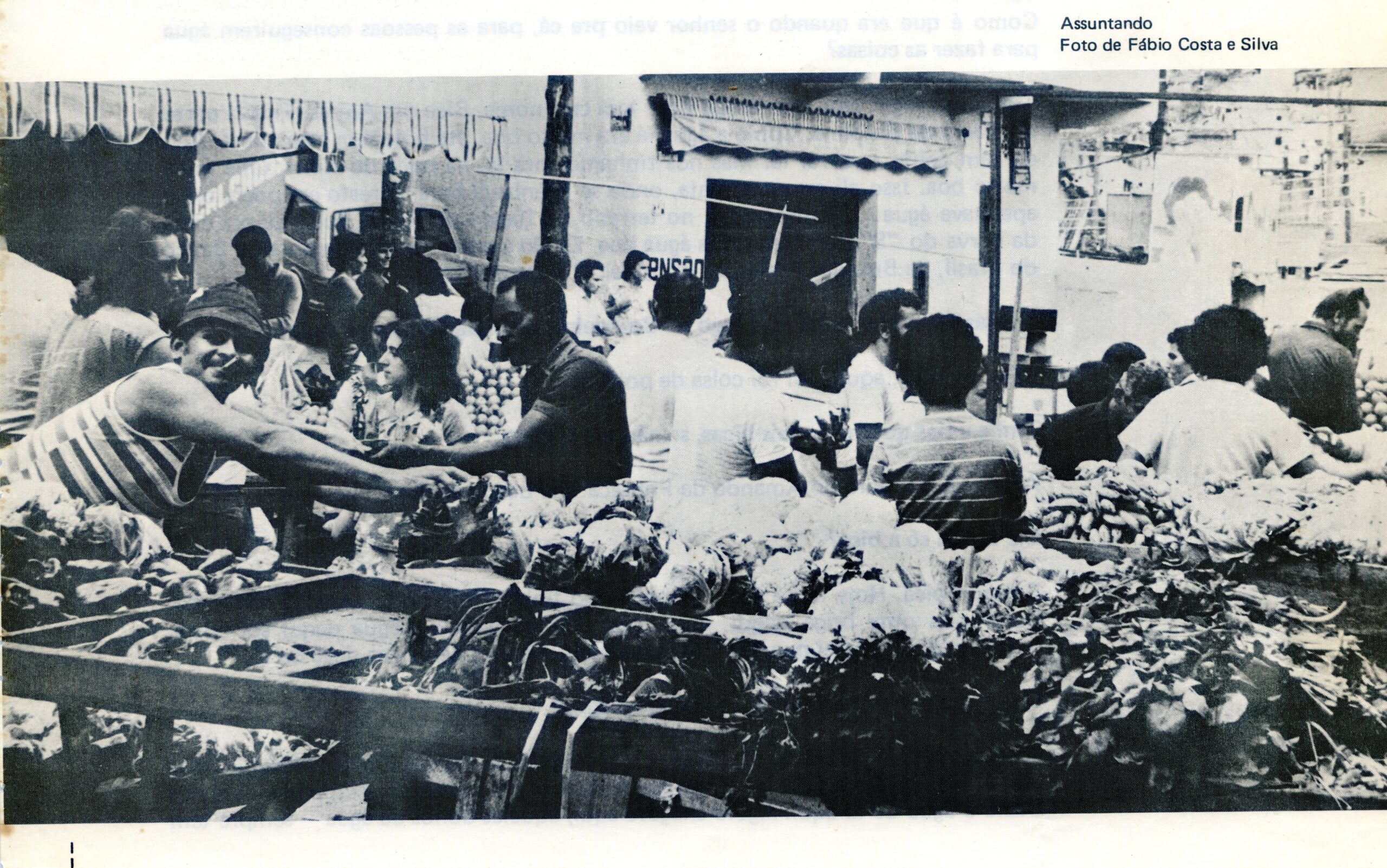

Published in 1983, Varal de Lembranças: Histórias da Rocinha was the result of an exercise in building self-image by a group of students from a youth and adult education program in Rio’s largest favela, which until recently held the title of the largest favela in Latin America. The team consisted of teachers, community educators, photographers, members of the residents’ association, representatives from community centers, and individuals interested in local history. They drew upon sources such as fragments of letters, photo albums, poems, flyers, samba lyrics, newspaper clippings, and, of course, the students’ own memories. They stitched together memories and keepsakes to create a book.

Signing up for the night literacy course for youth and adults was the path found by workers who had to prioritize their subsistence over the course of their lives and, as a result, did not finish school or attend regular classes at the “standard” age. These students worked and studied during the week; they were cooks, salespeople, typists and more. Awakened in their cultural role as author-residents of Rocinha, these socioeconomically marginalized individuals embraced the challenge of thinking and writing their own memories and experiences. Through active listening, they also collected the perspectives of other residents of their favela. Together, they wrote a book with the history they realized was missing from bookstores and libraries.

About the Author: Fernando Ermiro da Silva was born and raised in the Rocinha favela. A doctoral student in the Social Memory and Cultural Heritage Program at the Federal University of Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, he holds a Master’s degree in History, Politics, and Cultural Assets from the Getulio Vargas Foundation and a Bachelor’s degree in History. He is a Coordinator of Rocinha’s Sankofa Museum of Memory and History, editor of the book “Tales from Rocinha: Female Memory in Three Tempos,” and author of the children’s short story “Vacations, Kites, and a Java Plum Tree” by the Besouro Literary Collection.