“Of course we’re talking about much more than a sporting event,” stated Orlando Santos Junior. “We are talking about a city project, a project of urban re-structuring which deserves to be discussed by society, by all of us.” He argued that the series of interventions taking place in preparation for next year’s World Cup and the 2016 Olympics reflect a broader vision of Rio de Janeiro—one that expels the poor to the periphery of city.

“Of course we’re talking about much more than a sporting event,” stated Orlando Santos Junior. “We are talking about a city project, a project of urban re-structuring which deserves to be discussed by society, by all of us.” He argued that the series of interventions taking place in preparation for next year’s World Cup and the 2016 Olympics reflect a broader vision of Rio de Janeiro—one that expels the poor to the periphery of city.

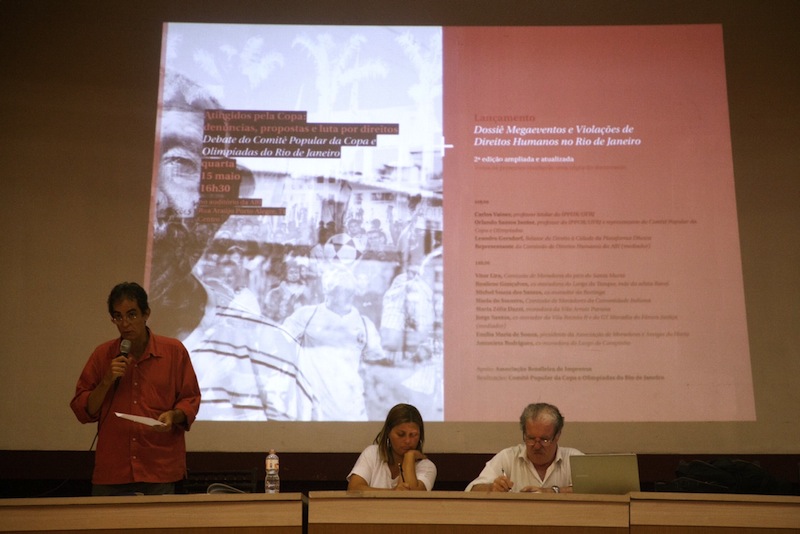

Orlando, a professor at Rio de Janeiro Federal University’s (UFRJ) Urban and Regional Planning Research Institute (IPPUR), and researcher at the Observatório das Metrópoles (Metropolises Observatory), was speaking before an audience of several hundred people from diverse social movements and communities who gathered on Wednesday May 15th for the launch of the second Mega-events and Human Rights Violations Dossier by the Rio de Janeiro Popular Committee for the World Cup and Olympics.

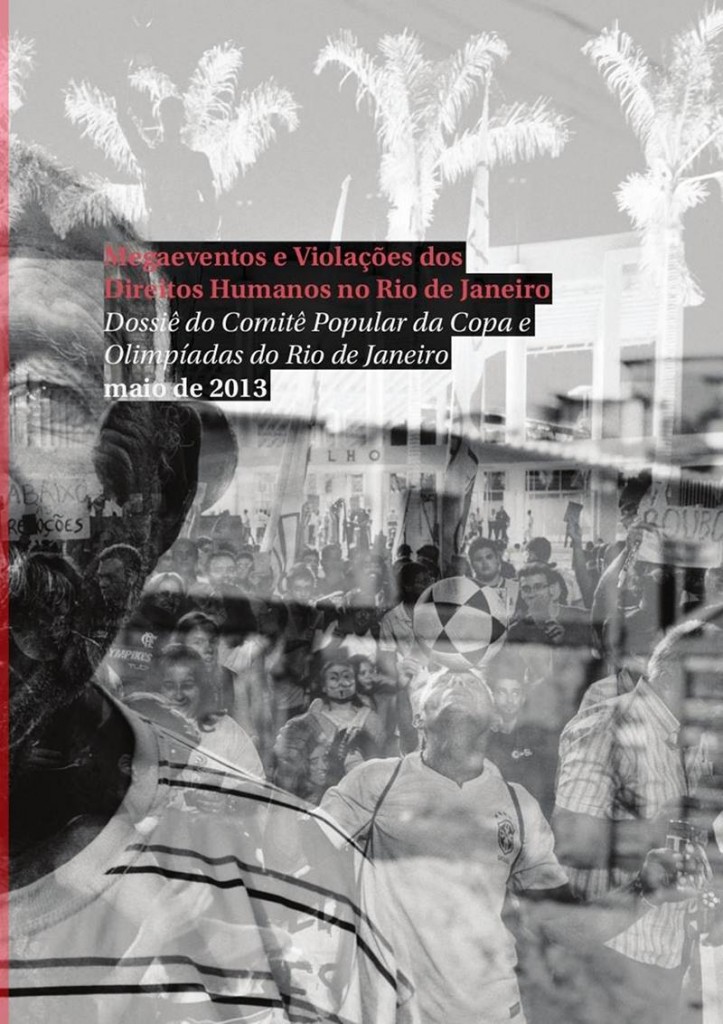

The excitement in the room was palpable as Orlando presented the impressive 130-page publication, which documents human rights violations taking place across the city in conjunction with (or under the guise of) mega-event transformations. This updated dossier expands upon an earlier version published in Rio de Janeiro in March 2012. A national collaboration between all the Popular Committees (Comitês Populares in Portugese) was published in 2011.

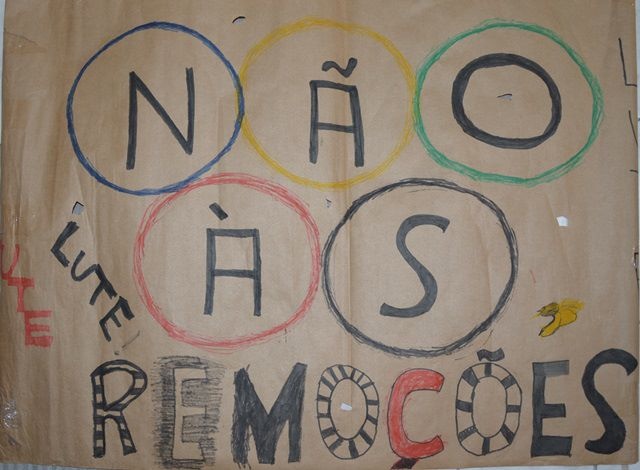

The dossier shows that preparation for these mega-events in Rio de Janeiro extends beyond upgrading sports facilities and transportation infrastructure. The document illustrates both a reconfiguration of the built environment and shifting socio-political power structures in ways that benefit the elite at the expense of the urban poor. Forced and arbitrary evictions, lack of transparency and democratic participation, shifting institutional arrangements as power is subordinated to FIFA and the International Olympic Committee, and the militarization of poor communities, are all part of an ongoing process of ‘limpeza social’ (‘social cleansing’) which delineates who has access to the city of Rio de Janeiro.

The dossier shows that preparation for these mega-events in Rio de Janeiro extends beyond upgrading sports facilities and transportation infrastructure. The document illustrates both a reconfiguration of the built environment and shifting socio-political power structures in ways that benefit the elite at the expense of the urban poor. Forced and arbitrary evictions, lack of transparency and democratic participation, shifting institutional arrangements as power is subordinated to FIFA and the International Olympic Committee, and the militarization of poor communities, are all part of an ongoing process of ‘limpeza social’ (‘social cleansing’) which delineates who has access to the city of Rio de Janeiro.

The launch was comprised of two panels. During the first, Orlando Santos Junior presented the main themes of the publication; he was followed by urban planning professor Carlos Vainer who described the concept of “state of exception,” in which traditional democratic and decision-making processes are suspended or circumvented, the right to information is denied, and human rights are “systematically and regularly violated.”

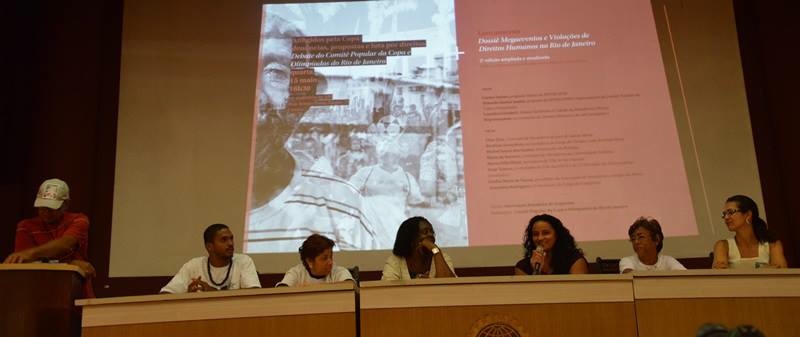

In the second panel, representatives and leaders from different communities discussed their experiences being forcibly removed or their ongoing efforts to resist removal.

Both panels illustrated a key point made by Carlos Vainer: “We are facing permanent and systematic violations of […] fundamental rights, without which the word ‘democracy’ becomes a farce.”

Lack of Information, Participation and Transparency

Orlando devoted significant time to a discussion of forced evictions, a practice that has intensified since the Comitê Popular’s first publication, arguing that people are not being given any opportunities to discuss or participate in what is instead a violent and coercive process.

The Dossiê summarizes the history of each community removed or threatened with removal, the past and ongoing resistance efforts in these communities, and the city’s justification for their removal, which include transportation infrastructure works, installation or reform of sports venues, “revitalization” of the port area, and “area of risk” or environmental interest.

To date, 3,099 families have been removed and another 7,843 families are currently under threat of removal in Rio de Janeiro (see chart).

Orlando also argued that there is an important geographic component to these forced evictions; communities are being removed from areas of high real estate appreciation (South Zone, Port Region and Barra de Tijuca) and are primarily being resettled in the far West Zone. In other words, there is a process of relocation of the poor to distant peripheral areas, which is linked to a broader project of real estate speculation more than it is a necessity for the realization of the events.

Orlando also argued that there is an important geographic component to these forced evictions; communities are being removed from areas of high real estate appreciation (South Zone, Port Region and Barra de Tijuca) and are primarily being resettled in the far West Zone. In other words, there is a process of relocation of the poor to distant peripheral areas, which is linked to a broader project of real estate speculation more than it is a necessity for the realization of the events.

Human rights violations are closely related to the restriction of information and lack of transparency, as the speakers showed. Carlos pointed to the corrupt relationship between the government, media and private interests that collectively work to control information at the expense of the city’s poor communities. “[There is] not only a lack of information; there is a systematic, organized, and deliberate politics of disinformation.”

Carlos presented the story of Vila Autódromo—the city’s most visible example of ongoing resistance to eviction—to illustrate this practice of disinformation, as the city has used an array of justifications in its efforts to remove the community: environmental interest, area of risk, security perimeter for Olympics, media installation, and so on.

Running in tandem with lack of transparency and the absence of public participation are what the dossier refers to as “new institutional arrangements,” in which democratic processes and existing legislation are subordinated to the interests of FIFA, the IOC, and their subsidiaries. Orlando pointed to the World Cup Law (no. 6363) passed in Rio state last December which lays out a series of restrictions during the World Cup and Olympics extending far beyond the realm of the sporting competitions themselves such as control of meetings and conferences related to FIFA, changing the school calendar, control of sale of goods and services in stadiums and in extensive perimeter and control of exclusive rights.

These restrictions, many of which contradict federal legislation, effectively “transfer the power to legislate to FIFA and to the IOC,” Orlando stated. The dossier summarized the law as “an expression of a certain pattern of public authority intervention, marked by authoritarianism and exception… [giving over to FIFA and the IOC] the power to manage public spaces directly or indirectly affected by the realization of these mega-events.”

These restrictions, many of which contradict federal legislation, effectively “transfer the power to legislate to FIFA and to the IOC,” Orlando stated. The dossier summarized the law as “an expression of a certain pattern of public authority intervention, marked by authoritarianism and exception… [giving over to FIFA and the IOC] the power to manage public spaces directly or indirectly affected by the realization of these mega-events.”

In his presentation, Orlando briefly elaborated on other sections of the dossier including mobility and how transportation networks link central areas; jobs and the city’s removal of informal workers and street vendors; sport, arguing that the privatization and renovation of Maracanã stadium has radically altered its “popular character;” environment and how the discourse is used to legitimize arbitrary removals; and public security, in particular the high public cost of security apparatus for the events, in addition to ongoing costs and violations by Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), BOPE, and Shock Police.

Communities Under Threat

During the second panel, representatives and community leaders from across the city spoke about their experiences of being removed from their homes or their resistance efforts in response to the threat of eviction.

Vitor Lira, a resident of Santa Marta, juxtaposed the decades of abandonment by the government with the current transformation of the community into “Disneylandia” since pacification. He argued that Santa Marta has become “a business territory,” with both real estate and tourist interests entering to exploit the favela for profit. At the peak of Santa Marta, the city has marked 150 homes for removal, citing area of risk; Vitor and others argue that it is part of an ongoing effort to increase tourism. The removal attempt highlights what Vitor referred to as the “arbitrary, cowardly actions that remain hidden within the favela.” Although the UPP in Santa Marta is trumpeted as the shining example of success, Vitor clarified that, “the oppression still continues, only now it is officialized.” He continued, “Even today I am disrespected, I am discriminated, I am marginalized in this place.”

Vitor Lira, a resident of Santa Marta, juxtaposed the decades of abandonment by the government with the current transformation of the community into “Disneylandia” since pacification. He argued that Santa Marta has become “a business territory,” with both real estate and tourist interests entering to exploit the favela for profit. At the peak of Santa Marta, the city has marked 150 homes for removal, citing area of risk; Vitor and others argue that it is part of an ongoing effort to increase tourism. The removal attempt highlights what Vitor referred to as the “arbitrary, cowardly actions that remain hidden within the favela.” Although the UPP in Santa Marta is trumpeted as the shining example of success, Vitor clarified that, “the oppression still continues, only now it is officialized.” He continued, “Even today I am disrespected, I am discriminated, I am marginalized in this place.”

In an emotional account, Rosilene Gonçalves, a former resident of Largo do Tanque, described how the city threw people out “as though the resident of the favela doesn’t have any value,” and tearfully explained her family’s struggle earlier this year. In the first week of February, 66 families had their homes marked for removal; three weeks later, only 10 families remained, fighting to stay in their homes or to receive adequate compensation. Rosilene—who has one son training for the Olympic volleyball team and another with special needs—described intimidation from the city if they didn’t accept the offer of only R$18,000: “They made various threats to throw us in the street if we didn’t leave,” she recalled.

Maria do Socorro, a resident of the Indiana community in Tijuca, described the community’s resistance to “the invasion of public authority” which began in early 2012. She recounted that Jorge Bittar, former Muncipal Secretary of Housing who Carlos Vainer playfully labeled “Secretary of Removals,” informed the community that they would be receiving improvements through the municipal favela upgrading program Morar Carioca and that no one would be forced to leave. Simultaneously, the Municipal Secretariat of Housing (SMH) began marking houses for removal, citing area of risk. From there, Maria recalled, the terror began: “Either you leave and accept the compensation or the bulldozer is going to tear down your house.” Again, compensation was dramatically undervalued, ranging from R$15,000 to 20,000. As the city began tearing down houses, the community started organizing: “The public authorities weren’t able to remove us from there… we have to unite the communities, to publicize the cases.” The 397 families fighting to remain are now in the process of obtaining land titles.

Emília de Souza spoke on behalf of the residents of Horto, a community of 589 families who are descendents of the workers, some over 80 years at the site, in the city’s renowned Botanical Gardens. Today, these families are being threatened with removal under the guise of “environmental protection” and have been organizing since 2008 with various government and academic institutions to develop a project for land tenure. Emília gave a fiery speech about the mafia-like relationship she perceives among various elite factions in the city in their effort to remove the community. “Unfortunately, those in power do not want the poor living in the South Zone!” she exclaimed. Not only has there been no adequate proposal for the residents’ relocation, there is also no existing proposal showing how the land will be used after: “The only proposal they have is of removing the community, but you know what for?! To hand it over to the bankers! […] but the community will resist until the end!” Applause erupted from the crowd in support of this ongoing resistance effort.

Emília de Souza spoke on behalf of the residents of Horto, a community of 589 families who are descendents of the workers, some over 80 years at the site, in the city’s renowned Botanical Gardens. Today, these families are being threatened with removal under the guise of “environmental protection” and have been organizing since 2008 with various government and academic institutions to develop a project for land tenure. Emília gave a fiery speech about the mafia-like relationship she perceives among various elite factions in the city in their effort to remove the community. “Unfortunately, those in power do not want the poor living in the South Zone!” she exclaimed. Not only has there been no adequate proposal for the residents’ relocation, there is also no existing proposal showing how the land will be used after: “The only proposal they have is of removing the community, but you know what for?! To hand it over to the bankers! […] but the community will resist until the end!” Applause erupted from the crowd in support of this ongoing resistance effort.

The event showed that the dossier is much more than a research publication. In this context of human rights violations and a systematic policy of disinformation, the dossier emerges as an extraordinary instrument for resistance. Orlando concluded with the objective of the dossier and the Popular Committee in general:

Based on the right to the city–the right of all of us to participate in the discussions and decisions related to the city where we live, this dossier invites all of us… to fight and resist against the Olympic project, marked by processes of exclusion and social inequalities… It is an invitation to mobilize around a project of the World Cup and Olympics that guarantees the respect of human rights and promotes the right to the city.”

Photos by Rafael Daguerre.