For the original article by Claudia Antunes in Portuguese published in Piauí click here (subscribers only).

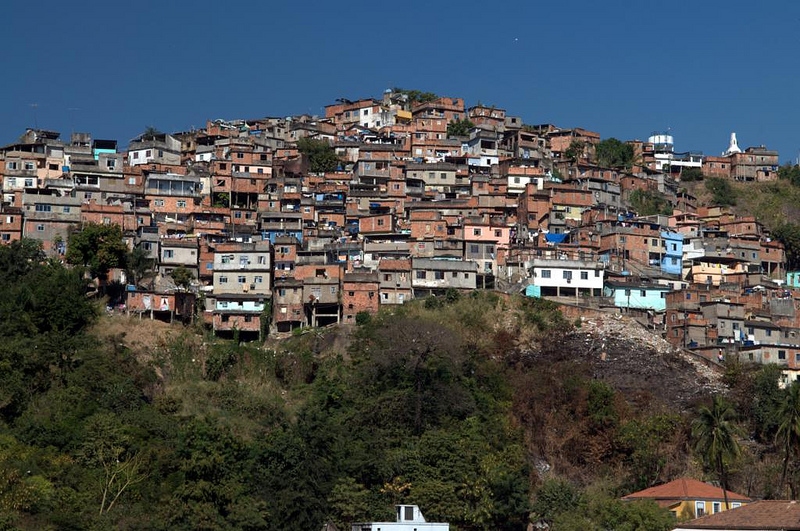

An account of the residents’ movement in Rio de Janeiro’s first favela in an era of sporting mega-events and political fragmentation.

At Cantinho dos Servidores, a restaurant and bar with blue tiled walls and bare wooden tables, you can share a generous plate of food and still expect to pay just R$6 (US$3). It’s on Sacadura Cabral Street, a road that traces the shoreline that existed little more than a century ago, until construction on the Port of Rio de Janeiro in the Guanabara Bay would permanently redraw the map. On a clear day in early September, a group of urban studies professors and students at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) met there for lunch before a research visit to the nearby favela, Providência. They were joined by two architects—recent arrivals from Denmark, a young man and woman, faces flushed by the heat.

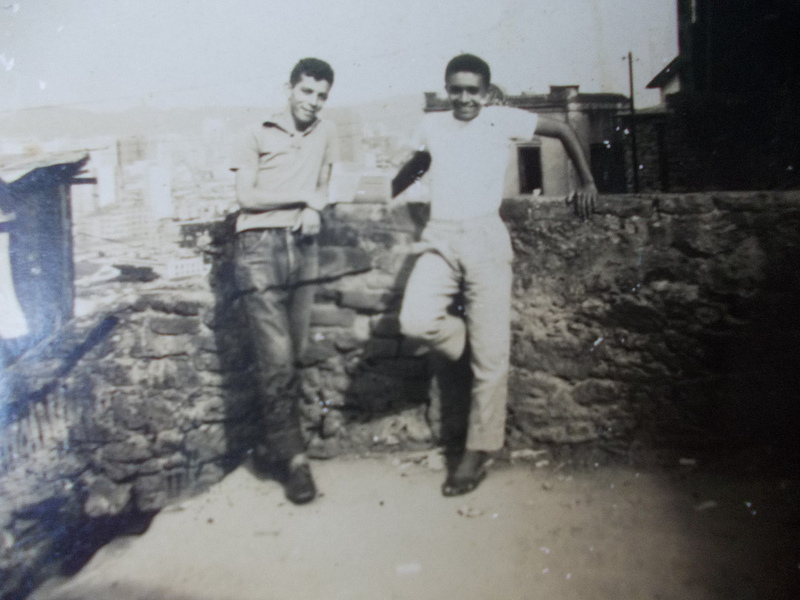

The group’s guide up the morro (hill) to Providência was photographer Mauricio Hora, professional name of Maurício da Costa Moreira Silva, the favela’s best known resident. Hora inherited his green eyes from his Portuguese grandmother and, on his mother’s side, is descended from blacks who lived in the port area for as far back as memory goes. He’s held exhibitions of his photography in the Paris subway, and some two years ago became a character in the comic book Morro da Favela, by André Diniz. His father, Luizinho, ran a boca de fumo (drug-dealing point) in Providência until his arrest and subsequent retirement in the late 70s. Before getting into photography, Hora worked as a mechanic and goldsmith.

The group’s guide up the morro (hill) to Providência was photographer Mauricio Hora, professional name of Maurício da Costa Moreira Silva, the favela’s best known resident. Hora inherited his green eyes from his Portuguese grandmother and, on his mother’s side, is descended from blacks who lived in the port area for as far back as memory goes. He’s held exhibitions of his photography in the Paris subway, and some two years ago became a character in the comic book Morro da Favela, by André Diniz. His father, Luizinho, ran a boca de fumo (drug-dealing point) in Providência until his arrest and subsequent retirement in the late 70s. Before getting into photography, Hora worked as a mechanic and goldsmith.

This wouldn’t be the first or last time the photographer would show academics and journalists around Providência. In fact, an American student in urban art, who had been following Hora’s life for 10 years unbeknownst to him, paid him a visit shortly beforehand. The alleyways of the favela, Rio’s first and historically most important, were becoming a pilgrimage route for urban planners and geographers ever since building works under the Morar Carioca (favela upgrading) program got underway. It was launched two years ago, shortly after the armed traffickers had been replaced by the Police Pacifying Unit (UPP). Researchers who make their way up the hill are generally critical of the program, which coincides with the development of the Porto Maravilha (“Marvelous Port”), the most expensive and ambitious urban project connected to the Rio 2016 Olympics.

Providência is located between the port and Central do Brasil railway station. Morar Carioca’s defining feature is an aerial cable car which will stop in the favela and connect Central do Brasil to Samba City, a fortress-like building near the pier housing the barracks of the elite Carnival samba schools. The entire route lies within the project area for the Porto Maravilha, which will redevelop three neighborhoods in Rio’s original town center – Gamboa, Santo Cristo, and Saúde – which have been left without public investment for decades.

The projects in Providência alone will cost R$164 million (US$80 million), which are to be paid for by the municipal and federal governments. Also scheduled are road widenings and the delivery of a funicular tram. This will take passengers from the cable car station to the square of the century-old Penha chapel leaving only a short walk to the Capela das Almas, an oratory at the hill’s summit, erected in 1902. The cable car will run alongside a 160-step staircase, and will connect the slopes of the formal city—where writer Machado de Assis was born—to the higher parts of the favela, where you can view Guanabara Bay, the North Zone as far as the Maracanã stadium, and all of downtown Rio.

The projects in Providência alone will cost R$164 million (US$80 million), which are to be paid for by the municipal and federal governments. Also scheduled are road widenings and the delivery of a funicular tram. This will take passengers from the cable car station to the square of the century-old Penha chapel leaving only a short walk to the Capela das Almas, an oratory at the hill’s summit, erected in 1902. The cable car will run alongside a 160-step staircase, and will connect the slopes of the formal city—where writer Machado de Assis was born—to the higher parts of the favela, where you can view Guanabara Bay, the North Zone as far as the Maracanã stadium, and all of downtown Rio.

What sparked the controversy in Providência was the announcement, in late 2010, that hundreds of families would have to leave their homes. The final number came to 671, amounting to approximately 2,000 inhabitants—more than a third of the current population of the hill and its smaller surrounding favelas, which currently stands at 4,889. The Municipal Housing Secretary (SMH) asserts that 380 of these possible removals are because of risk of landslides or unsound construction.

Unlike other communities affected by Morar Carioca, in Providência there were no consultations with the community prior to the drawing up of architectural plans. The SMH instead relied on a report produced in 2005 for Favela-Bairro, an earlier favela urbanization program. At the time, the hill was dominated by the Comando Vermelho (the “Red Command”, a major drug trafficking faction in Rio). In meetings with the municipal team, only an informal representative of the organization had even been consulted. When the council convened meetings to present its plan, there was widespread disbelief. No one wanted to understand the designs; people just wanted to know whether or not they would have to leave their homes.

The Municipal Housing Secretary says that everyone displaced will be given the opportunity to be resettled in the same area, as municipal laws stipulate. But what heightened feelings of insecurity among residents was the interval between when the houses were condemned and when the new dwellings would be completed.

The Municipal Housing Secretary says that everyone displaced will be given the opportunity to be resettled in the same area, as municipal laws stipulate. But what heightened feelings of insecurity among residents was the interval between when the houses were condemned and when the new dwellings would be completed.

According to the SMH, 752 apartments at six sites in the port area are scheduled for construction with municipal and federal money. As of December 2012, however, two plots had not yet been expropriated, and in only one of them, a site behind Central do Brasil’s rail tracks, had work actually begun. And there were almost no construction workers to be seen at the building site – an engineer reported that they had been relocated to the cable car project. Still, the city insists it will deliver 118 units at the site in the first half of this year.

At last count, 475 families in Providência had still not agreed to leave. Of the 196 who have left their homes, 135 receive municipal rent assistance, so-called “social rent”, and are waiting for their new apartments. The other 61 accepted other forms of compensation: a cash indemnity, a new home purchased with help from the city, or relocation to housing projects outside the port area through the Minha Casa, Minha Vida (My House, My Life) federal program.

Two years after construction began, the demands of those affected and the activists who support them has gone from “Stop the evictions” to “A key for a key.”

A month before he showed the morro to the group from UFRJ, Maurício Hora published an article in The New York Times. Written in conjunction with urban planner Theresa Williamson, the text was titled “In the name of the future, Rio is destroying its past.” The piece stated that families in Providência were “terrified.” It warned that the case would reopen the way for mass removals in the favelas of the city, as had happened during the twentieth century. “Rio is becoming a playground for the rich,” they concluded. Officials from the Urban Development Company of the Port Region of Rio de Janeiro (CDURP), created to manage Porto Maravilha, were uncomfortable with the tone of the article. Until then, they had had a good relationship with Hora and had supported his work to preserve the memory of the port area. “I cannot stay on the fence. I am an artist, but I’m also a resident,” he said.

Theresa Williamson, co-author of the text, is the daughter of a Brazilian mother and an English father. A young woman, with light eyes and long hair, in the last decade she completed a PhD in urban planning at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States. It was a practical dissertation, through which she created the NGO Catalytic Communities, to promote the exchange of experiences among favela residents. “I was amazed by the number of people trying to do good things, their capacity to fight to improve their lives,” said Theresa, talking in a café in Ipanema, where she lives, at the foot of another favela, Cantagalo, and gets around by bicycle.

Theresa Williamson, co-author of the text, is the daughter of a Brazilian mother and an English father. A young woman, with light eyes and long hair, in the last decade she completed a PhD in urban planning at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States. It was a practical dissertation, through which she created the NGO Catalytic Communities, to promote the exchange of experiences among favela residents. “I was amazed by the number of people trying to do good things, their capacity to fight to improve their lives,” said Theresa, talking in a café in Ipanema, where she lives, at the foot of another favela, Cantagalo, and gets around by bicycle.

In 2003, Theresa opened a venue for community leaders in Largo da Prainha, a square in the port area surrounded by colonial buildings that have recently been renovated. It was there that she met Hora. The need for a center became less evident with the spread of the Internet, so it closed its doors. Since 2011, her priority has been the bilingual RioOnWatch site. It publishes articles about the impact of the FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympics projects on popular neighborhoods and the risk of displacement for the city’s poorest populations in areas reclaimed by the city — what is called gentrification.

As Theresa anticipated, the site becAme a source for the foreign press. The New York Times asked for help on an article. The Danish architects that visited Providência at the beginning of September were drawn there by images they had seen on Al Jazeera’s English-language television channel.

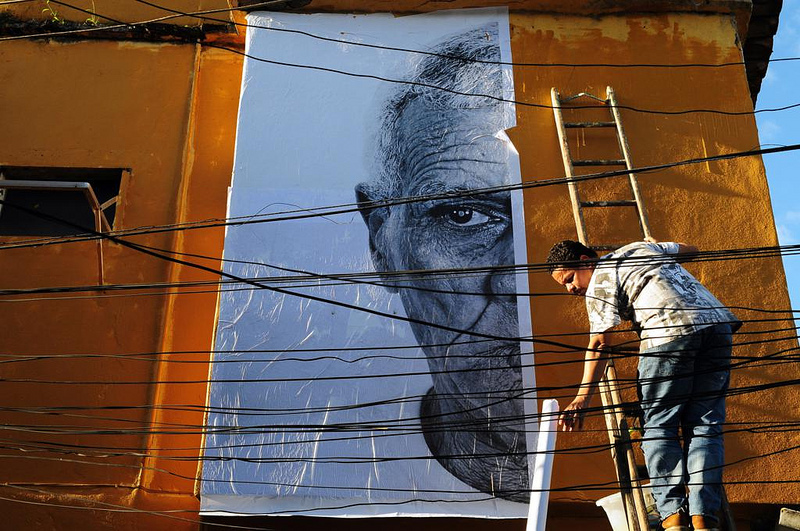

On that sunny day, Maurício Hora escorted the urban planners to Casa Amarela (the Yellow House), at the top of Providência’s staircase. The building, with a balcony on the ground floor and a rooftop deck with a view, was bought by French photographer JR to serve as a cultural center. JR, who does not divulge his full name, visited the hill in 2008. Three residents had just been murdered when soldiers occupying the favela handed them over to drug traffickers from a rival faction. At the time, the army was guarding a building site belonging to Senator Marcelo Crivella, of the PRB party, now Minister of Fishing. JR covered the walls and slopes of the favela with enormous photos of women, who he called the “heroines of the hill.”

![Children preparing photographs of residents for plastering on the side of homes marked for eviction [Photo by Maurício Hora]](https://www.rioonwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Providencia_Installation_Kids.jpg) In 2011, Hora did the same thing. He photographed 200 residents and pasted their faces on the houses earmarked for demolition. “I told them, you have to show your face so they know you exist.” The houses were marked during the day, while most residents were at work. “So you had children breaking the news to their parents. It was chaos on the hill,” he said. After that, the city agreed to move the path of the tram so that only the buildings on one side of the staircase would be torn down. Casa Amarela was among those spared.

In 2011, Hora did the same thing. He photographed 200 residents and pasted their faces on the houses earmarked for demolition. “I told them, you have to show your face so they know you exist.” The houses were marked during the day, while most residents were at work. “So you had children breaking the news to their parents. It was chaos on the hill,” he said. After that, the city agreed to move the path of the tram so that only the buildings on one side of the staircase would be torn down. Casa Amarela was among those spared.

The visitors also climbed to the summit of Providência, where Morar Carioca intends to demolish 26 houses to make way for a public square around the whitewashed oratory, which is protected as a municipal heritage site. (The story goes that it was built by veterans of the Canudos War, who settled on the hill and named the place “favela” after a scrubland plant they encountered on their campaign.)

A woman pointed out the bullet marks on the door of the oratory, from past confrontations between police and traffickers, and complained, “Now that things are better, they want to kick us out.” The urban planners criticized the hill’s transformation into a tourist site. “I think it may have potential, but the tourist who comes to a favela is going to see a favela, not a view. I don’t have anything against taking out a house to build a road, or removing someone from an area of risk, as long as those people can stay here,” said Hora.

Coming from a car equipped with a loudspeaker, the jingle for the reelection campaign of Mayor Eduardo Paes of the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party) resounded across the hill as the group headed back, at the end of the afternoon: “A lot of things have changed already / This is my Rio.” There were also officials, campaigners, and city councilors, members of the 20-party coalition created by Paes. Among them, minister Marcelo Crivella and PT’s Jorge Bittar, congressman since 1999, and Secretary of Housing most recently. Both of them were wearing light blue shirts, the Mayor’s favorite color.

Coming from a car equipped with a loudspeaker, the jingle for the reelection campaign of Mayor Eduardo Paes of the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party) resounded across the hill as the group headed back, at the end of the afternoon: “A lot of things have changed already / This is my Rio.” There were also officials, campaigners, and city councilors, members of the 20-party coalition created by Paes. Among them, minister Marcelo Crivella and PT’s Jorge Bittar, congressman since 1999, and Secretary of Housing most recently. Both of them were wearing light blue shirts, the Mayor’s favorite color.

Bittar, hair and beard neatly trimmed, became irate when questioned about the removals. “You know who I am, my life story. I’m not here to screw the poor.” The critics “have a prejudiced and ideological view of things,” he said. “The epicenter is the PSOL (Socialism and Freedom Party). They’re playing a political game by alleging that the World Cup and the Olympics are going to drive out the poor.”

A few days later, he argued in an interview that “the radical left and intellectuals” are focusing on extreme cases. “I’m not afraid of pressure; I have been on the other side. I just don’t like lies. The poorest people, who live in high-risk areas, are begging to be relocated. When a catastrophe happens, everyone blames the government for not anticipating it. When it comes to risks, we won’t settle for half-measures.”

The National Movement for Urban Reform was one of the most active movements during the redemocratization period in Brazil. Academics, neighborhood associations, and left-wing activists all influenced the 1988 Constitution, which enshrines the social function of land and the right to own small urban lots. In 2001, the City Statute regulated urban policy directives in the Constitution. In 2005, the National System for Social Interest Housing was approved, giving “priority use” of public land for affordable housing.

In a way, Rio de Janeiro was a few years ahead of the new Constitution. The favela removals were outlawed at the beginning of the 1980s following the election of Leonel Brizola to state governor. Brizola launched initiatives to urbanize these communities by engaging its residents collectively. During that period, there was a spike in community organizing. In the book Until the Last Man, published by Boitempo in April, there’s a chapter, ‘Complex of accounts,’ with interviews from community leaders that emerged during that time. Most of them were either affiliated with the PT (Labor Party) or with Brizola’s PDT (Democratic Labor Party).

In a way, Rio de Janeiro was a few years ahead of the new Constitution. The favela removals were outlawed at the beginning of the 1980s following the election of Leonel Brizola to state governor. Brizola launched initiatives to urbanize these communities by engaging its residents collectively. During that period, there was a spike in community organizing. In the book Until the Last Man, published by Boitempo in April, there’s a chapter, ‘Complex of accounts,’ with interviews from community leaders that emerged during that time. Most of them were either affiliated with the PT (Labor Party) or with Brizola’s PDT (Democratic Labor Party).

In the 1990s, drug traffickers and police militias took control of most of the favelas’ associations, and the momentum petered out. The author, Pedro Rocha de Oliveira, a philosophy professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora, pointed out more explanations for the movement’s deflation. Prime amongst them was the deindustrialization of popular neighborhoods and the “bureaucratization” of the PT. “The basic values are becoming less important for the party, and the social movement is losing its leadership. Nothing which the PSOL does now can create overnight what previously existed,” said the author, a skinny youth with a ponytail and Bermuda shorts, during an interview in the gardens of Museu da República, the former presidential palace in Catete, close to Rio’s city center.

Without any alternative housing policy, Rio’s favela population increased by more than 27% between 2000 and 2010–in the city as a whole, the population increase was 7.4%. There are 1.4 million people living in favelas, or 22% of the city’s total population.

Without any alternative housing policy, Rio’s favela population increased by more than 27% between 2000 and 2010–in the city as a whole, the population increase was 7.4%. There are 1.4 million people living in favelas, or 22% of the city’s total population.

Three years ago, after summer downpours killed 68 people in the city, mayor Eduardo Paes stated that it was “time to put an end to the political abuse of the poor and remove houses in at-risk areas.” Since then, 22,000 families have been relocated as a result of public building works or flood risk. The city authorities ordered the construction of 53,000 properties under Minha Casa, Minha Vida. An official study from 2010 showed that so far 70% of these apartments are located in the West Zone, 40 to 50 kilometres away from the city center. Hardly anyone who lives elsewhere in the city, even those in poor quality housing, wants to move there. The city government then proceeded to purchase land in better locations for the developments, instead of leaving the decision in the hands of the construction companies.

The Providência cable car station behind Central do Brasil will replace the camelódromo (street market), which caught fire in 2010. The concrete towers are already completed, but seem willfully out of place considering the surrounding poverty. On the same block are the People’s Restaurant and People’s Hotel, charging just R$1 (US$0.50) a night. The majority of its clients are people who loiter around the station. But also living on the sidewalks are drug addicts and the homeless, mixed in with the queues of passengers waiting for buses that leave from nearby garages.

The beggars eke out an existence selling cheap biscuits and used clothes. The sidewalk and road is permanently dirty and littered with scraps of cardboard, bags, bottles and plastic cups. If the plans for Porto Maravilha go to plan, the entire area will be transformed, bringing a new light rail tramline – a modern incarnation of the lines which until the 1950s were the main mode of transport in Rio.

The beggars eke out an existence selling cheap biscuits and used clothes. The sidewalk and road is permanently dirty and littered with scraps of cardboard, bags, bottles and plastic cups. If the plans for Porto Maravilha go to plan, the entire area will be transformed, bringing a new light rail tramline – a modern incarnation of the lines which until the 1950s were the main mode of transport in Rio.

At 7pm on a rainy night in mid September, Roberto Marinho crossed the area, negotiating makeshift stalls and people asleep on the pavement, as he made his way towards Pedra Lisa, the poorest part of Providência, to talk with a group of residents. He was wearing a polo shirt and carried a heavy backpack full of material from his computer science course at a private college.

Marinho is thin, serious and fairly shy. He has a thin, light brown goatee. He is married, has two children, 13 and 10 years old respectively, but looks much younger than his 37 years. On Sundays he goes to an evangelical church. He was born and raised in Providência, where his grandfather Bernardino arrived from Alagoas in 1942. He works as an assistant in the office of a construction company and lives in a house on the steps of the favela which is earmarked for demolition.

On the Facebook page Ideals of a struggle in Morro da Providência, Marinho posted his family’s story – also publicized on RioOnWatch. The plasterboard shack built by Bernardino and Aurora has since evolved into brick, concrete and reinforced steel and today stands three storeys tall. The couple had twelve children. Four of them live there now, along with seven grandchildren and three great grandchildren. Counting the wives and husbands, there are eight families altogether.

On the Facebook page Ideals of a struggle in Morro da Providência, Marinho posted his family’s story – also publicized on RioOnWatch. The plasterboard shack built by Bernardino and Aurora has since evolved into brick, concrete and reinforced steel and today stands three storeys tall. The couple had twelve children. Four of them live there now, along with seven grandchildren and three great grandchildren. Counting the wives and husbands, there are eight families altogether.

On the pathway up the hill, only Marinho’s and two other houses are still standing. He said that up till now, none of the proposals from the city government have met their needs. “What’s more, we want to play our part in the next chapter for Providência. We’ll only swap our property for one with the same specifications and in the same location. A key for a key,” he wrote.

When the removals were announced, the Providência Residents’ Association, which has existed for decades, refused to be drawn into the dispute with city authorities. So those who were about to lose their homes created a separate committee to negotiate with the authorities. This dialogue was interrupted when the Public Defenders Office launched legal proceedings, which temporarily stopped building works on the hill. Other members of the committee were giving up when Marinho joined. “Occasionally people fade away. I didn’t intend to become so involved, but it ended up feeling natural,” he said.

This breakaway committee won the support of the Port Community Forum, created in 2011, which had one foot in the universities, the other in the third sector (civil society), plus a few political connections. Even without wide institutional support, the Forum hounded the Porto Maravilha authorities. It concentrated on housing problems in the area close to the port, before the situation blew up in Providência and attention refocused on the families living there.

This breakaway committee won the support of the Port Community Forum, created in 2011, which had one foot in the universities, the other in the third sector (civil society), plus a few political connections. Even without wide institutional support, the Forum hounded the Porto Maravilha authorities. It concentrated on housing problems in the area close to the port, before the situation blew up in Providência and attention refocused on the families living there.

One of the most active coordinators in the Forum is Isabel Cristina Cardoso, Assistant Professor of Social Work at UERJ, the State University of Rio de Janeiro. Some of her students also participate, like those from the Group for Adult Education (GEP) and urbanism specialists from Fase, the oldest NGO in Brazil. They’ve been joined by two councillors from the opposition: Eliomar Coelho, formerly with the PT who has since 2008 been in the PSOL party, and Sonia Rabello from the PV (Green Party), a specialist in urban legislation.

On the Forum’s site, the activists define Porto Maravilha as part of a process of “expropriation of land and housing from the poorest elements of the population.” The youngsters from GEP offer college preparation courses and teach literacy in Providência. They’re anarchists and politically unaligned. The band Corisco, which performs at the group’s events, have a song which goes: “If there is no equality for the poor / there is no peace for the rich.”

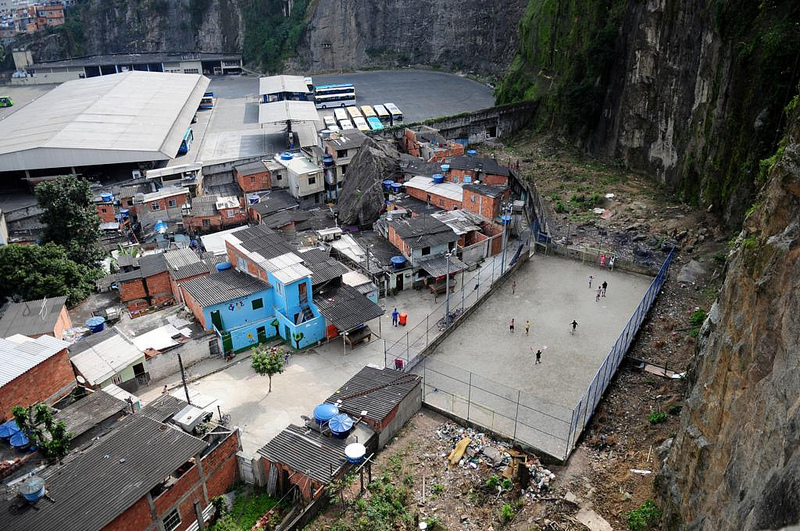

In the favelas that cover Rio’s hillsides, the poorest usually live in the highest, least accessible areas. In Providência, the reverse is true: it’s Pedra Lisa that is the outlier. Its houses are in an old quarry that was excavated at the base of the hill facing Central do Brasil station. There are 60 houses according to the official census, but it looks like more. As part of Morar Carioca, the council announced the relocation of all the families in the area, but since there are still no new houses, they’ve stayed put.

The committee meeting on that rainy September night was close to Pedra Lisa. To get there, Roberto Marinho crossed a tunnel that had been created when a boulder fell during the rains of 1969 and which still hasn’t been removed. The purpose of the meeting was to inform the community about the outcome of a court hearing a few days earlier, part of a new lawsuit filed by the public defense attorneys.

The committee meeting on that rainy September night was close to Pedra Lisa. To get there, Roberto Marinho crossed a tunnel that had been created when a boulder fell during the rains of 1969 and which still hasn’t been removed. The purpose of the meeting was to inform the community about the outcome of a court hearing a few days earlier, part of a new lawsuit filed by the public defense attorneys.

The defense demanded a stop to Morar Carioca in Providência, arguing it was a violation of the population’s rights to prior consultation – what’s known as “popular co-management,” under the City Statute. Furthermore, they said that by demolishing the houses of those who had already left, the authorities were trying to pressure remaining residents to leave too.

During the meeting, Marinho told the audience how the judge had asked the State’s opinion before making a decision. “Everyone has to be united over this, because when they begin the demolition, if someone leaves, it weakens the position for their neighbors,” he said to some seventy residents standing and listening.

Children held by their mothers were already beginning to cry in their sleep when Maria Zeneide Alves, the representative for the Pedra Lisa’s residents’ association, took to the microphone. She explained that defense attorneys would be visiting, and asked that no one make any agreements with the city beforehand. “They’re going to talk and you’re going to listen to what they have to say. They really want to get to know Pedra. Because Pedra is Pedra, isn’t that right!” she said, to the delight of the crowd. It was the first applause of the night.

Zeneide is about 40 years old, short and talkative. She used to work as a domestic cleaner, but retired early after a brain tumor operation, which leaves her plenty of free time to attend to the residents’ association. “Those of us from Pedra can’t move far away – we can only stay here in Providência, or in Santo Cristo. We just need to know exactly where it is we’re going,” she said. She recalled that before the judicial hearing, the GEP activists helped stage a “mini-march” to encourage their neighbors to attend court. “Those ladies went because they saw that I was fighting all by myself,” she said, pointing to two friends.

Zeneide is about 40 years old, short and talkative. She used to work as a domestic cleaner, but retired early after a brain tumor operation, which leaves her plenty of free time to attend to the residents’ association. “Those of us from Pedra can’t move far away – we can only stay here in Providência, or in Santo Cristo. We just need to know exactly where it is we’re going,” she said. She recalled that before the judicial hearing, the GEP activists helped stage a “mini-march” to encourage their neighbors to attend court. “Those ladies went because they saw that I was fighting all by myself,” she said, pointing to two friends.

One of them was a pale-faced, easygoing older woman. “Down at the court they thought I was crazy, but I talked till I was blue in the face,” declared Ilda Luiz Gonçalves. Originally from Paraíba, she’s lived in Pedra Lisa for 30 years. She said she doesn’t want to move because she works at Central do Brasil, where she hawks eyeglasses from 5am until 9am, which is when the authorities arrive to crack down on informal traders. Ilda was granted an official pitch to sell her goods, but said she wasn’t making any money there. “So I prefer to run from them, and make a living.” She is also afraid of having to pay for water and property taxes, should the city offer her an apartment. Today she pays just for electricity, if only to prove she owns her house.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the creation of major thoroughfares destroyed huge swathes of housing in old Rio, and isolated the port area. Then in the 1960s, the inauguration of the elevated highway (Perimetral) along the wharf sealed the area’s fate. Though it’s more than two-thirds the size of Copacabana, it has a population five times smaller, with only 28,000 inhabitants. 3.8 million of its 5 million square meters are in the historic zone. The remaining 1.2 million is land reclaimed from the sea at the turn of the twentieth century, which now holds old cargo warehouses that, in an era of standardized shipping containers, are more-or-less obsolete. In this area, most of the land belongs to the federal government.

Urban planners agree on the idea of bringing new residents to the area. Where opinion is divided is on how to allocate this public land. During President Lula’s first term, the government considered building apartments for the city’s poorest. Later, the president and the city government decided to sell the majority of the properties to finance infrastructure projects in the area. To raise more capital, the municipality increased the maximum height for new buildings on the section of reclaimed land. For the right to more vertical space, builders have to buy real estate titles, known as CEPACs (Certificate for Potential Additional Construction).

The federal government invested heavily in the project. In a 2011 auction, a fund created by its bank, Caixa Econômica Federal, bought up all the CEPACs for R$3.5 billion. This gives it priority to purchase state properties. The fund can trade titles on the market, or embark on joint ventures – for example, it is a partner with private investors in the recently announced Trump Towers Rio, a licensed brand of American billionaire Donald Trump. The fund also has a partnership with the Olympic Port complex, apartments that will house officials and journalists during the games, before being sold off as middle-class housing.

Caixa will have to pay back R$8 billion over 15 years to a public-private partnership between CDURP, the municipal company that oversees the project, and the Porto Novo Consortium, which is in charge of construction. Comprised of construction companies Odebrecht, OAS, and Carioca Engenharia, Porto Novo is responsible for delivering key services in the area (garbage collection, electric grid maintenance), policing being the main exception. Projects include modernization of the water, sewage and drainage system, improvements to streets and sidewalks, and the opening of an underground avenue to replace a part of the viaduct that will be torn down.

Caixa will have to pay back R$8 billion over 15 years to a public-private partnership between CDURP, the municipal company that oversees the project, and the Porto Novo Consortium, which is in charge of construction. Comprised of construction companies Odebrecht, OAS, and Carioca Engenharia, Porto Novo is responsible for delivering key services in the area (garbage collection, electric grid maintenance), policing being the main exception. Projects include modernization of the water, sewage and drainage system, improvements to streets and sidewalks, and the opening of an underground avenue to replace a part of the viaduct that will be torn down.

Even though Providência is located inside Porto Maravilha, and Porto Novo provides services to the favela, Morar Carioca projects are not included within its ambit. They have a separate budget and are the responsibility of a different consortium, Rio Faz, operated by the same contractors.

Last year, it was decided that Porto Novo would also build the Museum of Tomorrow, designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. The museum, shaped like a fish, will be built on a pier over the bay, in partnership with the Roberto Marinho Foundation. The latter holds more than R$88 million in contracts with the Paes administration for cultural services in the port district, including the restoration of the palace that will house the Rio Museum of Art.

Porto Maravilha has already tripled property values in the historic district – houses measuring 70 square meters, which four years ago were worth R$60,000, are now worth R$200,000. The building works have been lauded by residents of this area, especially homeowners and local businesses.

The State University of Rio de Janeiro’s (UERJ) main campus is made up of concrete buildings located next to the Maracanã stadium. Up until the 1960s, this area was home to the Esqueleto favela, which occupied the shell of a never-finished hospital building. On the afternoon of October 4th, teachers and students crowded the lobby of one of the buildings for the event “UERJ without Walls,” an exhibition of its academic output, open to the general public. Among the university projects presented in the show, one was coordinated by Professor Isabel Cardoso from the Port Community Forum. Its objective was to “support and shed light on social struggles defending the right to housing.”

Isabel has a PhD in sociology from the University of São Paulo. Her thesis examined the stimulus provided by cooperatives in Rio’s favelas as a means of easing poverty. She is an attractive woman, about 40 years old, with short brown hair, discrete glasses, almost no makeup, and manages to be didactic without talking down to her audience.

Isabel has a PhD in sociology from the University of São Paulo. Her thesis examined the stimulus provided by cooperatives in Rio’s favelas as a means of easing poverty. She is an attractive woman, about 40 years old, with short brown hair, discrete glasses, almost no makeup, and manages to be didactic without talking down to her audience.

For Isabel, the main problem with Porto Maravilha is that from the beginning, public land supposedly allocated for subsidized housing was never properly marked. It takes longer to expropriate private lots and costs more, she argues. “The residents of Providência do not want social rent. To be left without a home is simply not an option.”

I asked Isabel how she viewed the lack of political outreach within favela associations. She too believes that the drug traffickers are not the only reason. For Isabel, clientelism still persists, as attested to by the Crivella housing project. In addition, she adds, the income transfer projects, created in the ’90s, despite their positive features, turned residents into “clients” of the state. “The government will provide resources as long as you agree that it’s not a civic right, but rather the swapping of one favor for another.”

Days later, the federal government was debating the port, though this time not as an investor. A working group on housing, linked to the Human Rights Secretariat of the Presidency, convened a public hearing to discuss the impact of the construction projects related to major sporting events. The meeting was held in the auditorium of the National Institute of Technology, in the port area. There were about sixty people, including residents and activists like Isabel.

The group participants, when asked, replied that Porto Maravilha should have created a register of residents affected by the building works, and set aside funds from the Public-Private partnership for social housing. The federal working group was offended because the Municipal Housing Secretary had not sent representatives to the meeting. “If in other cities in Brazil, evictions and resettlements are accompanied by proposals, in Rio they come as faits accomplis,” said Eugênio Aragão, the working group’s coordinator and deputy attorney general of the Republic. “The authorities refuse to talk. They’ll have to prove their innocence when it comes to trial.”

The group participants, when asked, replied that Porto Maravilha should have created a register of residents affected by the building works, and set aside funds from the Public-Private partnership for social housing. The federal working group was offended because the Municipal Housing Secretary had not sent representatives to the meeting. “If in other cities in Brazil, evictions and resettlements are accompanied by proposals, in Rio they come as faits accomplis,” said Eugênio Aragão, the working group’s coordinator and deputy attorney general of the Republic. “The authorities refuse to talk. They’ll have to prove their innocence when it comes to trial.”

At the meeting, the film A Caminho da Copa (The Road to the World Cup) was shown, criticizing removals in the city. Appearing in the film was state deputy Marcelo Freixo from the PSOL party. He was Paes’ main opponent in the race for mayor and at that point had already been defeated. Paes convincingly won the two electoral zones covering the port area, though Freixo obtained almost 35% of the vote in them (against a 28% average).

The Environment Museum occupies an early twentieth century white mansion in Rio’s Botanical Gardens, in the South Zone of the city. Recently restored, it now has a modern auditorium, with colorful chairs and a big screen. It was here, at the end of October, that sociologist Alberto Gomes Silva participated in a debate about Porto Maravilha, at the invitation of geography professors at Rio’s Pontifical Catholic University (PUC).

Silva is known as a “nice guy” even by his adversaries. He is very slim, wears rimless glasses and has short, layered, straight hair. He was a member of the Movement for Urban Reform and worked for international NGO ActionAid. In December, he became president of CDURP (Urban Development Company of the Port Region of Rio de Janeiro), the municipal company that manages the port area project. At the time of the debate, he was special advisor to the CDURP and one of his assignments was to listen to the demands of dozens of interest groups around the port. These included carnival troupes as well as priestesses who look after the ruins of Cais do Valongo, the quay where ships once docked with African slaves, and which was dug up during the building works.

Silva is known as a “nice guy” even by his adversaries. He is very slim, wears rimless glasses and has short, layered, straight hair. He was a member of the Movement for Urban Reform and worked for international NGO ActionAid. In December, he became president of CDURP (Urban Development Company of the Port Region of Rio de Janeiro), the municipal company that manages the port area project. At the time of the debate, he was special advisor to the CDURP and one of his assignments was to listen to the demands of dozens of interest groups around the port. These included carnival troupes as well as priestesses who look after the ruins of Cais do Valongo, the quay where ships once docked with African slaves, and which was dug up during the building works.

Silva says there are now more experts on the port than football coaches in Brazil. “The number of theses on Porto Maravilha that have been done without listening to us is amazing. If you are going to talk about the port, we need to be heard, on ethical principle and as a methodological prerequisite. It’s valid to say that we don’t listen to the universities, but the reverse is also true,” he responded, without raising his voice, when a professor demanded he interact more with academia.

During the debate, a director of the Gamboa Hospital who was accompanying his geography student daughter, defended Silva. The hospital, which cares for the poor, has existed in the port since 1853. “Porto Maravilha has already been making inroads. There’s dialogue happening. The people in charge of the project are deeply concerned about our part of town, and are tuned in to the issues there. My employees who live in Providência are satisfied. They feel they’re being treated with care. I lived there when bullets used to fly over our heads. But the area has been pacified, the streets are quiet. We’ve come back to life,” said the doctor.

The CDURP president introduced the idea of allocating the majority of the port’s public land for working-class housing. “It’s an idealistic vision, and a misguided one. Can you imagine building a new City of God in the port district? Is that the urban vision we want? What’s more, no study has been done to see if it would be viable, or who would foot the bill. As it stands today, real estate titles are being sold for individual areas, but the whole region benefits.”

The CDURP president introduced the idea of allocating the majority of the port’s public land for working-class housing. “It’s an idealistic vision, and a misguided one. Can you imagine building a new City of God in the port district? Is that the urban vision we want? What’s more, no study has been done to see if it would be viable, or who would foot the bill. As it stands today, real estate titles are being sold for individual areas, but the whole region benefits.”

Silva believes that people are prejudiced about rising property values. “This is an old debate within the Urban Reform Movement. You have a private or public sector initiative that increases the value of your neighborhood, or makes it a better place to live – is that bad for you? How can someone who doesn’t live there decide that rising property values are bad for the people who do live there?”

He said that CDURP had allocated a prime piece of real estate near the wealthy South Zone beaches for the homeless movement, and that he’s working with the city to take stock of buildings available for the city’s poorest, promising to release a map of these locations. He mentioned new professional training initiatives, and support for businesses to help them avoid being priced out by rising property values, or having to sell their shops “to Starbucks or McDonald’s.” “Is this a legitimate debate? It is. Is it legitimate to put pressure on politicians? It is. But it’s also legitimate to do it in a way that advances things, instead of slowing them down.”

I asked Silva if the ongoing controversy is affecting the sale of CEPACs. “What actually affects things is when in meetings with investors, we assert that Providência is here to stay, that it’s being urbanized, and that it won’t be a favela anymore because the residents will own legal titles. The Central Bank is building its new headquarters over there, and I was invited to present Porto Maravilha to its employees. At the meeting, a union leader said, ‘But Providência is still going to be there – isn’t that dangerous for us?’ This wasn’t a businessman speaking; this was a union leader. Dealing with these prejudices is very difficult.”

The Deusdete bar is on Américo Brum Square, across from the future Providência cable car station. On the wall, in faded pink, are bullet marks from pre-UPP shootings, which also left a hole in the base of a statue of Saint George, on a shelf behind the bar. In the middle of a very hot day at the beginning of December, three retirees played cards at a little round table. Seated on a folding metal chair, Rosiete Marinho was drinking water from a bottle, and every now and then greeted a relative walking by – she has eighteen godchildren in the favela, with the 19th on the way.

Rosiete–no relation to Roberto Marinho, who lives by the staircase–is the president of the carnival group Coração das Meninas (Girls’ Heart) and of the League of Groups and Bands of the Port District, which is made up of twelve associations. She’s a big personality, and was one of the “heroines of the hill” photographed by French artist JR in 2008. The following year her enormous black eyes filled an entire section of wall along the River Seine, and she went to Paris for the opening of the exhibition.

Rosiete–no relation to Roberto Marinho, who lives by the staircase–is the president of the carnival group Coração das Meninas (Girls’ Heart) and of the League of Groups and Bands of the Port District, which is made up of twelve associations. She’s a big personality, and was one of the “heroines of the hill” photographed by French artist JR in 2008. The following year her enormous black eyes filled an entire section of wall along the River Seine, and she went to Paris for the opening of the exhibition.

When construction began in Providência, Rosiete’s brother’s house was marked for demolition, and she became one of the principal voices in the protest against forced evictions. She appeared in several videos, including one produced by Amnesty International. Later she left the Port Community Forum, though she denies that it was due to a failed attempt to run for city council on Marcelo Crivella’s PRB ticket.

“They said all that, and then I proved that my name wasn’t on any ballot. They also said I took money from the city. People, for the love of God! To shut my mouth? Never!” she said, over the noise of the construction site in front of us. She said she had undergone surgery for a hernia. “I suffered a setback because of my health, and then I saw the reluctance of the residents themselves who thought they had to take the money the city was offering. You get burned out. How can you go into battle and expect to win when you don’t have any soldiers?”

Rosiete called over to a thin white-haired woman who was drinking a beer at the bar. She said that the woman, Glorinha, had left the apartment where she used to live, in a building known as “Apê,” and for the last two years had been living with her two daughters and grandchildren in one room, paid for with the city’s social rent subsidy of R$400, while waiting for the apartment she had been promised by Morar Carioca. According to the Housing Secretary, Apê has structural problems and is at risk of collapse. In its place the city plans to build a gymnasium.

Rosiete called over to a thin white-haired woman who was drinking a beer at the bar. She said that the woman, Glorinha, had left the apartment where she used to live, in a building known as “Apê,” and for the last two years had been living with her two daughters and grandchildren in one room, paid for with the city’s social rent subsidy of R$400, while waiting for the apartment she had been promised by Morar Carioca. According to the Housing Secretary, Apê has structural problems and is at risk of collapse. In its place the city plans to build a gymnasium.

“It would’ve been better if Glorinha had handed over the key to her apartment and picked up the key to her new place at the same time. But they took advantage of her lack of purchasing power, of her humble position. They just threw her the R$1200 check to cover three months’ rent,” said Rosiete. Glorinha protested, saying she left because she had illegally occupied the apartment, had never paid anything, and didn’t have any document proving ownership. “Maybe she doesn’t understand,” Rosiete shot back, “but by law you owned your land since you’d lived there for more than five years.”

She said she has earned a reputation for being a troublemaker without anything to show for it. “The Residents’ Association doesn’t do much. Everybody shuts their mouths.”

The Providência Residents’ Association occupies a former crèche in the lower part of the favela, the part that faces the port, in front of Samba City. At the entrance of the two-storey building, almost entirely empty of furniture, there’s a wall with job advertisements. One December morning, the secretary was talking to two men. Distrustful, when questioned about the role of the association in reforming the morro, she retorted: “Do you know the photographer Mauricio Hora? Speak to him! He’s always in the media and says he’s the community’s leader.”

As with almost all favela associations, Providência’s acts as a registrar: it issues proof of residence and registers contracts for purchase and sale. When someone wants to throw a party, even in their own home, they go there to put in a request, as required by the UPP. The body has no affiliated members, but the minutes of the ballot show 1,025 votes were cast the 2010 elections to decide the current leadership. The president Manuel Gama is ill, so taking his place is vice-president, Maria Helena dos Santos, who everyone calls Marlene.

As with almost all favela associations, Providência’s acts as a registrar: it issues proof of residence and registers contracts for purchase and sale. When someone wants to throw a party, even in their own home, they go there to put in a request, as required by the UPP. The body has no affiliated members, but the minutes of the ballot show 1,025 votes were cast the 2010 elections to decide the current leadership. The president Manuel Gama is ill, so taking his place is vice-president, Maria Helena dos Santos, who everyone calls Marlene.

She is a short, 44 year-old lady from Paraíba with blonde highlights and delicate features. Barely out of childhood, she came to Rio to work as a cleaner, and has lived in Providência for thirty years. On this particular Friday, she turned up at the association at around midday. In her friendly manner, Marlene explained that because there are so many opinions about the building works, and not everyone agrees with the legal action taken by the defense, she prefers to remain neutral. She said she tries to act as an intermediary between the neighbors and the council representatives.

Marlene acknowledged that the situation is indeed difficult for those who will have to leave their homes or those who have already left. “The Housing Secretary is offering R$400 for rent, but you can’t find properties at this price any more. They are R$600, R$800, R$1200. The focus of the redevelopment cannot just be the cable car, but must also be housing for the residents.” Nevertheless, she was enthusiastic about what was happening. “The morro is going to be the most beautiful hill in all Rio de Janeiro. There are many elderly here, many people in wheelchairs, so the funicular tram is a godsend.”

She added that Porto Maravilha will have its own service desk inside the residents’ association. “There’s a course starting to teach women how to make flip-flops. Occasionally, internships come up on the port’s construction site and they’re always giving the residents opportunities. I just think people aren’t embracing it.”

It has been eight years since she lost her son who was involved in drug trafficking. She spoke of the episode without an angry tone. “I think he was killed by policemen. He and two other boys had committed a robbery in Bangu, West Zone, and they killed him there. When I arrived at the scene, nobody knew anything except that he had be killed.” As a single mother, she raised another son and three girls on her own. Today she runs a hair salon from home.

It has been eight years since she lost her son who was involved in drug trafficking. She spoke of the episode without an angry tone. “I think he was killed by policemen. He and two other boys had committed a robbery in Bangu, West Zone, and they killed him there. When I arrived at the scene, nobody knew anything except that he had be killed.” As a single mother, she raised another son and three girls on her own. Today she runs a hair salon from home.

Trafficking is still a delicate subject in the favela. The trade persists, albeit discreetly, and without guns on display, supplying partygoers at the increasingly popular nightclubs on Sacadura Cabral Street. Marlene doesn’t elaborate when questioned on the influence of traffickers on the association in the past. “If you’re doing social work for the community, the other side doesn’t need to be involved.”

She showed us photos of a debutante ball in Providência, promoted by the UPP for the third year running and taking place at the Museu Histórico Nacional (National Historical Museum). One of her daughters, 15 years old, with long, blonde hair, was celebrating her 15th birthday and danced the waltz with a policeman. She wore a long, pink dress paid for by the TV Globo program, Mais Você, with Ana Maria Braga, which also paid for the buffet. “Now we can say we’re raising our kids.”

On the afternoon of December 5th, the Port Community Forum got together at the Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos (New Blacks Memory and Research Institute), in Gamboa. This small single-storey building was turned into a museum and cultural center after a chance discovery in the basement, some sixteen years back, of the bones of African slaves who perished during the Transatlantic crossing and whose bodies were dumped here.

Members of the Forum were wondering how to break the news to residents that Morar Carioca works would be stopped for the second time. The decision by judge Maria Teresa Pontes Gazineu was passed down at the end of November. “The defendant shall provide a public hearing, in accordance with legal requirements, and if necessary, readjust the original project to meet the demands of those concerned,” she wrote, also insisting that the city keep the residents “informed about the timetable for leaving their properties.”

Members of the Forum were wondering how to break the news to residents that Morar Carioca works would be stopped for the second time. The decision by judge Maria Teresa Pontes Gazineu was passed down at the end of November. “The defendant shall provide a public hearing, in accordance with legal requirements, and if necessary, readjust the original project to meet the demands of those concerned,” she wrote, also insisting that the city keep the residents “informed about the timetable for leaving their properties.”

The activists celebrated the legal victory, but were also concerned. Only one person from Providência had attended the meeting, Roberto Marinho, a member of the family that lives next to the staircase, who dropped by after work. “Residents will only be mobilized by other residents. We can’t act as their guardians,” said professor Isabel Cardoso.

It was already nearly 6pm when two public defenders came running into the room. They’d discovered that the city had already been informed of the verdict, and should have stopped the machines the previous Monday, which had not happened. They were liable for a fine of R$50,000 per day, as determined by the judge, and the attorneys suggested that residents go to the police station to demand an inquiry.

Marinho, who’d only just arrived, made it clear he wasn’t prepared to do that. “They’ll soon be asking, ‘What did you go there for?’ Our fight for survival is one thing, but reporting them to the police is a different thing altogether,” he said. At the end of last year, pressure over the building works relaxed and the residents began to calm down, he explained. Besides, he joked, the fact is that now there are lots of people on the hill who want to use the cable car.

When Pierre Batista the new Municipal Housing Secretary discussed the case in his office on December 17th, the city government had already managed to cushion the cable car project from the court’s verdict, though not the more remaining construction projects taking place in Providência. Batista made his career as a civil servant at Caixa Econômica Federal and is affiliated to the PT. He replaced Jorge Bittar at the end of October in a move attributed to internal disputes within the party.

Batista is a towering figure, with blue eyes and a baritone voice. He had called three under-secretaries to accompany him to the meeting. They brought with them photos of the works and spread a large map of Providência on the table, indicating the nearby plots where the construction of new homes has been proposed. They wanted to explain the delay in this part of the project, saying that in order to determine how many units were needed, they needed to register families and see which of the compensation options they intended to take up. “Often, people want [financial] compensation, some have come from the Northeast and want to return,” explained the Secretary. In Providência, the vast majority wanted to stay.

Batista is a towering figure, with blue eyes and a baritone voice. He had called three under-secretaries to accompany him to the meeting. They brought with them photos of the works and spread a large map of Providência on the table, indicating the nearby plots where the construction of new homes has been proposed. They wanted to explain the delay in this part of the project, saying that in order to determine how many units were needed, they needed to register families and see which of the compensation options they intended to take up. “Often, people want [financial] compensation, some have come from the Northeast and want to return,” explained the Secretary. In Providência, the vast majority wanted to stay.

“The city did not go in and evict 671 families, and only then begin construction [on the replacement housing]. The number of [displaced] families is the same as the number of houses we’ll deliver,” said Batista. “Most of them will be resettled in the vicinity, in proper housing that is decent and secure.” He stated that the funding for the planned housing was already in place, and that the homes would be ready by the time the works in Providência were completed, sometime in 2014. For properties that currently house more than one family, each family will be entitled to their own apartment, according to the team. In special cases, compensation for demolished homes can reach 80% more than the R$77,000 limit, the maximum value proposed by the city for residences built on informal lots, said the Secretary.

Batista said there was no need for prior public consultation as ordered by the judge, since this was only a legal requisite in contracts exceeding R$150 million, and the original budget was just R$131 million. He did acknowledge there were no meetings in the favela before the project, and argued that in previous meetings the plans were open to changes, as had happened with the funicular tram.

Batista said there was no need for prior public consultation as ordered by the judge, since this was only a legal requisite in contracts exceeding R$150 million, and the original budget was just R$131 million. He did acknowledge there were no meetings in the favela before the project, and argued that in previous meetings the plans were open to changes, as had happened with the funicular tram.

The Secretary insisted the works are progressing “in rhythm” with the negotiations with the 475 families who have refused to leave their houses. “There’s no pressure, there’s dialogue. We are making sure everyone benefits. If we cannot reach an amicable agreement, as a last resort, we will go down the legal route,” he said. The value of compensation offered by the court is almost always less than what is offered by the city, he added, making it clear that recourse to the courts is a bad deal for the disgruntled residents of the port.

Note: Photos and captions were added in this RioOnWatch version and do not reflect content on the original Piauí article. For more images by Maurício Hora depicting the History of Providência click here.

Our deepest gratitude to Jez Smadja for compiling the final text and to Harriet Batey, Jake Cummings, Jason Yu, Katy Stone, Luana Gama, Rachel Fox and Sarah De Rose for providing translation.