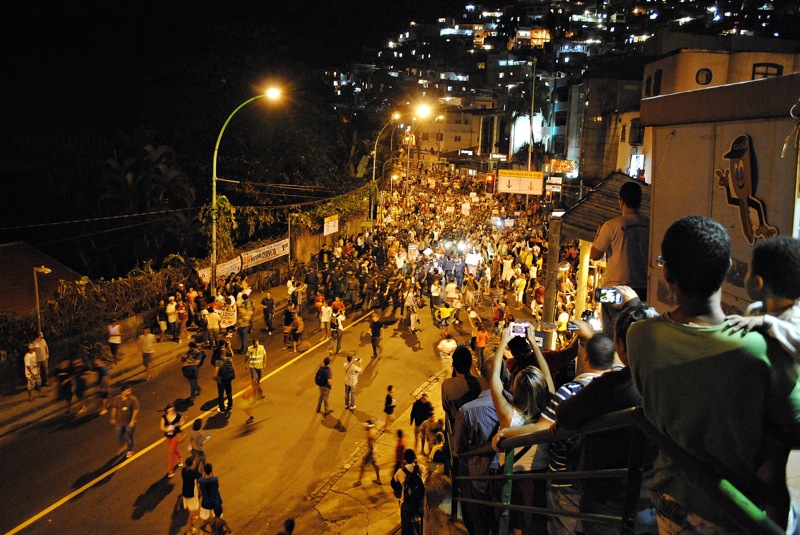

On Tuesday evening, June 25th, in a climate of ongoing demonstrations across Rio de Janeiro–where both incidents of police brutality and acts of vandalism have been widely reported–the murmur among some residents of Rio’s elite South Zone neighborhoods was that Rocinha was going to “descend on the South Zone.”

There was heavy police presence in front of the Sheraton Hotel and Governor Sérgio Cabral’s apartment in Leblon prior to the demonstration, which was organized by residents of Rocinha and Vidigal. And yet, the protest of around 2,000 people remained peaceful and festive throughout, with no incidences of vandalism or police repression. “I think it was historic!” exclaimed Leandro Lima, founder of the blog FavelaDaRocinha.com. “There hasn’t been a demonstration as calm as this one… it started well and ended even better!”

Demanding basic sanitation, health and education, demonstrators began in Rocinha, circled through São Conrado, and then snaked along Avenida Niemeyer, where the protest joined residents of Vidigal in a symbolic moment of unity between these two favelas. Leandro Lima said of this “emotional moment,” when the two communities merged into one protest, “This hasn’t happened in my lifetime, or in my parents’ lifetime.”

He explained that these neighboring communities have seen patterns of investment in one and disinvestment in the other, as well as tragic moments of violence during a war between competing drug factions. The demonstration represented the union of the two communities. Leandro says: “Rocinha and Vidigal, together for the common good, looking for improvements in both regions and taking advantage of this moment of protest.”

The energetic crowd of young and old made its way along Avenida Niemeyer to Governor Cabral’s apartment building in Leblon, holding up signs against the militarized Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) presence in the communities (“Peace without voice is fear”) and against World Cup investments in the context of failing public education (“How many schools are worth one Maracanã?”). Antonio Golgenstein, a Vidigal resident and one of the organizers of FavelArt&Foto, explained, “Today we see people going hungry in communities and so many billions being spent on the World Cup […] where are the hospitals? There isn’t even gas in the hospitals!”

The energetic crowd of young and old made its way along Avenida Niemeyer to Governor Cabral’s apartment building in Leblon, holding up signs against the militarized Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) presence in the communities (“Peace without voice is fear”) and against World Cup investments in the context of failing public education (“How many schools are worth one Maracanã?”). Antonio Golgenstein, a Vidigal resident and one of the organizers of FavelArt&Foto, explained, “Today we see people going hungry in communities and so many billions being spent on the World Cup […] where are the hospitals? There isn’t even gas in the hospitals!”

Leandro Lima explained that the demonstration was important “to show that we have the same power to change the politics here” in the favelas as the large student-oriented protests in the city center. He says, “It’s important to show that the people of Rocinha and Vidigal have the same value as a person from the asphalt [formal city] and also the same strength.”

Anderson Castro, a Vidigal resident carrying his 6-year-old son, Arthur, on his shoulders, explained that favela residents are now expressing themselves through protest, after years of fear. He said: “Some residents still don’t go to protests (because) they still have not gotten accustomed to police presence.”

In this context of unity between favelas an d empowerment through protest, one demand was articulated loud and clear: “Basic sanitation, YES! Cable car, NO!” The proposed cable car, as announced by President Dilma Rousseff a few weeks back in Rocinha, is part of the federal Growth Acceleration Project (PAC) and is set to be launched at the end of this year. As Flávio Carvalho explained, “We are here fighting for basic sanitation to be prioritized.” For residents, the cable car project prioritizes tourists’ experience over their basic needs. For Diogo Barbosa, the cable car will just make Rocinha an “exotic place” for tourists to have a beautiful aerial view of the community.

d empowerment through protest, one demand was articulated loud and clear: “Basic sanitation, YES! Cable car, NO!” The proposed cable car, as announced by President Dilma Rousseff a few weeks back in Rocinha, is part of the federal Growth Acceleration Project (PAC) and is set to be launched at the end of this year. As Flávio Carvalho explained, “We are here fighting for basic sanitation to be prioritized.” For residents, the cable car project prioritizes tourists’ experience over their basic needs. For Diogo Barbosa, the cable car will just make Rocinha an “exotic place” for tourists to have a beautiful aerial view of the community.

Residents also expressed concern given their previous experience with PAC investments in Rocinha, which prioritized highly visible works such as a Sports Complex, the Niemeyer footbridge and “make-up” (painting façades at the entrance) of the community, instead of essential public services like upgrading the sewerage system and improved garbage collection. Certain highly anticipated projects from the first phase of the PAC such as a new daycare center and popular market were left unfinished and show no signs of resuming construction.

Protesters reiterated that the exorbitant expense of the cable car could be better spent addressing high priority upgrades. The six-station cable car project is expected to cost R$600-700 million, almost half of the R$1.6 billion being invested in Rocinha under the second phase of the PAC over the next three years. Further, the PAC proposal boasts that it will build 500 new housing units in Rocinha, while failing to mention that the installations will require the removal of 2,000 families.

The example of the cable car in Complexo do Alemão illustrates the contradiction inherent in installing such a fixture in a community where the sewerage system is still open air. Additionally, many residents prefer to pay for alternate forms of transportation such as bus, van or mototaxi, rather than ride the free cable car because of the rigorous climb up dozens of steps to reach the stations. Since its inauguration in 2011, the cable car in Alemão has served 11,000 people per day (including tourists), way below its capacity of 30,000 riders.

The example of the cable car in Complexo do Alemão illustrates the contradiction inherent in installing such a fixture in a community where the sewerage system is still open air. Additionally, many residents prefer to pay for alternate forms of transportation such as bus, van or mototaxi, rather than ride the free cable car because of the rigorous climb up dozens of steps to reach the stations. Since its inauguration in 2011, the cable car in Alemão has served 11,000 people per day (including tourists), way below its capacity of 30,000 riders.

Unfortunately, the strong ties between municipal, state, and federal government politicians, and the top-down nature of the PAC mean zero participation of residents in the process. “There’s no dialogue with Rocinha about what is being done or what the community needs,” explains one resident who asked to remain anonymous. “It is very likely that [Governor] Sérgio Cabral will just go over what the people want.”

The day after the protest, Vidigal resident, photographer and longtime activist, Felipe Paiva, wrote: “The favelas descended, they made noise and left their message in a peaceful and orderly way. Whoever says that the favela resident is a mess has no idea of the beauty that was yesterday. My congratulations to the residents of Vidigal and Rocinha.”

Photos by Flavio Carvalho and Felipe Paiva