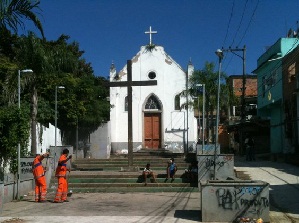

A community marked by solidarity between its residents, in Rio de Janeiro’s port area, is at risk of evictions of several of its residents. Living in this community has become a sort of family custom, meaning that parents pass their homes to their children and so on. It is a place full of character, attractions, and activities. It has almost everything! There is the traditional Brazilian Festa Junina (a party where the kids dress up as hillbillies), cruzeiro, catechism, pagode (a musical genre derived from samba), movies playing in the town square, soccer games, hide-and-seek, barbecues, and a magnificent view. The oldest favela in Rio, Morro da Providência, housed veterans of the Canudos War, ended in 1897, in the interior of Bahia.

A community marked by solidarity between its residents, in Rio de Janeiro’s port area, is at risk of evictions of several of its residents. Living in this community has become a sort of family custom, meaning that parents pass their homes to their children and so on. It is a place full of character, attractions, and activities. It has almost everything! There is the traditional Brazilian Festa Junina (a party where the kids dress up as hillbillies), cruzeiro, catechism, pagode (a musical genre derived from samba), movies playing in the town square, soccer games, hide-and-seek, barbecues, and a magnificent view. The oldest favela in Rio, Morro da Providência, housed veterans of the Canudos War, ended in 1897, in the interior of Bahia.

One of the areas most affected by these planned evictions, which are part of the Porto Maravilha project, is the stairwell, along which almost all the houses bear the stigmatizing tag of the Municipal Housing Secretary – an SMH (Secretaria Municipal de Habitação, in Portuguese) followed by a number, spray painted on houses. Those houses going up the left side of the stairs will be removed because of the appraisal that fit the whole area in an at-risk category, vulnerable to natural disasters. Those houses going up the right side of the stairs will make way for an inclined plane and cable car by mid 2013. On the day we visited the favela, photographer and community leader Maurício Hora celebrated news that those on the right side of the steps might be spared.

The long flight of stairs could serve as a fault line between different reactions from Providência residents relating to the moves: on one side, those who agree with the plan and on the other, those who don’t. Those who care, and others who don’t care very much, as long as they have somewhere to live. Ana Maria Ferrreira, stay-at-home mom and mother of six children, a resident of Providência for over 20 years, is upset about the fact that she might be separated from her loved neighbors whom she has befriended over the years. “It is a real nightmare. An inexplicable pain having to abandon the place where I grew up and have raised my children. The community relationship is so good! The families get together, have parties, and stay out late at night on the street talking without any fear of danger,” Ana says. Ana is not informed about her rights nor of the reasons for the removals, and for that reason, she doesn’t question the decisions of City Hall.

Luís Cláudio Monte, organizer of famous get-togethers in the community, was truly angered with the coldness of the SMH workers that mark homes and leave without clarifying or explaining to the residents the City’s plan of paying them a social rent stipend of R$400 during the time between eviction and the construction of a public housing unit nearby. “I will not leave here! I really won’t! I am against the bad administration of this project. The City says that we invaded this place, but we were the ones who built this place. They gave us no explanation. No one came to talk with us. They are taking what is ours,” shouted Monte, furious.

On the other hand, there are those who found solutions to their problems because of the evictions. Some residents who are unsatisfied with life within the community wait anxiously for relocation or compensation. An interesting case is that of northeasterner José Pedro dos Santos, 56, who has lived in Providência for ten years. After the death of his wife, who had pulmonary fibrosis, he didn’t return to his home in the state of Paraiba, because he didn’t have the money. “My whole life was just suffering, pain and torment. My star didn’t shine. Life is fragile, and, in this world, everything is an illusion,” he sings this song by an unknown author, which happens to tell the story of his life. Leaving his house doesn’t bother him, nor does leaving Providência. Instead of a new house, he hopes for compensation which he’ll use to move back to his land and see his children again.

The story of Maria Eliane dos Santos, 30, stay-at-home mother of three, is not much different from the previous story. She has had difficulty going up and down the steps of Providência since she was in an accident that limited the movements of her left leg, and she waits anxiously for the day she is moved to a flat place. “Also, my oldest son is risking his life here after getting involved with the drug traffickers,” she says. She wants to leave the community even if her leg lengthening surgery, scheduled soon, is successful.