This is the first article of our three-part series on the Solidarity Economy in Brazil.

When one stops to consider Rio’s hundreds of favelas for their plurality, with a lens of recognizing assets instead of just highlighting problems, one common thread is clear: in the face of public neglect, favela residents are expert at doing things for themselves, many times coming together to do so collectively. There is even a word for this, gambiarra, a native Brazilian Tupi-Guarani word meaning ‘improvised solution.’

There are many examples of this in both consumption and labor: favelas have been practicing collective consumerism since their inception (and well before the “sharing economy” was trendy); favelas come together in mutirão collective work sessions for infrastructure upgrades, such as building sewerage systems or cleaning up abandoned lots; and favelados (favela residents) have come together in work collectives, such as the baking and skills sharing collective Mangarfo featured in the short documentary, Here Is My Place.

These grassroots collective economic practices are all examples of the “solidarity economy” that exists in favelas and in other communities all over Brazil and the world. Solidarity economy has many definitions but, most broadly, is both an umbrella term and a movement that seeks to promote alternative economic structures based on collective ownership and horizontal management instead of private ownership and hierarchical management. Such structures include community banks, credit unions, family agriculture, cooperative housing, barter clubs, consumer cooperatives, and worker cooperatives or collectives, most well-known in Brazil in the industries of recycling and crafts. The goal is to decentralize wealth, root wealth in communities, and financially and politically empower stakeholders participating in these structures toward another, more just, economy.

Much of solidarity economy ascribes to the seven principles of cooperativism:

- Voluntary and free participation

- Democratic management

- Economic participation of members

- Autonomy and independence

- Education, training, and information

- Cooperation among cooperatives

- Interest in the community

Solidarity economy enterprises and protagonists

Solidarity economic enterprises, or empreendimentos econômicos solidários (EESs), are at the heart of this movement. Such initiatives typically combine individuals excluded from the labor market, or moved by the initiatives’ ideology, in the search for collective alternative means of survival.

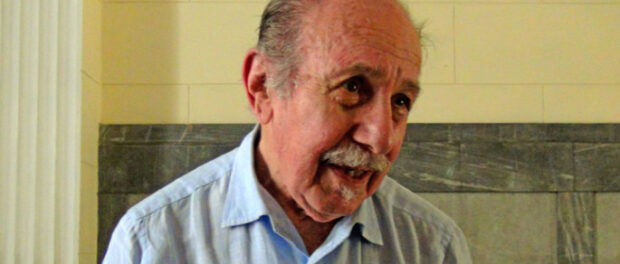

As Brazil’s former National Secretary of Solidarity Economy, Paul Singer (widely considered the father of the Brazilian solidarity economy movement), said in a public assembly in Porto Alegre last year: solidarity economy is predominantly “spread by women, young people, the unemployed—by all of the victims of capitalism.”

The solidarity economy, blending the public sector, private sector, and third (civil society and philanthropic) sector, is one manifestation of a Brazilian development model where development beneficiaries take a more active role. A 2015 UNESCO Report describes how in Rio’s favelas there is a strong presence of social organizations that are “bottom-up, without outside intervention, motivated by people who were born, grew up, and continue living in favelas.”

Indeed, a common word used to described actors in the Brazilian solidarity economy is protagonistas, or protagonists, taking leading roles in their own lives. Notably, this language is not the “self-help” language that is common amongst many “community economic development” initiatives in the US and in places like India, where initiatives that in some ways resemble solidarity economy can be observed with slightly different framing language.

Asset-based development experts Alison Mathie and Gord Cunningham frame producer cooperatives as an example of “group capacity-building,” which contrasts with “individual capacity-building.” Development projects that focus on individual capacity-building aim to improve the economic success of individuals (for example, microfinance clients), taking for granted that this will thereby lead to community economic development. However, the group capacity-building perspective sees collective action as an end in itself and development, thus, as an endogenous process. Notably, in such a framework, Mathie and Gord delineate the role of external agencies as a “facilitator of a process, and as a node in a widening network of connections the community may have with other actors.”

Solidarity economy as public policy

The solidarity economy movement has had a high degree of ostensible political success in Brazil, in part because of the wave of unemployment in the 1990s, but also because of an existing strong labor movement. Brazil created not only a national Solidarity Economy Secretariat (SENAES), but also forums and councils at the metropolitan, municipal, state, and national levels. The Brazilian Forum of Solidarity Economy (FBES), brings together state and civil society actors nationally to discuss public policy for supporting solidarity economy.

However, despite apparent policy victories, the solidarity economy political infrastructure faces many challenges nationally. First, it is still logistically difficult for EESs to formalize in Brazil. Currently, the most common forms are informal groups, associations, and cooperatives. The Brazilian cooperative law was not created with solidarity economy cooperatives in mind. The cooperative form is subject to high rates of taxation, while the association legal form is broad, serving for non-revenue generating social projects along with work collectives. There is a national campaign for a solidarity economy legal form that is based on the internal logic of cooperatives and collectives that ascribe to the solidarity economy.

While informal economy and solidarity economy are not interchangeable terms, the current state of the Brazilian solidarity economy is very informal. Of all EESs in Brazil mapped through the SIES National Mapping project finalized in 2013, 31% of EESs are informal groups, 60% are associations, and 9% cooperatives. In Rio de Janeiro state, likely due to the relatively younger solidarity economy landscape, it is even more informal, as 68% of EESs are informal groups, 25% associations, and 6% cooperatives.

However, it is important to distinguish the solidarity economy from the informal economy for a couple of key reasons. First, to be a part of the informal economy does not mean that one is practicing solidarity economics based on principles of collective benefit. Secondly, the solidarity economy movement strives for formal recognition in order to be able to take advantages of the benefits traditional businesses receive. Formal recognition does not mean fitting EESs into existing purely profit-maximizing legal forms, but creating new ones that better fit with the logic of EESs, which seek to make returns to pay workers a fair wage and reinvest in the EES and, when possible, the community.

Rio’s solidarity economy

Since January 2009, Rio’s Special Secretariat of Solidarity Economic Development (SEDES) has been the first municipal secretariat dedicated to solidarity economy in Brazil. (In other Brazilian cities solidarity economy initiatives sit under departments of work and employment.) The secretariat’s objective, according to its official page is to “formulate and execute public policy designed to widen the market and democratize access to the economy of the city. Projects of local and solidarity economy development, based in associativism and collectivism, in self-management and productive networks, are the focus of SEDES.” The SEDES website goes on to explain that “networks of small businesses, cooperatives, productive arrangements, and poles of EESs” are “vectors of an intelligent and efficient strategy of confronting and overcoming social exclusion, unemployment, and precarious work in the world’s big cities.”

A large part of SEDES’ work has been to work towards certifying Rio as the first Latin American capital to be a Fair Trade Town. Mayor Eduardo Paes committed to five related goals: create a coordinating committee of the campaign; declare support for and utilize products of fair trade in the public sector, for example by purchasing school lunches from local producers; support the placement of solidarity economy products in local markets; incentivize businesses in supporting and consuming these products, for example by utilizing uniforms made by solidarity economy entrepreneurs; and publicize the campaign in the media.

SEDES has also established goals to create two circuits of fairs in the city: Circuito Rio EcoSol, or Rio Solidarity Economy Circuit, which is a network of artisan fairs, and Circuito Carioca de Feiras Orgânicas, or Carioca Circuit of Organic Produce Fairs.

According to Ana Larronda Asti, Director of Solidarity Economy and Fair Trade at SEDES, the solidarity economy artisan fair circuit has an intentional focus on women who are residents of favelas and low-income communities. It is made up of 14 fairs around the city’s major poles, such that solidarity economy entrepreneurs have commercialization opportunities throughout each month.

Circuito Rio EcoSol locations include Complexo da Maré, Méier, and Manguinhos in the North Zone; Campo Grande, Paciência, and Santa Cruz in the West Zone; Freguesia in Jacarepaguá and Praça Saens Pena in Tijuca; Cinelândia, Praça Mauá, and São Cristóvão downtown; and Largo do Machado, Ipanema, and Leme in the South Zone.

As of June 2016, there were over 300 EESs participating. In order to participate, a group must have the legal form of association or popular cooperative, be in the business of production or commercialization, and have three or more people working for it. In addition, the group must be registered to CADSOL, the national registry for solidarity economy enterprises, and must confirm that its members have attended at least four municipal forum meetings, as well as undergone solidarity economy training from SEDES. Many of the EESs are organized into networks, facilitating collective commercialization.

Current political threats and uncertainty

Unfortunately, given the political crisis at the federal level, SEDES is in a very vulnerable position. In late May, two-thirds of the 40 person staff were let go and the R$37 million budget was cut. The Special Secretariat at the time was without a boss and “without direction, in matters both strategic and practical.”

SEDES now has a new Secretary—Franklin Dias Coelho—but the agency’s status as a Special Secretariat means it was created by an action of Mayor Eduardo Paes and not by the City Council. Its special status therefore means that it can also be disbanded by the mayor as quickly as it was established. At the national level, the Solidarity Economy Secretariat is also undergoing changes that will dramatically alter its character, including the replacement in June of Secretary Paul Singer, who was a key figure in establishing the secretariat.

Solidarity economy entrepreneurs are now organizing politically to make SEDES into an institution that is permanently part of the municipal government. This year’s turmoil leaves them vulnerable given that the majority of the solidarity economy entrepreneurs’ income is dependent on the fairs and SEDES is responsible for helping to secure the public spaces where they are held. Some of the entrepreneurs at the fairs have been fighting for two decades for supportive public policy, such as the 2012 Solidarity Economy Law which defined terms for solidarity economy and established a Municipal Council in addition to SEDES, for civil society and public sector actors to dialogue. Many of the actors in this movement fear for their livelihoods, worried that their hard-earned victories could unravel in the current political context.

With solidarity economy political infrastructure at risk, so too are the opportunities that EESs offer workers for increased quality of life and supportive spaces for women, as well as new forms of accessing rights, which will be the topics of the next two articles in the series.

Anna Cash conducted research on the solidarity economy as a platform for increasing social inclusion in 2015 in the greater Porto Alegre area, as part of a Fulbright Fellowship in partnership with the EcoSol Research Group at Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (Unisinos), and with the guidance of Professor Luiz Inácio Gaiger. She is currently a student in the Masters in City Planning program at University of California Berkeley.

Full Series: Solidarity Economy in Brazil

Part 1: Cooperative Development in Rio and Beyond

Part 2: Female Protagonists

Part 3: Expanding Citizenship in Brazilian Favelas