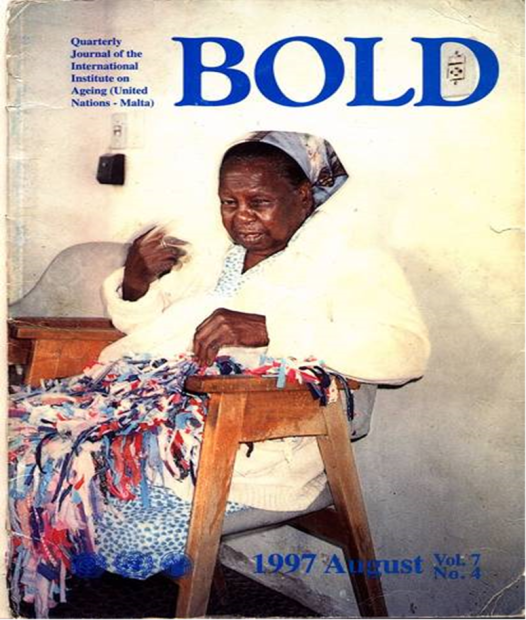

Established in 1988, initially to offer religious support to a group of 20 elderly residents of City of God, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, Casa de Santa Ana (Santa Ana’s House) became, in 1991, the first adult day care and community center for seniors within a Brazilian favela. With an innovative approach, offering workshops that promote holistic health, well-being, and preventing nursing home confinement and social isolation, the pioneering project’s main aim is to provide a safe and welcoming space for seniors from the community while their families are at work.

Daytime activities include workshops in health promotion, culture, and education. While these are primarily geared towards seniors, they are also open to children and youth from the community. This intergenerational approach seeks to foster sociability across generations, preventing the isolation so often experienced in old age.

‘Old People Belong Wherever They Want to Be’

The adult day care center at Casa de Santa Ana began with social worker Maria de Lourdes Braz, who interned at the Brigadeiro Eduardo Gomes Aeronautical Gerontological Center (CGABEG), on Ilha do Governador (Governor’s Island), between 1989 and 1991. During her training, she visited several nursing homes and witnessed the harsh reality of abandonment faced by many institutionalized seniors. It was also during this time that Braz came into contact with community and adult day care centers.

How do they work? As a preventative alternative to nursing homes, adult day care and community centers do not house seniors on a full-time or permanent basis. Instead, they provide daytime assistance to seniors and their families (in the case of adult day care centers) and offer social activities (in the case of community centers). In this way, they seek to restore seniors’ sociability and, in doing so, combat the isolation and abandonment so common in nursing home settings.

In 1991, Braz became familiar with Casa de Santa Ana, part of the Eternal Father and Saint Joseph Parish in City of God, which already supported a small group of seniors from the community. Her experience researching adult day care and community centers inspired her to propose additional support alternatives for these seniors living in socially vulnerable conditions.

With support from the church, which provided the space for the establishment of the adult day care and community center, Braz launched the social assistance initiative that continues there to this day, at Travessa Débora no. 107. Later, the property was officially transferred under a loan-for-use agreement.

Although the initial proposal prioritized seniors, over time other age groups were included, integrating all generations of the community.

Casa de Santa Ana’s first actions prioritized promoting seniors’ health: providing care such as nutrition, hygiene, wound dressings, physical therapy and exercise, emotional support, and alternative therapies (including shiatsu, acupuncture, and meditation).

Since Casa de Santa Ana’s main objectives are care, health promotion, support, and the safety of the elderly, the Family and Community Caregiver Training and Awareness Workshops soon became one of its main projects. During this period, the Casa focused on preparing family and informal caregivers of nearly all ages. Unfortunately, the project was discontinued around 2016 due to a lack of funding.

It wasn’t long before other areas such as education, the environment, and culture were included in the Casa’s range of activities, through lectures and workshops. Over time, the projects expanded to include a community family garden, agriculture, dance, percussion, and other artistic expressions. Therapeutic activities such as crochet, cooking, and reading groups also became regular features. Outings beyond the community were organized with the support of partner organizations. There was even an intergenerational choir, Voices from City of God, which received support from the Yale Alumni Chorus Foundation.

While Casa de Santa Ana remained its trade name, the initiative was formally registered in 1998 as the Santa Ana Day Center (CEDISA), obtaining its own National Registry of Legal Entities (CNPJ). From then on, it began receiving direct international support from Caritas Netherlands, while maintaining support from the Holland/Brazil Foundation and IBISS Brazil, its first Dutch partners.

Starting in the 2000s, the project expanded with a second space—Casa de Geralda, at Rua Samaritana no. 7—which became City of God’s first physical therapy center. The property was donated by Geralda Pereira da Silva, an elderly woman assisted by the project until her passing. Too small and lacking adequate infrastructure, the original building was demolished and replaced with a three-story facility. In addition to specialized physical therapy, the space hosted a variety of services, including massage therapy, treatment for chronic wounds (such as varicose ulcers), integrative therapies (acupuncture, auriculotherapy, pranic healing, meditation, shiatsu, aromatherapy, among others), group and individual psychotherapy, financial education workshops, lectures on various topics, and community discussion circles.

Casa de Geralda also served as a training site for college interns, at one point having 12 professionals continuously assisting over 150 registered seniors. Built and maintained for over two decades by editor Geraldo Jordão—founder of the publishing house Sextante—it was forced to close during the pandemic due to a lack of funding.

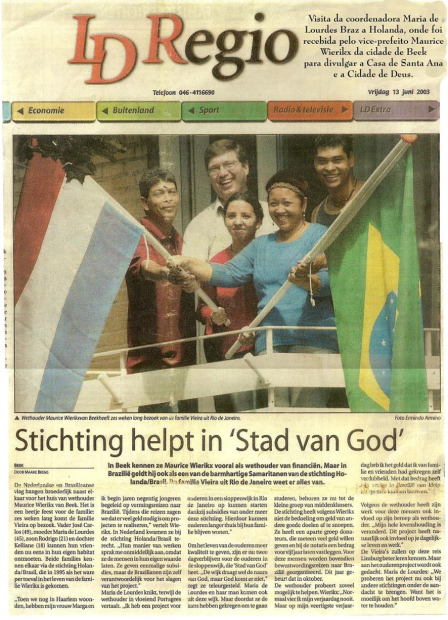

Over the years, the Casa carried out numerous mobile training courses on elderly care across Rio de Janeiro, while also presenting Casa de Santa Ana and its support model in several regions of Brazil, as well as in cities across Europe, Cuba, and the United States. These efforts earned the project local, national, and international recognition in the fight for dignity for the elderly.

Through this, Braz became a reference in the field and joined the State Council for the Defense of the Rights of the Elderly of Rio de Janeiro (CEDEPI/RJ), created in 1996 alongside many other civil society and public organizations—including Casa de Santa Ana as one of the civil society representatives, as well as a representative of City of God, the only favela with an adult day care and intergenerational community center.

The project has received both national and international recognition, including a highlight in 2002 in the Banco Real Talents of Maturity Competition; the Cultural Inclusion of the Elderly Award (through the Secretariat of Identity and Diversity of the Ministry of Culture and the Entrepreneurship Institute); the Carvalho Hosken Social Responsibility Award from the Barra Press Association (AIB)—received three times; and a tribute at the BrazilFoundation International Award in 2014, among others, along with multiple features in the media.

Throughout the years, Casa de Santa Ana has become a reference, inspiring other projects across the state of Rio.

One is the José Conrado Center for Elderly Care in the city of Volta Redonda. Another is the Christ the Redeemer Social Promotion Center in Bonsucesso, in the city of Rio’s North Zone.

“This socializing is an exchange: younger people learn from elders about aging, and often come to see it in a more positive light, while elders absorb the energy and joy of youth, remembering the good things [in their own lives] as well. At a certain age, you live a lot through memories—and if those memories are good, they sustain you.

Chronological age is the same [for everyone], there’s no way around it. But biological condition varies from person to person. People say all old people are the same. They’re not—it depends on how that [one person] has lived.

We understand that aging begins in the mother’s womb, and if you’ve had a good experience with socialization from early on, you tend to turn old age into something more positive.

Most prejudice around aging comes from this separation in social life, the idea of a ‘place for old people’ and a ‘place for young people.’ Old people belong wherever they want to be.” — Maria de Lourdes Braz

Overall, the organization has supported hundreds of seniors in City of God, along with their families and thousands of others, both directly and indirectly.

That being said, despite its long trajectory and widely recognized positive impact, even Casa de Santa Ana struggles to survive. These struggles have deepened since the pandemic, when it lost supporters.

Casa de Santa Ana’s operations depend on donations to cover essential expenses such as water, electricity, gas, internet, cleaning, hygiene, and food, as well as staff salaries—once a multidisciplinary team of 20, now reduced to just two people.

Furthermore, both physical spaces that house the organization’s projects (Casa de Geralda and Casa de Santa Ana) periodically require structural repairs and maintenance (plumbing, electrical, and painting).

The space currently assists around 25 seniors, offering virtual meditation workshops, kinesiotherapy, ballet, exercise classes, and therapeutic activities such as crafts, discussion circles, and prayer groups, among other intergenerational initiatives. All this is carried out with the support of partner organizations, including the Eternal Father Parish, the Pranatherapy Institute, Devaki, Farmanguinhos, Brazil’s national public health foundation – Fiocruz, SESI-Citizenship, the SESC Education Hub, and the Elis Regina Social Assistance Reference Center (CRAS). Meanwhile, Casa de Geralda currently opens twice a week to host activities of the Messianic Church with the community.

“I heard one [of the old ladies] say she invites her friends out to lunch, to go out on the weekend… Where else could you make these kinds of connections if not in a place like this? People say: ‘Oh, it’s just a house where old people spend the day, waiting for death to come.’ But that’s the last thing we do here. This house is full of life, of energy. They [the old ladies] have so much to give. Until last year, we even had ballet classes with 86-year-old students taking part. I’m 67, but I don’t feel my age—I feel like I still have so much to do, so much energy and vitality. I keep imagining people my age who have already given up, who have no prospects. And here we see it all in them—that they do have prospects. This is a place that offers few resources [at the moment] and presents risks [for being in a favela], but it also offers opportunities. This [Casa] is one of them. And it functions just like a home; it needs cleaning, food, maintenance—everything a home needs for [everyone’s] wellbeing. Ideally, we’d have at least R$42,000 (~US$7,750) a month to keep a small team. But, in reality, we don’t even have 10% of that. Sometimes I feel overwhelmed, because it’s a lot of responsibility. We actually had to reduce [our collaborators’] pay. And if people don’t even support the project while it’s running, if we stop [this work, it will get even worse].” — Maria de Lourdes Braz

The project is currently sustained through donations, calls for proposals, partnerships with other organizations, volunteering, sponsorships, and campaigns to cover basic needs. One of these recent initiatives was ‘Fejunina,’ a charity traditional feijoada held to raise funds for the project.

“We do what we can with the resources we manage to secure. We started publicizing the feijoada we organized two months in advance to raise money to cover another two months of salaries for our permanent staff. This creates a lot of anxiety and uncertainty, because you never know what things will be like a month from now, which makes it impossible to have continuity. We host people from Brazil and abroad, because we’re a point of reference both nationally and internationally. For a project like this to function properly, it needs continuous support. The government has to invest.” — Maria de Lourdes Braz

For Miriam Machado, 65, one of the elder women supported by the project for 15 years, the Casa’s struggle to secure support is related to prejudice against old age:

“I think they place a lot of importance on children, because they are children [with a stereotyped view that they are the future], and not on old people, because ‘they’ll die soon’ and children have something to offer. Older people don’t [anymore].” — Miriam Machado

Vanalice Magalhães, 66, who has been supported by the project for eight years, says it is very common to experience disrespect and invisibility at this stage of life:

“Last year, a doctor from the Family Health Clinic came to my house [to prescribe me some medication] and stayed only three minutes. I had to tell him I couldn’t take that medication because it was an anticoagulant, and he said: ‘How do you know that?’ I replied: ‘Because my cardiologist told me I can’t take it.’ Even so, he put it on the prescription. He never came back. It’s been three months since they took my blood and urine tests, and no one has followed up. [This lack of interest in investing in us] is because old people are expensive. A child cheers up with any silly little thing—you give them a packet of cookies and they jump with joy. But an older person is different: we know what is good and bad, and we want what we know we deserve.” — Vanalice Magalhães

‘We Are Not Preparing for a Population That Is Living Longer’

Reflecting on the stigma surrounding old age, Braz emphasizes the urgency of fostering a change in the way people think about the issue.

“Society has not yet understood that the population is aging at an accelerated pace. We are not preparing for a population that is living longer but without quality of life. There are already old people living on the streets, begging at traffic lights, needing an institution to live in because their families cannot take care of them—but [this kind of institution] does not exist. We have to think about the future [that will be old age]. I worry about when we are actually going to wake up to this, when we will truly prioritize a population that needs support. Because, whether we like it or not, people grow old and need various resources. And who takes care of this? If there are insufficient resources even for children and young people, what happens to old people? That’s exactly what I worry about: that people understand that those who don’t die young will age, and if you age without at least some basic means [of supporting yourself], then it gets much more complicated. I live in a microcosm. What we do here in City of God is a grain of sand in the universe. Imagine this multiplied? There are old people everywhere. Here, where we at least have minimal infrastructure, we already face so many challenges to keep going. Imagine in places that have nothing [for their elderly population]? Many people die without any kind of assistance. What kind of Brazil are we building for them?” — Maria de Lourdes Braz

In addition to those directly assisted, Wilson Carlos, part of the project’s permanent staff for 20 years, emphasizes the importance of supporting older people and highlights their fundamental role in society.

“These days, more value is placed [in projects] for children because they are the future. But older people are overlooked—even though they were [that too] and have so much more to teach us. A child can teach you something, but the life experience of an older person teaches much more.” — Wilson Carlos

Despite all the challenges Casa de Santa Ana currently faces, the project has transformed—and continues to transform—the lives of many older people. Machado, for example, says the Casa helped her overcome depression after the loss of her son.

“I heard a beat [coming from] there. It was percussion. I didn’t know if I could go in. Then I went to watch. That beat hit me right in the heart. I like noise. So I started taking [classes], and one day Lourdes called me over: ‘Why don’t you come spend some time with us?’ Now I do exercise classes there, I go pray the rosary, I go on outings—whenever they call me to do something, I’m there. Many children work outside the home, and older people stay alone. So some leave their parents or grandparents there, and feel more at ease knowing there are people watching over them. When one of us needs help, another takes her to the bathroom. People can work more peacefully knowing their elder is in a safe place. That is why [this work] is important. Nowadays, we don’t have as much contact with young people because the schedules and workshops changed due to a lack of funding. So we drifted away from the children. We used to be close to them, to encourage them to treat their grandparents with respect at home. But now that’s no longer happening, and it’s greatly missed.” — Miriam Machado

Magalhães, on the other hand, explains how the project helped her build new friendships and rediscover her sociability:

“The project helped with my loneliness, because I used to spend so much time by myself. [I really enjoy] the friendships—we go on outings, visit different places, meet new people. Life is not just that square [of your home, of your life]; it has to expand, you have to talk. And in these conversations, we learn from one another and start changing [understanding that there is much more beyond this]. It’s a lot of learning. Before, we would stay too much in our own bubble. [Here], our minds start to open. The world is not as small as we once imagined. I love the friendships, because when we get together with these ‘young women,’ it’s a blessing. There are those you can vent your problems to, the ones who joke around, and then you have a good laugh.” — Vanalice Magalhães

At 86, Maria José dos Santos has been taking part in the Casa’s activities for 30 years, practically since its foundation. Zezé—as she is known there—says that thanks to the project, she enjoys companionship in her daily life:

“[This is good] for distracting us. At home, I’m alone too, because the others are at work. I even have dogs [to keep me company]… but at home it’s just me, unlike here.” — Maria José dos Santos

Changing Our Relationship with Aging Starts Now

The founder of the project explains that the obstacles facing the Casa are a reflection of the neglect older people face. Even so, she emphasizes that there is hope for change. Braz shares her dream of a future where care for older people replaces the State’s neglect.

“We’ve won enough awards that this project should already have been replicated in many places. If awards came with money, we’d be rich! But in practice, that’s not how it works. There’s a lot of bureaucracy and difficulty. I’ve thought about giving up, but what I want most is to see this project prosper. We need to invest more [in a society for them]. We [as a society] don’t even have the basics [of infrastructure]. To ride a bus or get around the city, there isn’t proper accessibility for them. There aren’t enough professionals or caregivers. Many caregivers are thrown into looking after older people without knowing what they’re doing, and they end up committing violence… We have all ages within a single person. I believe there is a way forward if we teach children and young people that they will get older and [that from] a very early age they need to take care of themselves, take care of their own aging. Because if they do like us [our generation], who only started worrying about this once we were already old, it gets much harder. We need to change this culture and have more education about aging.” — Maria de Lourdes Braz

In the coming years, Braz hopes to see her project replicated and for society to finally recognize its mistake and the importance of older people to the community.

“I dream of seeing more projects like Casa de Santa Ana in other communities. They don’t have to be exactly like ours, but they should offer older people the same kind of care and support they have here. It doesn’t need [a huge structure]. It’s not difficult—it’s easy. [What is truly needed] is care, affection, and opening up new possibilities for them. [We need] to see the potential each one of them has. In spaces like this, people [as a whole] have more opportunities to evolve and to grow [even in old age].” — Maria de Lourdes Braz

To support the project financially, please donate via Centro Dia Santa Ana’s Pix (CNPJ): 03.483.529/0001-00.

The Casa receives donations both in cash and in supplies (food, hygiene, cleaning products, etc.). It also welcomes volunteers in nursing, nutrition, psychology, social work, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, physical education, and elder care. Find out how you can help through Casa de Santa Ana’s Instagram and Facebook channels, or reach out via WhatsApp +55 (21) 96928-3517.

About the author: Amanda Baroni Lopes has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca and was part of the first Journalism Laboratory organized by Maré’s community newspaper Maré de Notícias. She is the author of the Anti-Harassment Guide on Breaking, a handbook that explains what is and isn’t harassment to the Hip Hop audience and provides guidance on what to do in these situations. Lopes is from Morro do Timbau, a favela within the larger Maré favela complex.