For the original by Artur Voltolini in Portuguese for Observatório de Favelas click here.

Although 77% of Rio’s cultural facilities are concentrated in the South Zone, half of the city’s inhabitants live in the West Zone.

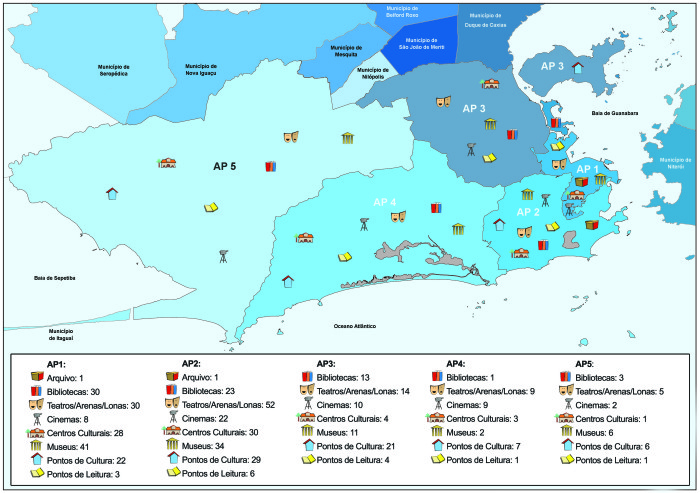

According to figures from City Hall, the city of Rio de Janeiro today has 499 cultural facilities (theaters, cinemas, libraries, museums, cultural centers, cultural points and reading points). Only 11.5% of these are in the West Zone of the city, which is currently home to nearly half of Rio’s population. The ungoverned expansion of the area, highly criticized by architects and urban planners, led a large part of the population to occupy spaces lacking adequate urban infrastructure, such as basic sanitation and transport systems.

The lack of cultural facilities in the West Zone is in itself a serious problem, yet it signals another issue: when a resident of this area wants to enjoy a cultural facility, how do they get there when 77% of these are situated in the South Zone or the Center of the city?

Rio’s transport system is orientated towards commuters traveling to and from work, which means finding a bus at night or during the weekend can be a nightmare. The Globo newspaper published an image on September 23 of huge queues of West and North Zone residents waiting for hours at the General Osório bus stop in Ipanema, to return home after a Sunday at the beach.

Following the drastic reduction of alternative forms of transport for the South Zone, nocturnal transport is now thin on the ground. Marcus Galiña, theater director, educator and member of the group Reage Artista (Artist React), said that, a few weeks ago, in the early hours of the morning as he was trying to return home to Tijuca, he waited 25 minutes at the bus stop without a single bus passing. And when one did arrive, it was not his. Marcus remembers that when he was a teenager, public transport was much more efficient.

It is not only those who live far from the South Zone who suffer the problems of urban mobility. Isabel Gomide, an experienced administrator in Rio’s theater scene, confirms that depending on the time of the show, technicians and staff also have problems getting home. “My struggle in all of the theaters I have worked in is to have the show finished by 11pm. The artists who live in the South Zone and have their own car don’t understand this problem,” says Isabel. According to her, when she was working in the SESC theater, the shows were scheduled to finish earlier, but when there was a star event or a more complicated set to dismantle, it meant finishing after 11pm. “I made the institution pay for taxis for all of the staff, security, cleaners and technicians. It cost a fortune. But that was at the SESC. Imagine in the State and Municipal theaters which just don’t have that kind of money…”

Due to these mobility issues, theaters downtown tend to start their shows at 7pm, which coincides with the end of the work day for most people in the area. Yet this complicates access for those who live further away. To arrive downtown at 7pm, for someone who lives or works in the North Zone, can take more than an hour. For this reason, cultural facilities end up serving only those who live or work close by.

Leo Bezerra, director of the Armando Gonzaga Theater in Marechal Hermes in the North Zone, says the majority of the audience who fills the theatre to watch a show come from neighboring areas, even though the region has good transport provision.

Marcus Galiña praises the creation of arenas such as Dicró in Penha, and Jovelina Pérola Negra, in Pavuna (both in the North Zone). The theater group, Teatro da Laje (Rooftop Theater), formed by residents of Vila Cruzeiro, presented a piece which brought a bigger crowd to the Dicró Arena than a show with the world famous actress, Regina Duarte, in the same arena. Galiña says that when they presented a 9pm showing of the same piece in the Maria Clara Machado Theater in the Gávea Planetarium, the actors faced great difficulties to get home. Ironically, the play they were presenting was called “The Journey from Vila Cruzeiro to Canaan of Ipanema on a Facebook page.” It narrates the saga of a group of young people from Vila Cruzeiro who face problems, which go from real-life to fantastical, simply to enjoy a strip of sand on Rio’s beaches, as they publish their adventure on their social networks.

Among the many young people from the North and West Zones who were interviewed by the Favela Observatory, urban mobility problems and difficulties in returning home were signaled as the main obstacles to consuming the culture on offer in the South Zone and downtown. Even if the event is free, travel costs are high. For the majority of those asked, the solution is to prepare themselves to combine the cultural event with a big night out in Lapa, and to catch the first buses at 5am. For the older folk, who don’t have the same energy any more, the only option is, unfortunately, a night in with a bad TV comedy.