For the original by Lívia de Cássia Godoi Moraes in Portuguese in Brasil de Fato click here.

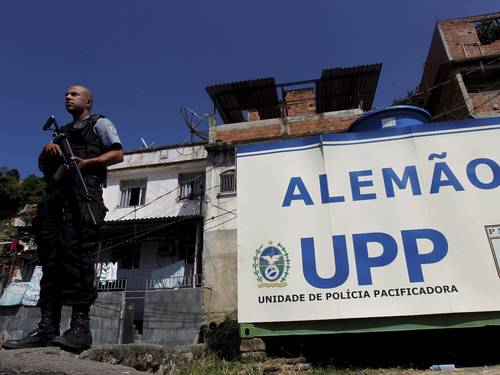

On the Rio de Janeiro state’s official website of the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs),the justification for their creation is “for security, citizenship, and social inclusion purposes.” The UPP program (which turned 5 last month) encompasses partnerships among the municipal, state, and federal governments, as well as different civil society actors, including private businesses. According to the website, “the government’s priority is the preservation of residents’ lives and liberties.”

Yet what can be observed, especially after the “disappearance” of laborer Amarildo de Souza on July 14th of this year in the Rocinha community, is the opposite of the stated objective: the climate of insecurity has grown, prompting the resurgence of the criminalization of poverty.

Yet what can be observed, especially after the “disappearance” of laborer Amarildo de Souza on July 14th of this year in the Rocinha community, is the opposite of the stated objective: the climate of insecurity has grown, prompting the resurgence of the criminalization of poverty.

Prosecutors in the “Amarildo” case concluded that 25 military police officers from the Rocinha UPP were involved in the bricklayer’s torture and death, whose body has yet to be found. According to witnesses, screams and cries for help were heard for about forty minutes coming from a container located behind the UPP base. In addition to having received electric shocks, Amarildo was drowned in a bucket and smothered with a plastic bag around his mouth and face. The blood stains on the site were removed with cooking oil.

Unfortunately, Amarildo’s disappearance is not an unusual case in the UPPs of Rio de Janeiro. As indicated in a publication by the Public Security Institute (ISP), in 18 UPPs inaugurated through 2011, there was a decrease in homicides, but an increase in resident disappearances. Before the establishment of the UPPs, there were 85 recorded disappearances. Data from 2011 now records a leap to 133.

Growing police violence in Brazil follows a crisis of legitimacy of the State, which, in the context of advancing privatizations, deregulations, and ‘financialization,’ with direct impact on public social policies, has increased the segregation and criminalization of poverty and social movements. In the name of maintaining order, the “war” against crime was implemented and reinforced through the hyperexposure of tragedies, especially on mainstream media programming.

Widespread fear and insecurity achieved the ratification of authoritarian practices inadmissible in a democratic state. The government has political and financial priorities instead. In an open letter to President Dilma Rousseff on August 14, the Citizen Debt Audit presented the following data: the general budget of the federal government, executed in 2012, was R$1.712 trillion. Of this total, 43.98% were spent on interest and debt amortization, representing almost half of the previous year’s budget. In contrast, 3.34%, 4.17%, and 22.47% were spent in education, healthcare, and social welfare, respectively. Disbursements by the Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES) in 2012 amounted to R$156 million, 12% more than the previous year, most of which was for publicly traded companies.

As we can see, the relationship between the State and the financial world has largely taken precedence over social policies.

A major piece of news appeared in the media on November 1: the president on the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP), Eduarda La Rocque, announced the launch of the UPPs Private Equity Investment Fund (FIP-UPP) set for the first half of 2014. The goal, according to La Rocque, is to organize a portfolio of social investments in both pacified and non-pacified communities in Rio and offer fund shares to Brazilian and foreign investors.

The UPPs were created as Public-Private Partnerships, with entrepreneur Eike Batista’s EBX Group as a main investor. Other investors include Coca-Cola, Bradesco Securities, Souza Cruz, Light, Metrô, and the Brazilian Football Confederation, as shown in a study conducted by Bachelor of Law, Andressa Somogy de Oliveira. However, last August, the EBX Group’s annual R$20 million agreement was broken, prompting the urgency in the creation of investment funds.

Resources under the administration of Private Equity Investment Funds (FIPs), according to the Securities Exchange Commission, are intended for the acquisition of shares, debentures, warrants, or other securities that are convertible or exchangeable for shares of publicly held or private companies participating in the decision-making process of the investee company. That is, the fund may have effective influence in the definition of strategic and management policy, with designation of members to the Board of Directors in which it participates. It is not by chance the news published in business publication Valor Econômico says those interested are well bred or successful, and businesses seeking philanthropic opportunities.

It is well known that social and environmental responsibilities are enormously relevant factors both to borrow funds from the BNDES and to maintain a companies’ share values on the stock exchanges. That is to say that it is clear the main and determining objective is, in most cases, financial and not social.

La Rocque also coordinates UPP Social, whose objective is to mobilize and articulate policies and (limited or missing) municipal services in these “pacified” territories. She affirms that ever since beginning to work for UPP Social, she receives calls from individuals and companies interested in “investing in Rio de Janeiro and in the process of integration of these communities in the context of the wider city.”

The UPPs cannot be understood as separate from the mega-events that will take place in Brazil in the next few years, especially the World Cup in 2014. The interests of the investments through FIPs in these areas derive from this same motivation. The big question remaining is: what will be the criteria of efficiency and the bait for the valuation of these investment funds in the world of speculation?

Precisely when residents of the favelas and periphery, as well as social movements, demand the demilitarization of the police, the “well bred,” successful entrepreneurs speculate over the violence, death, and massacre of the rights of this population that is already segregated and criminalized every day. It begs the question: what is the price of misery and pain on the stock market?

Lívia de Cássia Godoi Moraes is Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at UNESP/France