When asked about his experience with education growing up, Fernando–a 21 year-old from the Fumacê favela in Realengo, West Zone–said: “I’ve never liked to study. My mom forced me to go to school, but it’s something that I’ve never liked to do. In school, they don’t teach you, they just force you to do things. It’s a method for the masses.”

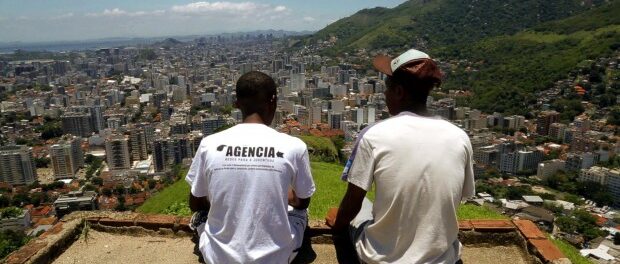

Fernando’s sentiments are echoed by thousands of children across Rio. He is one of 720 youth from 14 different favelas that have taken part in Agência de Redes para Juventude (Networks for Youth Agency) programs since 2011. Agência provides training to youth in “pacified” favelas in Rio de Janeiro, supporting youth in contesting dominant ideologies, experiencing new ways to fight for social justice, and taking positions of leadership within their communities in the face of recent developments in public security. In light of the pacification policy and changes brought about by the suppression of organized crime in their territories and the presence of the state, particularly by way of police, Agência works to improve participating young people’s view of themselves and their own communities–while addressing their position within the larger society and giving them the skills and tools for engagement. Fernando explains, “At Agência, they get to know you first before they teach you anything. They prepare you to do whatever it is that you want to do.”

The program’s model, now being exported to London and Manchester, trains selected youth in a range of practical and strategic skills and provides them with access to city-wide knowledge networks youth from such communities traditionally lack access to, over a period of three months, during which youth receive a stipend for participation. Participants are then given the chance to create, develop, present, and publicly defend their own innovative ideas with a view to transforming their lives and the communities in which they live. The whole premise is that young people need to be active participants in setting up the framework for change to take place. For them, to stimulate youth is essential for the social transformation and deepening of democracy. This philosophy is based on the teachings of its creator, Marcus Faustini, who is also a director, filmmaker and writer, advocating for a shared city, where differences come together to produce similarities, with the individual’s potential taking central stage in the reconstruction of their world.

Following training, network-building and developing and presenting their innovative ideas, 134 projects emerged from groups of participants that were selected to go through the “incubation” process, with the ideas presented to a judge’s panel. Of these, 54 were selected to receive a cash prize of R$10,000 each (US$4,540), seed funding to begin implementation. Agência will be initiating its fourth edition this May and future plans include expanding the organization’s scope to work with youth in non-“pacified” territories as well.

Here we focus on some of the impacts of Agência‘s methodology on youth participants:

Raising consciousness and a social justice-oriented community outlook

Thanks to his stint at Agência, in addition to being able to concentrate on something he is passionate about–the performing arts–as he continues his education, Fernando has been inspired to become more connected with the people living in Fumacê and to combine these two interests: “Before, I saw the favela as something forgotten. My only interest was in leaving the place as soon as possible. Now, I think differently. I think about debates to bring improvements to my community as soon as possible.”

Thanks to his stint at Agência, in addition to being able to concentrate on something he is passionate about–the performing arts–as he continues his education, Fernando has been inspired to become more connected with the people living in Fumacê and to combine these two interests: “Before, I saw the favela as something forgotten. My only interest was in leaving the place as soon as possible. Now, I think differently. I think about debates to bring improvements to my community as soon as possible.”

Fernando’s growing interest in his community and the sense that his work can help other people is reflected in the innovative idea he put forth. He proposed Mosaico, a funk/hip hop dance project in Fumacê that attempts to create a more peaceful environment and build unity among people living in different parts of the community. Prior to the installation of the UPP, there was a strong divide between two different drug factions fighting over territorial control. This conflict created an “invisible wall” inside the community and animosity among the people that lived under the two different factions. Given this situation, Fernando felt the necessity to create a project to bring people together doing what he loves most: dancing and performing.

With Mosaico, Fernando and his team create spaces and organize events to promote unity and a strong spirit of community amongst residents of different parts of the favela. Dance events and classes are held regularly at a public school (CIEP) located right on the “border” that marked the former division between the two different factions’ territories. Besides providing dance classes for youth and adults from the community, Fernando and his partners on the project have introduced dance lessons for children into the official school curriculum. Clearly proud of this achievement, Fernando said: “In our smaller class, we have about 50 children between the ages of 7 and 12 participating. The school director understood the importance of this project to bring children in the community together, and we were able to make it happen.”

Carlos Gabriel–an 18 year-old from the Batan favela in Rio’s West Zone–has also shared a transformative personal experience and increased community engagement as a result of participating: “Agência has woken me up for life. I am starting to become more politically engaged…I want to learn about politics. I want to know how politics affect my community. We need to try and understand our reality and our community apart from the opinions coming from the top. We need to understand that those opinions are biased.”

Opening a dialogue about the relationship between youth and police

When discussing the often problematic–and even chaotic–relationship between police and youth in “pacified” Rio favelas, Carlos Gabriel said, “The youth in favelas have always been repressed… we are seen as vandals, like we just want to fool around. The police don’t see us as people; they don’t see us as citizens. For them, we are all bandits. That’s the politics behind the police work in favelas.” His heartfelt comment highlights the many layers of rejection and mistrust that characterize this relationship.

When discussing the often problematic–and even chaotic–relationship between police and youth in “pacified” Rio favelas, Carlos Gabriel said, “The youth in favelas have always been repressed… we are seen as vandals, like we just want to fool around. The police don’t see us as people; they don’t see us as citizens. For them, we are all bandits. That’s the politics behind the police work in favelas.” His heartfelt comment highlights the many layers of rejection and mistrust that characterize this relationship.

Fernando deepens his analysis: “The relationship between the community and the UPP isn‘t good. Especially because I think there’s no way people coming from outside [the community] can tell us what’s best for us… They think about education for children, youth 13-15 years of age, but the ones that are 18-19, they think of them as being lost already. There are no projects directed at these young people.”

Fernando believes the state and police choose to work exclusively with children, older adults and the elderly because they feel these people can be “shaped” and it might be easier to bring them to “their side.”

Fernando believes the state and police choose to work exclusively with children, older adults and the elderly because they feel these people can be “shaped” and it might be easier to bring them to “their side.”

Carlos Gabriel points out that building a relationship with young people requires a completely different dynamic. For him, favela youth have their own way of viewing the world and won’t let anyone come in and tell them how they should live their lives. Reflecting on the “pacification” discourse about education and other social developments that have been “implemented” by organizations and the state after the police entered these territories, Carlos Gabriel said:

“We youth must show our potential. We need to show that it isn’t just because the police are here now that we, all of the sudden, want to become somebody. They need to talk to us. There are now more options for professional courses that came with the pacification, but they didn’t ask us what we wanted to do. They don’t know if I want to learn English or Spanish. They just give it to me, and if I don’t take it, they think I am just not interested in education.”

Exposing the need for an education of inquiry

The mentality that the state and educational organizations coming from the outside–and only them–have an understanding of what is best for youth has failed. In direct contrast, Agência‘s approach shows what can be accomplished when programs focus on youth’s capacity to act and are relevant because they are centered on the lived experiences and particular interests and dispositions of the youth and their families.

The mentality that the state and educational organizations coming from the outside–and only them–have an understanding of what is best for youth has failed. In direct contrast, Agência‘s approach shows what can be accomplished when programs focus on youth’s capacity to act and are relevant because they are centered on the lived experiences and particular interests and dispositions of the youth and their families.

Viviane Salles, a fiery 23 year-old from City of God and former program participant with a deep understanding of the social, political and economic interests that govern her city–calls for a new education to emerge inspired by Freirean ideologies that allow young people to exercise decision-making, while learning how to think critically and creatively about their world. She says:

“We need to think about new possibilities for people to acquire knowledge. The most important thing is to help young people think for themselves. And to do that, we need to deconstruct in order to reconstruct…. The initiatives that are most present are embedded in a mediocre model of education… they are not discussed with youth beforehand. We want to choose now. It isn’t about what you want to give me or what you think I need anymore. You have to ask me… you have to discuss things with me. You have to respect young people. Things are changing… we don’t have to just accept everything now.”

Engagement and consultation as the practice of freedom for favela youth

Favela youth have lived the reality of their territories, they have an absolute entitlement to their opinions, and they are the ones most suited to be involved in the creation and implementation of policies and programs that will have a direct impact on their communities. Understanding their backgrounds, their lived experiences as favela residents, their relationship with education, with the police and the state–as well as their hopes and dreams for the future–is fundamental for any legitimate analysis to be carried out on the “pacification” process in Rio’s favelas and its effects on youth development through education. Youth counter-stories need to be at the forefront of the “pacification” process and of any other social or security policy moving forward.

Favela youth have lived the reality of their territories, they have an absolute entitlement to their opinions, and they are the ones most suited to be involved in the creation and implementation of policies and programs that will have a direct impact on their communities. Understanding their backgrounds, their lived experiences as favela residents, their relationship with education, with the police and the state–as well as their hopes and dreams for the future–is fundamental for any legitimate analysis to be carried out on the “pacification” process in Rio’s favelas and its effects on youth development through education. Youth counter-stories need to be at the forefront of the “pacification” process and of any other social or security policy moving forward.

If the state and police continue to neglect favela youth, stigmatizing them, silencing their opinions–and attempting to make them adapt to a forced culture that isn’t embraced freely–the “pacification” process will fail. Hanier Ferrer, a 23-year old law student, activist and tutor at Agência, comments on the need for the police to open up a dialogue with impacted youth:

“The police maintain a relationship of confrontation with youth. What needs to be proved is that this youth doesn’t need–or have to be–confronted. This youth needs to be potentialized through his/her territorial culture. The idea is to break with the moralistic thinking that says what is wrong or right in relation to the behavior of favela youth or in relation to the behavior of black youth. Young people don’t want a standardized behavior… they want to have their own behavior, and show they can also circulate in other spaces.”

As Latin American education specialist Professor Carlos Torres expresses, in order for education to take place it needs to walk hand-in-hand with tolerance and respect for other people and their understanding of the world: “Construction of knowledge needs to be done in an environment of tolerance. And people need to respect different epistemologies.” This tolerance is missing from the relationship between the police and the youth in Rio’s “pacified” favelas. Hence, the further education of people through theories and practices of liberation, emancipation and transformational resistance – inserted in an environment that fosters respect and tolerance for others – is at the core of what non-formal educational programs in “pacified” territories should strive for. This is important not only for programs that cater to favela youth, but also training directed at the police force.

As Latin American education specialist Professor Carlos Torres expresses, in order for education to take place it needs to walk hand-in-hand with tolerance and respect for other people and their understanding of the world: “Construction of knowledge needs to be done in an environment of tolerance. And people need to respect different epistemologies.” This tolerance is missing from the relationship between the police and the youth in Rio’s “pacified” favelas. Hence, the further education of people through theories and practices of liberation, emancipation and transformational resistance – inserted in an environment that fosters respect and tolerance for others – is at the core of what non-formal educational programs in “pacified” territories should strive for. This is important not only for programs that cater to favela youth, but also training directed at the police force.

Right now, more than ever, youth need to take a position of leadership in their communities, contesting spaces and working to make their voices heard. Programs like Agência allow for empowerment of this sort to happen. In summary, as reflected by Fernando:

Right now, more than ever, youth need to take a position of leadership in their communities, contesting spaces and working to make their voices heard. Programs like Agência allow for empowerment of this sort to happen. In summary, as reflected by Fernando:

“Before Agência, I had nothing. I had my mom who helped me out… with food and stuff, but I didn’t have a work structure, a path… What motivates me at Agência is that it opens this path so I can keep walking. I can do things and keep discovering things… always learning.”

Statements like this from favela youth offer hope that a better and brighter future for the young people living in Rio’s favelas is not only possible, but imminent. Hence, it’s fundamental that non-formal educational initiatives that present youth as potent actors of transformation continue to be developed and implemented. As Viviane Salles says: “We have to dispute spaces and ideas. We are creating… we are experimenting with inventing a new world.”

Veriene Melo is a PhD Student and a Lemann Fellow at the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is also a Research Assistant at the Program on Poverty and Governance at Stanford University’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) where she works on a project about the pacification, UPPs and police violence in Rio de Janeiro.