This past Sunday, the Popular Committee for the World Cup and Olympics, in partnership with the National Association of Women’s Football, organized the first of four soccer events constituting this year’s People’s Cup. Four women’s teams and four men’s teams took part, representing groups negatively impacted by the approaching mega-events in Rio de Janeiro. The matches took place on a field at the top of Santa Marta, the favela famously receiving the first UPP unit in 2008 and featured in Michael Jackson’s 1995 video ‘They Don’t Care About Us’. As in the first edition in 2013, representatives of favelas from different parts of the city made up the teams.

This past Sunday, the Popular Committee for the World Cup and Olympics, in partnership with the National Association of Women’s Football, organized the first of four soccer events constituting this year’s People’s Cup. Four women’s teams and four men’s teams took part, representing groups negatively impacted by the approaching mega-events in Rio de Janeiro. The matches took place on a field at the top of Santa Marta, the favela famously receiving the first UPP unit in 2008 and featured in Michael Jackson’s 1995 video ‘They Don’t Care About Us’. As in the first edition in 2013, representatives of favelas from different parts of the city made up the teams.

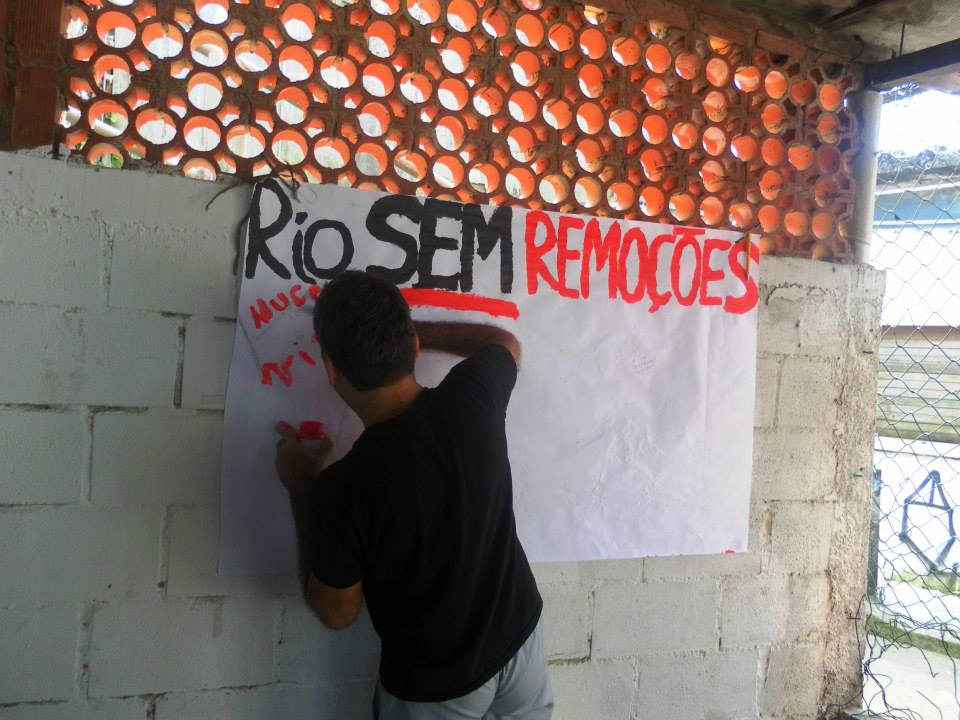

As with last year’s Evictions Cup, the People’s Cup aims to raise awareness of the ways in which Rio’s people are being impacted by mega-events’ preparations, particularly forced evictions. According to the Popular Committee, more than 100,000 people have been forced from their homes since 2009. Other impacts are highlighted this year with the participation of the National Front of Fans, who campaign against the increasing exclusivity of Brazilian football, and the United Movement of Street Vendors, representing those restricted from their work by FIFA-imposed limits on vending during the World Cup.

Despite light rain and technical issues with Santa Marta’s funicular tram, many local and international on-lookers and journalists were present from the kick-off match between the girls of Santa Cruz, West Zone, and Criciúma, North Zone. Along the pitch, teammates got louder as the game progressed and the girls from Chatuba in the Baixada Fluminense warmed up by singing and dancing. Children played on the pitch between matches; others climbed on rooftops to take in the view of Rio de Janeiro. The atmosphere was contagious; a DJ played famous funk songs, to which the women’s teams danced. Later, residents of Santa Marta played samba.

The music was interrupted by announcements reminding us of the causes that brought participants together in Santa Marta. This day of “truly popular sport” highlighted that the right to housing and work is more important than the right to speculation. This year’s event is organized in four stages, each time in a different community, to highlight that the negative impact of the World Cup is being felt citywide.

The music was interrupted by announcements reminding us of the causes that brought participants together in Santa Marta. This day of “truly popular sport” highlighted that the right to housing and work is more important than the right to speculation. This year’s event is organized in four stages, each time in a different community, to highlight that the negative impact of the World Cup is being felt citywide.

Bruna Maria, 18, and Maiara, 21, represented Chatuba and said they like living there and would leave their community for nothing. They were at the event because people are facing threats of eviction not only in central favelas like Santa Marta, but in distant ones like Chatuba as well. They cited security and education as the major challenges of their community, but health is the most important, as residents need to go to other parts of town for medical services.

Stefano Novais, 22, a chemistry student and one of the players on the National Front of Fans’ team, said soccer is “not just about what happens on the pitch, but about the impacts outside.” He said the People’s Cup is important because of the discussion of social rights during the event. Indeed, he claimed that on television the World Cup is presented as only having positive and touristic impacts, whereas in reality people are suffering, being removed for World Cup infrastructure. The National Front of Fans is present at various events protesting the World Cup; their main agenda is to guarantee popular access to Brazilian football.

Stefano Novais, 22, a chemistry student and one of the players on the National Front of Fans’ team, said soccer is “not just about what happens on the pitch, but about the impacts outside.” He said the People’s Cup is important because of the discussion of social rights during the event. Indeed, he claimed that on television the World Cup is presented as only having positive and touristic impacts, whereas in reality people are suffering, being removed for World Cup infrastructure. The National Front of Fans is present at various events protesting the World Cup; their main agenda is to guarantee popular access to Brazilian football.

João Pedro and Yuri, both 19 and Stefano’s teammates, took part in the event because of the privatization of the Maracanã stadium and access to the World Cup being closed to all but the privileged. When asked about their favorite football player, they replied Romário, who has embarked on a political career vocally denouncing the Federation of International Football Associations (FIFA). They fear the “modernization” of stadiums and thus the alienation of football fans. They claim that true fans do not want shopping malls in stadiums, but rather want to conserve traditional Brazilian football culture.

There is one change they were happy about though: girls’ participation in football in Brazil, despite the lingering preconceptions. Ingrid, 17, from Criciúma, a favela in Tijuca, was confident about her team’s chances of victory; they have been invited to more events since they won last year’s People’s Cup. Bruna Maria and Maiara from Chatuba have been playing since they were young girls and stated that the event is great for the visibility of women’s football.

There is one change they were happy about though: girls’ participation in football in Brazil, despite the lingering preconceptions. Ingrid, 17, from Criciúma, a favela in Tijuca, was confident about her team’s chances of victory; they have been invited to more events since they won last year’s People’s Cup. Bruna Maria and Maiara from Chatuba have been playing since they were young girls and stated that the event is great for the visibility of women’s football.

Marcio, 42, playing on the street vendors’ team, said the World Cup could be an opportunity for a better situation for street vendors, who are banned from selling close to stadiums during the World Cup in order to give priority to the interests of event sponsors. Jean Vitor, 18, who sells belts, enjoyed this Sunday’s event and his first time in Santa Marta. He just hopes vendors will not be pulled off the streets.

Stefano, from the National Front of Fans, is in favor of a People’s World Cup which could explore Brazilians’ passion for football in a just way, respecting human rights. The winners of Sunday’s event were Criciúma among the women’s teams and the National Front of Fans among the men’s teams. The back of the latter’s shirts read “another football is possible.” Vitor Lira, a guide and activist from Santa Marta and one of the organizers of the event, declared at the close of Sunday’s event that soccer is indeed about “integration, not segregation.”