In 2009, a new federal housing program, Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) or My Life My House, redirected resources for housing and local development in urban Brazil towards mass-construction of public housing. Just five years later, roughly two million housing units have been constructed nationwide, and the program has received both fierce criticism and high praise. As the presidential elections near, promises of expanding Minha Casa Minha Vida are pervasive, as the three leading candidates have all pledged to support expanding the program.

At its start, MCMV offered new financial mechanisms for the housing of low-income families by providing subsidies to the private construction sector, which would be responsible for design and construction of homes. Under this model, the federal government sought to achieve the dual goal of lowering the housing deficit (estimated at 7.2 million units in 2009) and stimulating the economy through the construction sector. The federal bank CAIXA was to be responsible for setting minimum requirements for design and quality of construction as well as administering the program. In its design, MCMV is very similar to other large-scale housing programs pursued in Latin American countries such as Chile or Mexico under economic reforms which sought to devolve State responsibilities to the private sector.

MCMV in Rio de Janeiro

Locally, according to CAIXA, 66,270 housing units have been contracted under the MCMV housing program in Rio de Janeiro. Of these, roughly half (33,363) are destined for families in Band 1, the lowest eligible income group, for households earning up to three minimum wages or less than R$1600 (US$713) per month. According to municipal officials, a minimum of R$75,000 (US$34,000) is spent per unit on homes built under the MCMV program, totaling at least R$5 billion (US$2.27 billion) in expenditures in Rio so far. The focus on housing construction has taken attention away from other more effective approaches to housing and urban development for the poor, such as Rio’s innovative Morar Carioca program, which promised to integrate all of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas by 2020 through both physical and social infrastructure but has now been mis-implemented and abandoned.

Based on the mere scale of the program–both in Rio and nationwide–many in government and the construction industry are eager to declare MCMV a success. While it is worth evaluating the effectiveness of the MCMV finance model and consider quantitative reductions in the housing deficit, serious qualitative concerns have been raised regarding the location and quality of such housing and the experiences of low-income families that are relocated there.

Significant Downsides

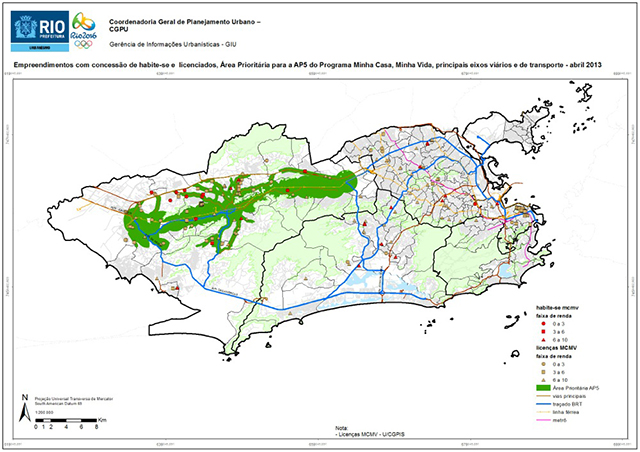

As illustrated in the official City map below, the majority of MCMV housing projects in Rio (especially those for Band 1 families) have been built in the far West Zone, oftentimes over two hours from employment opportunities and important services or amenities. The resulting geography of public housing in Rio is similar to that of other countries which have implemented this housing model. This despite Rio being known for the proximity of its favela affordable housing stock to the formal city in central areas. But now, as land acquisition and planning is left to the private construction sector, the cheapest land on the periphery is selected by default. Since the 1980s in Santiago de Chile, this lack of planning for public housing created homogeneous, isolated ghettos of poverty, even leading the government to demolish several failed housing projects under the Second Opportunities program just last year.

An isolated location has a myriad of negative effects on residents. For employment, a two to three hour commute makes it difficult, if not impossible, to access or maintain a job in one of the more centrally-located employment hubs of the city. Similarly, research by Vincente Netto shows that long distances have a negative effect on social and familial networks for very low-income families, and the social isolation typical of vertical housing especially affects the elderly. Additionally, the remote locations and absence of state services have created conditions that allowed militia groups to emerge and assert their power in several of these housing projects. In August, a large militia was uncovered in the West Zone that controlled over 1,600 MCMV housing units in the area. These militias not only create a culture of violence and fear in the housing projects, but they were also found to be charging residents illegally for water, electricity, and other basic services, putting an additional strain on already limited household budgets. Taking control even further, militias are known to impede residents’ rights to participate in the political process during and outside of election cycles.

Attention has also been drawn to the poor construction quality of MCMV apartments, with residents frequently experiencing cracking, peeling paint, faulty plumbing and flooding in their homes. In a notable case R$19 million invested in new buildings was lost when they had to be demolished due to enormous cracks. In several cases, residents have reported such problems within just a few months of moving in, which does not bode well for the durability of such units. Due to the lack of government involvement in the process, blame is often passed between CAIXA for providing insufficient oversight on the projects and the construction companies for taking shortcuts or insufficient precautions in the construction process.

A range of additional issues with the MCMV program are a result of its strict rules. Public housing residents often come from a highly flexible favela environment, where they were able to remodel their homes with the birth of a baby or the marriage of an adult child. They were accustomed to making ends meet by starting a business in rough times. In MCMV housing, none of this is allowed. Businesses are not permitted. Families are forbidden from keeping pets, extending washing on balconies (even when apartments do not have such facilities), and organizing group religious service. Oftentimes wide roads and parking are prioritized over playgrounds and leisure space. Public housing is simply not designed with an eye to maintain the qualities of favelas while addressing their deficiencies.

It is important to note that certain MCMV projects, mostly those with extra funding and support from the city government, have managed to avoid these detrimental trends of peripheral location and lack of services. Bairro Carioca project in Triagem is perhaps most representative of a transit-oriented and service-rich project, despite some of the issues listed above still applying.

Presidential Candidates Unanimous in Pledging Expansion

As the elections approach, however, even with mounting concerns with homes built under the Minha Casa Minha Vida program, which draw into question the sustainability of the program over time, funding and housing targets have continually risen since its inception. This escalation has been particularly prevalent in the current election cycle. Just weeks before the campaign period began in July, President Dilma Rousseff of the Workers Party (PT) announced Minha Casa Minha Vida 3, a new iteration of the program to be carried out through 2015. While the substantive changes of MCMV 3 relative to the current policy remains unclear, it does suggest a renewed support and enthusiasm for the program. Under MCMV 3, the nationwide housing target was raised to 3 million units by 2015.

More recently, in the immediate run-up to the elections, Rousseff announced 350,000 units are planned for the first semester of 2015, proudly claiming responsibility for the largest scale housing program in Brazil or perhaps all of Latin America. MCMV has been heavily featured in Rousseff’s campaign materials and platform, even releasing a TV commercial based on the potential of MCMV to fulfil the dream of homeownership for millions of Brazilians.

After accusations by Rousseff’s campaign that the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) candidate Marina Silva was going to eliminate the housing program, Silva has made strong statements of commitment and support for MCMV, promising to expand the program’s coverage to 4 million units. During a walk through Rocinha, the candidate said: “Our commitment is to treat communities with respect to their territory and their cultural identity. And we have a the objective of increasing the MCMV program to 4 million units, with programs to attend to communities in their own spaces of housing, urbanizing and creating living spaces; implementing full-time education, giving value to spaces of love and culture in communities.”

The Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB) candidate, senator Aécio Neves made similar promises to expand the MCMV program, despite the fact that it has been a key program of Rousseff’s Worker’s Party (PT). He has promised more focus on the lowest-income families, which the construction sector has been more reluctant to build for under the Minha Casa Minha Vida framework.

The broad support for the Minha Casa Minha Vida program across disparate political parties is unsurprising, as the program is highly politically attractive. The severe concerns raised about the long-term impacts of an investment in mass-scale low-income housing for both beneficiary families and the city at large are conveniently well beyond the scope of any politician’s cycle or even re-election aspirations, making it easier for politicians to absolve themselves of responsibility for the program over the broader horizon.

On the other hand, the immediate benefits of growth and employment in the construction sector and the discursive social benefits of providing a home to all Brazilians create quite a powerful political platform. While researchers, such as Krause, Balbum and Neto at the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) have questioned whether MCMV is truly concerned with housing or rather pure economic growth, the ability of MCMV to produce housing units for low-income families is unparalleled, creating much popular support for the program. Additionally, the leading role of the construction sector in financing political campaigns is surely influential and merits further investigation.

A Tool of Eviction

The seemingly unquestioned political support for the continuation and expansion of MCMV in the mainstream political debate is not shared by many favela residents and activists in Rio de Janeiro. Residents from dozens of communities faced with eviction to MCMV projects, due to infrastructure works for the 2016 Olympic Games, have been very vocal regarding their fears about moving and distrust of the program. In Vila Autódromo, residents have organized to save their community since the first threats of evictions in 2009. Throughout their community are signs, and at their protests banners, reading, “My House, My Life, is the one I built”–a play on the name of the housing program. In 2011 in Providência, artists and residents painted a mural showing residents resisting eviction holding a “My House My Life” poster. In these high profile cases, some families have accepted offers to move to MCMV housing, frustrated with the tense state of their communities, while others hold strong in their resistance. In many others, however, without a spotlight on their struggle or sufficient knowledge of their rights, residents succumb to municipal pressure, frequently exercised through intimidation and cooptation. For them, MCMV is a downgrade, representing a setback of potentially decades in their development.

Sara McTarnaghan is a Masters student at the University of Texas at Austin studying Community and Regional Planning and Latin American Studies. Her research is on public housing policy in Chile and Brazil.