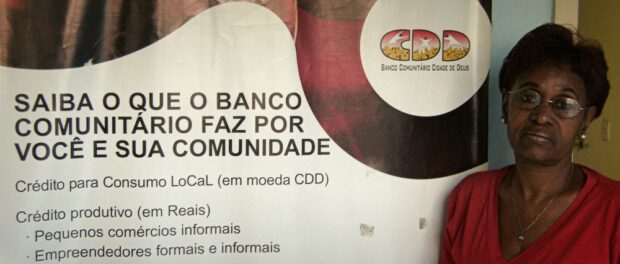

Joining a renewed global movement, City of God is the first favela in the city of Rio de Janeiro to hold its own local community currency, called the CDD after the acronym for Cidade de Deus. A recent report indicated that much of favela citizens’ income is spent outside their communities, in the formal city. The CDD is a tool to keep wealth inside the favela, while also strengthening a sense of community and shared identity.

City of God was founded in 1966 as a housing project for people forced to relocate from other favelas. While nearby Barra da Tijuca expands as the “Miami of Brazil” and future Olympics hub, with gated elite residential condominiums springing up while decades-old favelas are swiftly removed, City of God has received some public investment after the installation of a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in the community in 2009. The CDD currency idea was proposed within the context of a local development plan drafted by community residents in 2004. Inspired by the successful Banco Palmas in Ceará, North Brazil, in 2011, the City of God Community Bank started exchanging reais for CDD, coordinated by the City of Rio’s small but determined Solidarity Economics Development office.

Stimulating the local economy

“The economy usually excludes the poorest because they’re not formalized,” explains community bank intern André. “So they have difficulties in asking for loans, declaring profit, obtaining all the documentation needed… like home ownership.”

“The bank, instead, is positioned in a network of different community institutions. Accessing socially-tied knowledge–coming from churches, schools and other community activities–to issue the loans, without the need of heavy restrictions or guarantors,” he adds. “[The community bank and solidarity economics] don’t treat people like they are anonymous, getting to know them [instead], trying to establish a closer relationship.”

The social currency is also a response to identity, stigma and social status issues. The CDD, by strengthening local identity, membership and belonging in the favela, can be a catalyst for local development. “What if entrepreneurs start scouting, recruiting or training in the favela?” asked founder and coordinator of community-based organization Alfazendo, Iara Oliveira.“There won’t be development if all our resources are transferred outside the favela.”

Re-engaging the community via communication

After three years of activity in which the bank has survived various difficulties and a robbery, now the bank is undergoing restructuring efforts. The robbery incident slowed down the flow of exchanged currency (from around 1000-2000 CDD per month, in 2012, to 100-200 CDD, this year), but despite adversity the bank survived. They launched the bank’s first contest on September 15, calling for creative works to tell the story of the bank and currency through the notable personalities featured on the banknotes.

“It happened back-to-front. The bank was created before the culture and discourses were,” explained Iara, who has come to understand the program’s early limitations. “The money time is not the time of people’s culture and identities.”

Communication is the key: bringing the currency to schools, explaining the significance of the people chosen to feature on the banknotes–people from the community who are involved in social projects and fight for the favela’s development.

The bank is now re-engaging its partners and implementing strategies that worked well for Banco Palmas, re-building them to fit the peculiarities of their favela. This in contrast with social policies that come from outside the community and fail to engage with present activities, which creates conflicts and inefficiencies. In this regard, the social currency provides a vehicle for sustainable development, framing issues in an environment of all-connected members of the community, relying on local knowledge and services, social movements and political discussions of the favela itself.

It is also a tool of empowerment. As Iara explained: “Social currency is more than business, it’s power: the one who holds money and communication, has power.”

City of God isn’t the only community in Greater Rio with a social currency: Saracuruna in Duque de Caxias and Preventório in Niterói founded community banks in partnership with the Solidarity Economics Entrepreneurs Incubator at the Fluminense Federal University (IEES-UFF). Residents of Complexo do Alemão have also been considering the possibility of a local currency through the City program launched in City of God.

CDD users’ criticisms and hopes

Many residents value the currency greatly and look forward to its returning to increased circulation. Maria Cristina Neves Costa, 59, favela resident and coordinator of the community bank said: “I used to shop at the Rainha [supermarket] with CDD. I miss it a lot. Right now they’re not accepting it anymore, the CDD slowed down and they also stopped it.”

She explained how CDD can give more financial security to residents: “When people don’t have reais anymore, at least they can spend their CDD–or ask for a loan in CDD–inside the community.”

Other residents complain about the lack of adequate promotion of the CDD. Wanderlucia Farias, 45, originally from Paraíba, moved to City of God six years ago and has owned a jewelry business for four years.

“I got to know the CDD at the meetings organized by the City of God Inova Commerical Polo [a merchant association sponsored by Rio de Janeiro’s local government, established two years ago for the first time in a favela] in Cidade de Deus. Almost all the different merchants accepted it, registered and feature it in their businesses. Yet, this money didn’t gain that much ground, it’s not circulating enough. It’s a good project for the community, but it lacks promotion that spreads its full comprehension and importance.”

Sandra Mara, 54, lives outside City of God but works in a clothes shop in the community. She also feels the project should look to expand and market its benefits to a larger community audience. “We are asking the bank to engage in fostering the CDD. For right now the exchange of currency is slow,” she explained. “It would be good for the development of the whole community to give incentives to the economy and people of City of God.”

Sergio Luigi Ribas, 51, former favela resident and owner of an ice-cream shop, contextualized the CDD phenomenon.

“When it started, there was a big movement from the media, showing the novelty of this currency and its use in Rio de Janeiro,” Sergio recalled. “As the parties and celebration faded, residents lost interest.”

Sergio believes in the importance of CDD beyond its economic advantages: “Young people are important in this process of marketing. They are multipliers [of change],” he said, referring to the bank’s contest and school talks. “Many people came visiting and researching, from China, Norway, Italy. It would be nice to show off the name of ‘City of God’ not through violence and problems, but innovation and solutions.”