A report on the index of teenage homicides released on Wednesday, January 28 revealed that 42,000 teenagers might be victims of homicide by 2019 if the Brazilian government does not take action. The study entitled ‘Homicides in Adolescence in Brazil’ was launched in hotel Windsor Guanabara in Centro, along with an interministerial program to decrease the number of homicides among the young population.

The report was presented by the Federal Human Rights Secretariat, UNICEF, Observatório de Favelas and the State University of Rio’s Violence Laboratory with the objective of “systemic monitoring of homicide numbers among the young population, so as to contribute to policies to combat violence.” It covered data from the period 2005-2012.

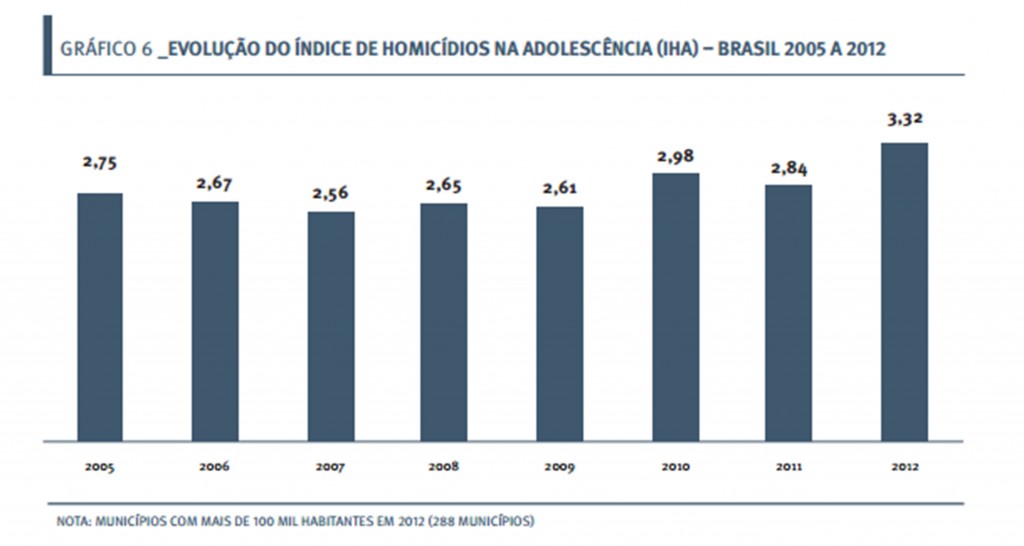

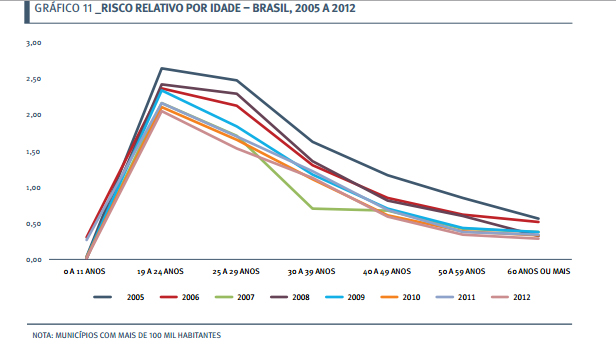

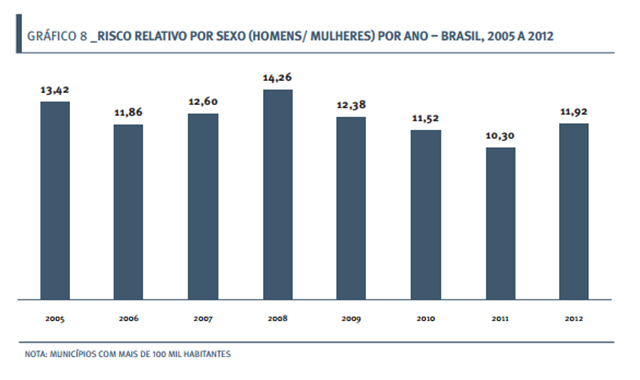

The yearly number of homicides in the general population has remained stable throughout this period while that of teen homicides remained high but then rose even more–by 17%–between 2011 and 2012, with firearms identified as the main weapon used. The study also revealed that most vulnerable young people are black males between the ages of 19 and 24. Black young people are 2.96 more likely to be victims of fatal violence than their white counterparts, and men are 11.92 times more likely to be homicide victims than women.

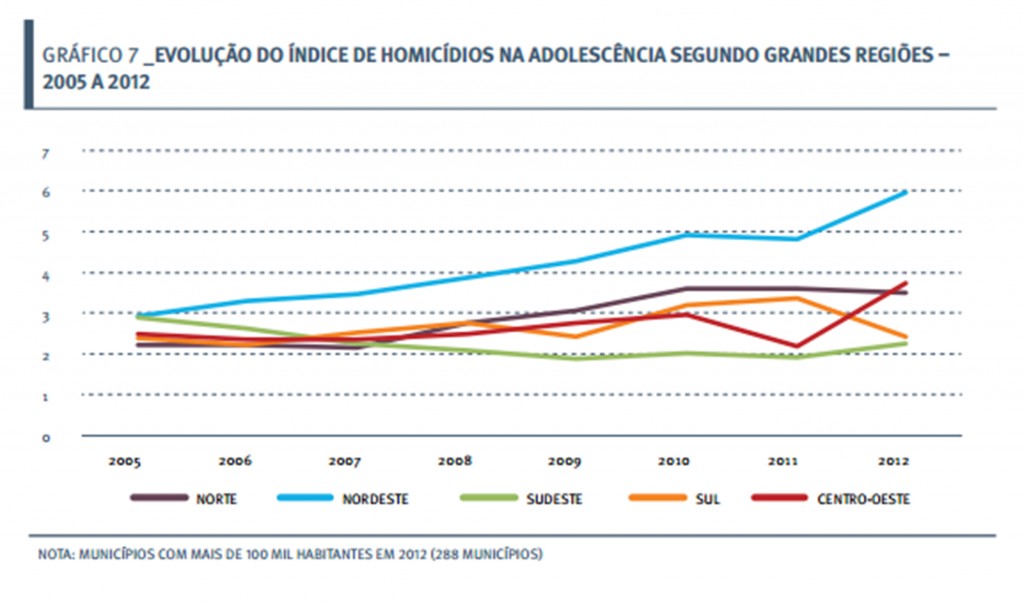

While violence against young people saw a slight decrease in the south, southeast and center of Brazil, a worrying rise was seen in the north and northeast of the country. The most dangerous state for young people was identified as Alagoas, followed by Bahia and Ceará. Rio de Janeiro is the 17th most dangerous in a list of 27. Coordinator of the study Ignacio Cano detected a correlation between the rise in violence and fast economic development, a trend that was seen specifically in the northeast.

In addition to the launching of the report, at the event the federal government announced a pact between local, state and federal governments to eradicate fatal violence of young people. Minister for Human Rights Ideli Salvatti and Minister for Racial Equality Nilma Lino Gomeswere presented the Plan for Combating Fatal Violence Against Children and Adolescents which will be “an act of the federal government to prevent the deaths of teenagers and end this cycle of violence.”

Salvatti explained: “We will intensify the partnerships with all entities of federal and civil society, besides working in an interministerial way.” She also said she hoped the study would “create a national uproar of indignation” that would encourage action from civil society.

Observatório de Favelas coordinator Jorge Barbosa, who contributed to the research, said the results of the report were “unacceptable” and that society had to have an “agenda for the appreciation of life.” He echoed Salvatti in saying civil society has a major part to play in the eradication of violence.

He said: “We need to get over this culture of intolerance and negligence in society. Civil society needs to be an active subject in this fight. We need to build an agenda where the government and civil society can work together. We need to stop defining young people as citizens of the future and start defining them as citizens of the present.”

Barbosa also described concrete ways for citizens to get involved in the eradication of violence, including participating directly in proposing and creating policy.

“Civil society has to be intentional with regard to this, making proposals, not just denouncing abuses,” he said. “Proposals like arms control, proposals against questionably justified homicides by the police, proposals against the reduction of the age at which youth can be incarcerated as adults. Most importantly, civil society has to build spaces of coexistence, spaces of creativity, spaces for encounters, where young people and adults can meet on another level–of recognizing their differences, of coexistence. We have to change this culture of intolerance and violence in society.”

When asked how the government’s new Plan for Combating Fatal Violence Against Children and Adolescents would work to eradicate systemic racism within the Military Police–as racial profiling is now increasingly recognized as severe, for example with Amarildo’s disappearance in Rocinha and the murder of dancer DG in Pavão-Pavãozinho–Minister Salvatti said police brutality is on the government’s radar.

She said: “Besides the necessity of integrating the authorities–which is a policy here in the southeast–like the National Force, the Federal Police, the Military Police, and others, there is also a discussion about creating some kind of mechanism to monitor state police forces because often the comptroller’s office does not adopt the appropriate policies to prevent situations like Amarildo’s.”

The minister added that the study lacked a robust database because municipalities often fail to input information into their systems. She pointed out that this is also an issue that will be addressed in the Plan for Combating Fatal Violence Against Children and Teenagers, which should be implemented later this year.

Below are some of the graphs produced in the report. Read the full research here (in Portuguese).