On Wednesday July 1 the Brazilian Congress rejected a proposal that would lower the age of criminal responsibility for heinous crimes from 18 to 16. Congress members spent all of Tuesday June 30 discussing the proposal and the voting started just after midnight of July 1. The count was close as the minimum number of votes required was 308 and 303 voted to approve it. Three congressmen abstained and 184 voted against.

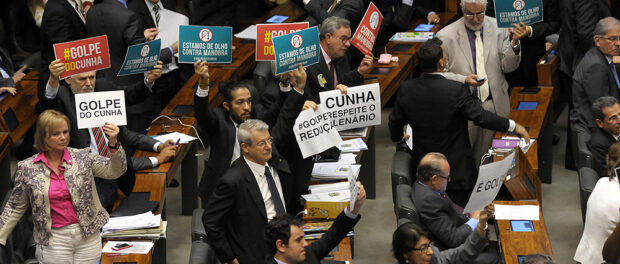

Immediately after the vote, however, in an unprecedented move, Congressional President Eduardo Cunha submitted a similar proposal to the floor to be voted on yet again, with minor changes involving the exclusion of drug trafficking and burglary charges.

Congressional representatives then spent the next day, until just after midnight tonight, July 2, in a hot debate over the changes. Finally, 323 voted in favor, 155 against, and 2 abstained. The new version was passed, pending a second round of analysis and Senate approval.

The vote has received additional levels of attention because of recent heinous crimes allegedly committed by minors, including the murder of physician Jaime Gold in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro. The issue has taken social media by storm and a Datafolha poll published on June 21 revealed that 87% of Brazilians are in favor of the age reduction.

Community Responses

Community leaders and favela residents mostly rejoiced at the initial results yesterday but many admitted there are people in their communities that are pro-reduction.

Activist and member of Complexo do Alemão‘s Coletivo Papo Reto Raull Santiago said: “This is the moment to pause briefly and continue to fight… It’s reinforcing a movement that has to be even more intense, that needs to provoke thinking and multiply understanding of why lowering the age of criminal responsibility is not a solution.”

Photographer, actor and guide Felipe Paiva from Vidigal in the South Zone speculates that the attempt to reduce the age of criminal responsibility is the first step towards privatizing prisons: “I believe that this need to reduce the age of criminal responsibility is only so we can create more prisons, private prisons which would generate a lot of money for their owners. There is no plan for improvement of our prison system. People who are pro-reduction say that, in other countries, the age of criminal responsibility is 16. However, in those countries there are public policies so that the number of homicides and other crimes are lower. There are public policies that can place the young person on another level. And here, there are several statistics that show we don’t have proper infrastructure for young people who are arrested. It’s absurd, it’s a step back.”

Rafael Massena, 27, is in his last year of university and plans to pursue a doctorate to be a university professor. He lives in Complexo da Maré, a complex of favelas from which the military just withdrew its presence. He believes that most of the people in his community are in favor of a reduction because they are looking for a simple solution to end crime and they only watch television news.

[People in my community] have a limited vision of reality and reducing the age of criminal responsibility is the most simple thing,” he said. “I think public education needs to stop focusing on training people to do cheap labor and focus more on thinking. Public education in Brazil, which is accessed mainly by the poor, needs to end the tradition of preparing cheap labor for the market and offer education that develops people’s potential.”

Founder of communication collective Cidade de Deus Acontece and resident of City of God (West Zone) Carla Siccos is against the reduction but says that a lot of people in her community think it’s a good idea. She said: “I am against it, but we know that something has to change. Things can’t stay like they are now. I asked about it on the Cidade de Deus Acontece Facebook page the other day and most people in the community are in favor. People can’t stand minors robbing anymore and not getting punished. I think we all make our own opportunities. I’m against it because I can’t imagine my [16-year-old] son with so much responsibility.”

Cléber Araújo from Complexo do Alemão has been following the reduction since it was proposed months ago. Prior to tonight’s vote, he said: “The big problem I see is that while there are no equal rights, while there is no proper education policy in this country, while there is no bigger commitment with the Statute for Children and Teenagers, there is no point in enforcing such a measure. So my opinion is I am completely against it and the favelas will be the biggest target if this change is made… I celebrated yesterday’s victory a lot but we are anxious because of the new vote so I hope it doesn’t pass and that [the proposal] is banned for good.”

Protests and Child Development Experts Influenced Debate

These two votes and the debate about Brazilian democracy erupting on social media as we go to press, are the result of influential dissenting voices across Brazil’s civil society that have been intensely active on the issue since April.

On April 29, Brazil woke up to decorated streets that expressed young people’s rejection of the proposed reduction of criminal responsibility in a campaign called Waking Up Against Reduction. City squares across 22 Brazilian states were decorated with protest signs in a campaign initiated by students from Rio de Janeiro. In the city of Rio, over 140 squares were occupied by protest signs, including public spaces in the favelas of Cerro Corá, Cidade de Deus, Lins de Vasconcelos, Santa Marta, Maré, Rocinha, Chapéu Mangueira, Cantagalo and Vidigal.

On May 10, Mother’s Day, the campaign organizers called for mothers across Brazil to record videos and take photos showing their stance against the reduction. They also called for mothers and their children alike to flood Twitter, Instagram and Facebook with the hashtag #SouMãeContraARedução (#MothersAgainstReduction).

On June 3, the largest medical association in the country, the Brazilian Pediatrics Society, came out publicly against the reduction, with all participating chapters ratifying the decision.

This week concluded months of protesting and awareness raising about the impacts of reduction on young people’s lives. From a neurological point of view, reducing the age of criminal responsibility means to put an undeveloped brain on trial. According to Science magazine “the brain’s frontal lobe, which exercises restraint over impulsive behavior, ‘doesn’t begin to mature until 17 years of age,’ says neuroscientist Ruben Gur of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. ‘The very part of the brain that is judged by the legal system process comes on board late.'”

Another study by the American Bar Association concluded that “the teen years are a time of significant transition that “demonstrate[s] that adolescents have significant neurological deficiencies that result in stark limitations of judgment.” In addition to this, research shows that when this neurological immaturity is compounded with risk factors like neglect, abuse, poverty and other limitations, it can often “set the psychological stage for violence.”

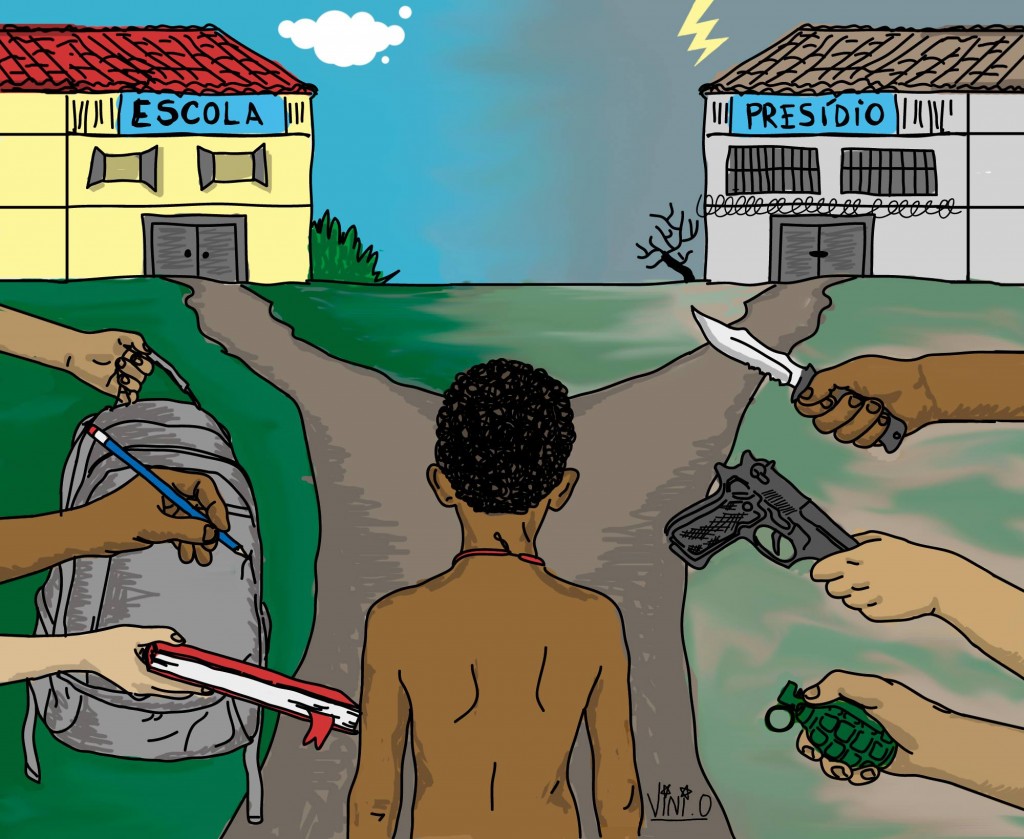

In a piece originally published by Observatório de Favelas and translated by RioOnWatch in May, Alan Miranda argues that the key to avoiding crimes by minors is education, not harsher punishments. He writes: “One study carried out by a former São Paulo organization, FEBEM (State Foundation for the Wellbeing of Minors), concluded that 41% of those who committed a crime had not been going to school before their incarceration. The absence of these youth from school relates to the need to work, with the difficulties in balancing studies and work at the same time, as well as conflicts with teachers and students, and the failures and low quality of education. A study by Professor Vania Sequeira from the Presbyterian University of Mackenzie points out that public policy and prevention are the keys to reducing juvenile crime.”

Miranda also quotes sociologist Eduardo Alves who argues that if the reduction of the age of criminal responsibility is finally approved, authorities will be taking two years of youth away from teenagers. This means there will be less investment in education during the last two years of adolescence. “It is up to adults to create policies to reduce violence and boost culture and rights for young people,” he says. “If it is the adults’ responsibility, then why knock two years off adolescence? Why increase punishment time for those who are not primarily responsible?”