For the original in Portuguese by Fantástico in February 2014 with video, on G1, click here.

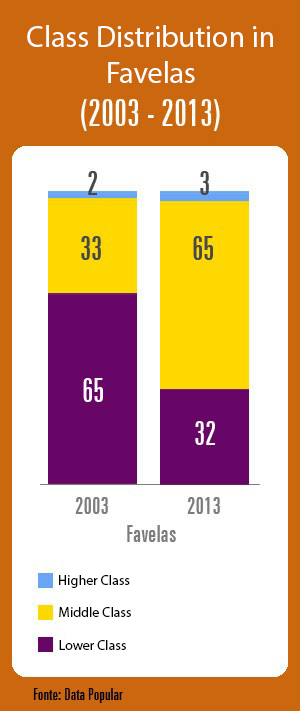

DataPopular surveyed 2000 people in 63 favelas in Brazil. The survey also revealed that 65% consider themselves middle class.

Our team traveled the country in order to create a portrait of Brazilians moved to happiness.

What good might there be in living in a favela? “I prefer to be rich among the poor, than poor among the rich,” said the social worker José Fernandes Junior.

And if it rained money? “I don’t know. Where would I go? A million, I can get by working hard,” said Adriano Castro.

Why don’t young people want to leave? “I tell my friends that Paraisópolis is starting to look like Las Vegas. It really is. You could come here at 3am and see a ton of people in the street. Here, they don’t sleep,” explains motoboy José Lopes da Silva.

They don’t sleep, they don’t stop, and they won’t accept being stereotyped any longer.“’Ah, living in a favela is for poor people,’ No. I don’t feel that way,” affirms Diego da Lima Silva, 22.

Diego and Júnior live in Paraisópolis, São Paulo. Fernandes and Adriano in Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro. But it could be in Buraco Quente, on Santa Teresa hill in Porto Alegre, where Franciso lives.

“Everything I have, everything I was able to achieve here, I owe to Buraco Quente,” explains the shopkeeper Francisco Carlos Ferreira.

Or Alto Zé, in Casa Amarela in Recife, where Keyla and Marcone live. “I never had a bicycle in my life. I finally came to own one when I was over 20 years old, and I bought it myself. With my daughter, it will be totally different. It already is. So I am already happy about that,” says the musician Marcone Santos.

Things are different to the point where Brazil’s 11 million favela residents no longer see themselves like they used to.

Let’s consider the following division of classes: upper class, upper-middle class, middle class, lower-middle class, and lower class.

The majority of residents who responded consider themselves middle class.

These were the findings of the DataPopular Institute in a survey of 2,000 people in 63 favelas across Brazil: 65% said they were middle class, which confirms the signs of prosperity seen in a consumer market estimated at R$63 billion (US$20 million).

“Great happiness from being able to buy my own things I have. And when is it low? When I go to pay. The credit card bill comes and we are wary to pay it!” jokes Marcone.

Marcone, known in Alto Zé do Pinho as Canibal, is a musician and depends on the uncertain income from his shows. But his wife, Keyla, works as an executive secretary and, at night, makes special-order cakes.

Fantástico: Do you make more as a secretary or by making cakes?

Keyla: With both. I’ve had months where the earnings were equal.

Which reinforces another statistic from the survey: in 38% of cases, the primary breadwinner in the family is female.

“The woman is the more rational half of the couple. So, contrary to the common idea that the woman just wants to spend, in the favela things don’t happen this way. The woman is more likely to pay the bills as a result of having had more schooling than the man. She is able to put on the brakes when her husband wants to bite off more than he can chew,” says Renato Meirelles of the DataPopular Institute.

This is the case with Adriano and Luísa. The couple has two restaurants in Rocinha to serve a large number of customers.

“He wants to eat well, drink, dress well. He wants to spend,” says Luísa Paiva.

Adriano wants to turbo-charge the menu with the best offerings, but it is Luísa that holds the keys to the safe.

The couple lives in an alleyway in Rocinha. From the outside it doesn’t look it, but Luísa’s thriftiness has provided them with a well-equipped house. “The house is divided into two floors, two rooms, where my husband, my baby and I sleep. And below is another room with my machine, stove and refrigerator.”

Such houses are common in favelas throughout Brazil. In Porto Alegre, the problem is what is outside the house. The water pipe does not come from the water utility. It is a gato–a counterfeit utility connection. It was the residents who set it up. The same occurs with the electricity. Everything is a gato. The energy utility doesn’t enter the community. But the shortage and scarcity stop at the front gate. Once inside, we can see clearly the contrast between the absence of the State and the strong presence of the people and the families.

Everything shining new. In each room, the same neatness. But how to make sure everything that was bought continues to work?

The housewife Silvana Damasceno went an entire day without water. “Now it is coming. During the day, there’s no water. And at night, no light,” she says. “Now it is showing signs of life. Today it was two in the morning and we had no water,” she explains.

With electricity it is worse. Silvana uses a fan to measure it.

Fantástico: So you mean that if the fan is running strongly, you run to turn on the washing machine?

Silvana: Exactly!

Fantástico: That it’s a sign the power is good?

Silvana: Yes, that it’s good.

Fantástico: And if it’s weak, you just let the dirty clothes accumulate?

Silvana: Don’t even think about it.

People carry on. For the kids, of course, soccer is a source of fun. A worn-out field, with a view of the World Cup stadium in the background–is normal scenery for a favela. But who would have imagined a house with a swimming pool at the top of a favela?

“It was a struggle to carry the pool over the houses, but it’s here,” says the owner of the house, Elisete dos Santos.

Fantástico: For kids to have fun, they don’t even need to leave the neighborhood then?

Elisete: Definitely not. When the neighbors go to the beach, we prefer to stay here.

The survey by DataPopular shows precisely that people are going outside the favelas less and less in order to have fun.

“Think about it: I am close to my house, I am not going to spend a lot, I am safer here than outside. So why would I leave?” questions Diego.

Diego meets up with friends to start the night with dancing and video games. Later, around midnight, he heads out into the street, in Paraisópolis, where everything is happening.

According to the survey, the most popular form of entertainment for a favela resident is to go to a party within the community: 45% of residents do this every month; and 36% have a barbecue once a week inside the favela.

Almost no one is seen in the darkness of the streets and alleyways of Rocinha. But it is just the start of Sunday night, when people are beginning to prepare for the night ahead, and this happens indoors.

Here, barbecuing is an institution. The businessman João Batista receives people at home all day.

Fernandes is an expert in having fun in the favela. “Having fun means meeting people, it means meeting someone else, connecting with them, having awesome experiences, creating friendships, and making more friends throughout life.”

What interrupts these get-togethers, at times, is the tension created by violence, such as the shooting that occurred in Rocinha in the early morning of Sunday, February 16, 2014.

As if there were two worlds existing side by side, in the world of amusement there isn’t the slightest indication of violence.

Fernandes organizes a pagode samba party that packs the street–soon the funk music starts. “Rocinha is, and will always be, a big mixture. Without funk and without pagode, no event is good enough. There isn’t an event in Rocinha that doesn’t have this mix,” he explains.

In the favela, funk begins in infancy. It’s a fever among kids. But, with 16% saying it is their favorite genre of music, it is not the most listened-to style of music in the favelas. Pagode, with 30%, is in first place.

Even in the south of Brazil, a good party has samba and meat on the grill. “Here, we have a tradition of swing dancing that has spread throughout Rio Grande do Sul. People sometimes forget it, saying that gauchos don’t know how to dance samba, but we have a tradition of barbecue linked to samba,” says Diogo Santos da Fonseca.

Whatever the entertainment may be, it is always communal. The survey showed that 70% of residents host friends, relatives or neighbors every month.

“If you run out of sugar or coffee, you go out on your porch and shout to your neighbor: ‘Can I have a cup of this, a cup of that?’ And sometimes, you intervene in the stress of your neighbor’s house and help pacify a situation–this doesn’t happen in a condominium. This intimacy, this value of being together, this affection for your neighbor, this is something you only find in the favela,” emphasizes Fernandes.

There is a clear perception that this doesn’t happen when you go outside the favela.

And this is why so few people want to leave the favela. “The survey shows that more than two-thirds of favela residents would not leave the favela even if their salary doubled. This means, in practice, that this community-centered lifestyle is present in the day-to-day life of the more than 11 million favela residents in Brazil,” explains Renato Meirelles.

“The majority of people who left, I would say in the 35 years that I have been here, have come back. If it was so bad, why would they come back?” asks Francisco.

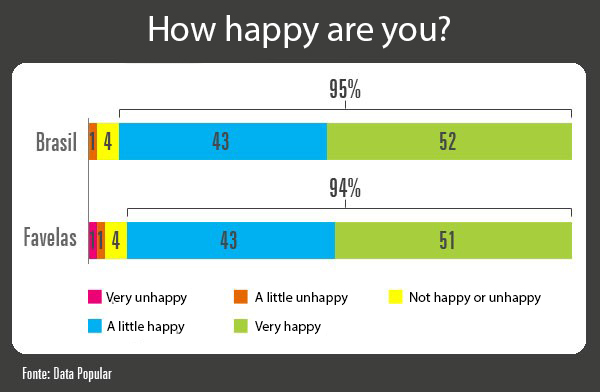

And 94% of favela residents state that they are happy.

“To be happy with yourself is a big accomplishment as a person,” assures Marcone Santos.

“Happiness comes from simplicity,” says Fernandes.

“Happiness is in the people. It is in the people and the families. That’s why I think poor people, they know how to live. I think they are happier than even people in other places,” concludes Francisco.