This post is the third of four RioOnWatch contributions to Blog Action Day 2015 in which bloggers around the world reflect on this year’s theme: Raise Your Voice. Check out our full series here.

Every day, young communicators from favelas experience the pain and joy of reporting their reality, bringing to light a media form that is no longer seen as a longed-for necessity but which has become a reality in the favela territories, exposing the real day-to-day life there and placing residents as the main characters. Some call this community, alternative, or popular journalism. Others only understand the term once they are involved.

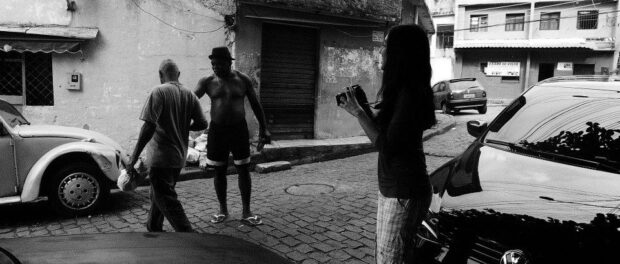

Issues are covered carefully and events are critically observed and understood. With a notebook, a pen, and a cell phone, we trail through the alleys in search of news, stories or cultural events. We stand on the side of human rights. We fight for life.

Based on local knowledge and work on-the-ground, we fill ourselves with hope instead of conforming ourselves to the difficulties we face. They work to incentivize us to ask ourselves: if we don’t share this news, who will? In what way can we, residents, change our reality through words?

With the countless violations of rights that happen in our favelas, our job as community journalists is to intervene, question and denounce. For example, the article Maré Cracklands: Three Years of Neglect by the Authorities published on RioOnWatch presented a problem that’s existed for years and demanded solutions. Drug users who live in this environment don’t receive any support for their recovery. The importance of this and other issues is due to their serious nature. The community journalist’s interest in exposing situations of such high impact on the life of his or her favela is natural, as in the case of this crackland.

Local outrage and widespread visibility generate impact. Community reporting leads local residents to be seen as protagonists who support and spread news. And when the international media support community journalism, the problem is highly exposed and its solution facilitated.

Another case is the article Maré Calls for Basic Sanitation published on Viva Favela which exposed the reality of the community, contradicting claims made by the City in their advertisement regarding the new trash collection system. The publication of this article resulted in the mobilization of Comlurb, the waste collection service, to make improvements in more precarious areas.

“Local outrage and widespread visibility generate impact. Community reporting leads local residents to be seen as protagonists who support and spread news. And when the international media support community journalism, the problem is highly exposed and its solution facilitated.”

As a result of the global attention Maré received during and following its military occupation, many promises were made by the authorities. The Nave do Conhecimento (Knowledge Ship community learning center) merits attention. However, without residents following up on the case–due to their lack of awareness of the promise published on the City’s institutional site–the questioning of the absence of the science and technology educational center only took place following an article published by a community journalist. This was able to bring awareness to the community, open people’s minds, and was arguably more powerful because it came from the community itself.

The goal of publicly communicating situations is to deconstruct stereotypes, give voice to community residents and present a viewpoint from the inside to those who don’t know. This work is small, has needs, and depends on the desire and faith that changes will happen, be it collectively or in the personal, intellectual, moral, or social development of individuals. Informing people in this manner is the only alternative journalists from low-income areas have to gain freedom in the subjects they choose to report on and not lose their ideology to the world of large (dominant media) corporations.

In practice, the authorities are not concerned with the direct impact of these articles. But the alternative vehicles that publish them contribute to a society that deconstructs certainties and considers issues with more than just preconceived ideas. Brazil’s Youth Statute supports all of this. It affirms the right of young people to be informed and express themselves, in addition to defining measures so that our viewpoints are transmitted.

“The goal of publicly communicating situations is to deconstruct stereotypes, give voice to community residents and present a viewpoint from the inside to those who don’t know…In practice, the authorities are not concerned with the direct impact of these articles. But the alternative vehicles that publish them contribute to a society that deconstructs certainties and considers issues with more than just preconceived ideas.”

A young person in the favela will not stay quiet as long as the means to raise their voice and resist a State that oppresses them exists. Published articles are only one step in this journey, in the struggle for rights and for life. We know that resistance is worth it!

Thaís Cavalcante is a 21-year-old community journalist, born and raised in Nova Holanda, one of the favelas in Complexo da Maré. Working as a community reporter over the past 4 years in her community, Thaís decided to study journalism at university and believes in the power of information to change our reality.