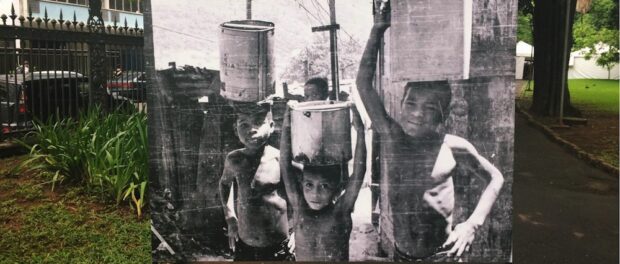

An exhibit now in its final days at Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of the Republic presents a small taste of the photographic archive of Anthony Leeds, a prominent American anthropologist celebrated for introducing urban anthropology to Brazilian academics during the 1960s. Curated by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz, Brazil’s equivalent to the National Institutes of Health), the collection includes a carefully selected subset of his 770 images donated by late Professor Leed’s widow, political scientist and Brazilianist Elizabeth Leeds. The exhibit, entitled “O Rio que se queria negar” (The Rio that wanted to deny itself) beautifully illustrates Anthony Leeds’ contributions and the communities he so admired, while bequeathing upon cariocas (Rio locals) a historical treasure.

The photographs document daily life in the communities Leeds frequented while conducting fieldwork on the favela economy. Striking black and white images of children playing in streets, favela topography and construction, women cooking in their homes, and communities organizing around construction and holding elections for residents’ associations adorn the three rooms in the museum and the central walkway, a perfect setting for reflection in the museum’s lovely garden. The names of the favelas Leeds studied are painted on a wall inside.

Many of these images provide one-of-a-kind documentation of favelas that were later removed and whose visual history would be otherwise lost including the Macedo Sobrinho favela in Humaitá, removed in the late 1960s. At a time when policies prioritized removing favelas from Rio’s South Zone and relocating residents to housing projects on the urban periphery, Leeds recognized the value of favelas. Elizabeth Leeds told RioOnWatch: “one of [Tony’s] main messages was that favelas were the solutions, not the problems. What the wider middle and upper classes saw as misery, poverty, fragility, he saw as creative and innovative. For example, he saw the gardens and animal keeping in the favelas [including pigs] as an important part of the favela economy.”

Many of these images provide one-of-a-kind documentation of favelas that were later removed and whose visual history would be otherwise lost including the Macedo Sobrinho favela in Humaitá, removed in the late 1960s. At a time when policies prioritized removing favelas from Rio’s South Zone and relocating residents to housing projects on the urban periphery, Leeds recognized the value of favelas. Elizabeth Leeds told RioOnWatch: “one of [Tony’s] main messages was that favelas were the solutions, not the problems. What the wider middle and upper classes saw as misery, poverty, fragility, he saw as creative and innovative. For example, he saw the gardens and animal keeping in the favelas [including pigs] as an important part of the favela economy.”

The images displayed in the exhibit capture the dignity and resilience of favelas at a time when many were denied recognition by the government. In a fitting tribute, the lyrics to the iconic samba composer Zé Keti’s “Opinião” (Opinion) are displayed between portraits: “They can beat me, they can arrest me; They can leave me without food; I will not change my mind; Here on the hill I will not leave, no.”

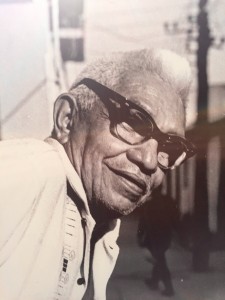

The photos also capture a sense of the people and places that became important to the Leeds. Both Americans, the couple met in Rio in the mid-1960s while he was doing field work and she was a Peace Corps volunteer. Elizabeth Leeds’ favorite photo is one of the favela where she lived, Tuiuti, which features a bust of President Getúlio Vargas in a window. She recalls that a portrait of Flavio Ramos from Jacarezinho was a photo that Anthony particularly liked. Flavio “provided many insights that Tony thought [were] brilliant,” leading the anthropologist to refer to Flavio as “the professor.”

The photos also capture a sense of the people and places that became important to the Leeds. Both Americans, the couple met in Rio in the mid-1960s while he was doing field work and she was a Peace Corps volunteer. Elizabeth Leeds’ favorite photo is one of the favela where she lived, Tuiuti, which features a bust of President Getúlio Vargas in a window. She recalls that a portrait of Flavio Ramos from Jacarezinho was a photo that Anthony particularly liked. Flavio “provided many insights that Tony thought [were] brilliant,” leading the anthropologist to refer to Flavio as “the professor.”

“The photos were as important ethnographically as written text,” Elizabeth explains. She donated the photos and negatives, along with several hundred slides of Rio and other cities across Brazil and Latin America, to Fiocruz because she knew the Rio institution would “treat the materials respectfully and would make them accessible to the public.” Her hope is that “visitors will see the images with the same sensitivity that Tony had in taking them.”

The exhibit beautifully celebrates the work of a man who has since influenced generations of anthropologists and sociologists to study favelas. It also takes an important step in recognizing the failings of past policies. The government’s refusal to honor favela rights and recognize favelas for their assets by supporting asset-centered development models, has led to mass evictions and exacerbated social stratification within the city. It seems a particularly appropriate time to acknowledge the flaws in this approach as Rio de Janeiro is currently experiencing the largest wave of favela clearances in its history, including those of favelas Leeds documented that were removed by the military dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s. Considering many favela residents continue facing similar challenges to those of fifty years ago, reflecting on Anthony Leeds’ work couldn’t have come at a better time.

The exhibit beautifully celebrates the work of a man who has since influenced generations of anthropologists and sociologists to study favelas. It also takes an important step in recognizing the failings of past policies. The government’s refusal to honor favela rights and recognize favelas for their assets by supporting asset-centered development models, has led to mass evictions and exacerbated social stratification within the city. It seems a particularly appropriate time to acknowledge the flaws in this approach as Rio de Janeiro is currently experiencing the largest wave of favela clearances in its history, including those of favelas Leeds documented that were removed by the military dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s. Considering many favela residents continue facing similar challenges to those of fifty years ago, reflecting on Anthony Leeds’ work couldn’t have come at a better time.

The exhibit will be open to the public at the Museum of the Republic until January 10, 2016.