The notion that the working poor do not pay their fair share of taxes remains a common and enduring talking point amongst conservatives around the world. Here in Brazil, this stigma is often used to widely justify the lack of adequate services, healthcare and adequate housing available to large segments of the population, many of whom live in favelas. This misconception is further exacerbated by the overwhelming presence of the informal sector, which analysts believe accounts for over 48 million workers and around 60% of the nation’s total employment.

But to argue that those employed informally do not pay taxes is to overlook the systemic policies of regressive taxation fundamental to Brazil’s notoriously complex tax code. By definition, regressive taxes are those that impose a greater relative burden on people with a lower ability to pay. In practice, they are most often levied as non-uniform consumption taxes on basic essentials. Research has shown that the products taxed most regressively in Brazil are basic foodstuffs, cooking gas, electricity, clothing and tobacco, all products heavily utilized by the working poor.

Overtaxing the poor on their consumption of basic goods is not the only questionable aspect of Brazil’s tax code. Further digging into the nation’s tax legislation reveals a flawed system that, since its inception in 1988 with the ratification of the nation’s new Constitution, has remarkably managed to impose a gross tax burden on par with countries in Northern Europe but sustains inequality rates similar to those found in Sub-Saharan Africa.

An economist employing a bit of dark humor might call this paradoxical relationship the Brazilian Miracle, round two. The prevailing logic amongst tax policy analysts has always been that a strong correlation exists between high gross tax burden as a percentage of a country’s GDP and low Gini coefficients—the metric used to determine inequality. Brazil seems to have been able to buck this trend by enacting a tax code that is fundamentally biased against the poorest members of society.

The root cause of this counterintuitive phenomenon again lies in the types of taxes levied. In Brazil in 2011, indirect taxes on consumption—the aforementioned regressive taxes—accounted for over 49% of the gross tax burden, compared to just 34% in OECD countries. In contrast, rates for taxes that predominantly affect the wealthy, like estate and capital gains taxes remain comparatively very low. A progressive wealth tax that would tax individuals with assets over R$2 million—the Imposto sobre Grandes Fortunas—has been discussed for over 20 years but never implemented.

A major source of stigmatization results from confusion surrounding people who do not pay income tax but are still subjected to a large overall tax burden. This prejudice is not unique to Brazil—U.S. presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s infamous “47% of Americans don’t pay taxes” comment, often cited as the reason for his 2012 election defeat, is a prime example.

It is true that most citizens who work informally do not pay income taxes, but income tax makes up a mere 19% of total tax revenue in Brazil. There is also hardly any incentive to enter the formal economy and pay when the tax brackets have been designed in a skewed fashion that makes their function—the true redistribution of wealth—unattainable. Because the system consists of multiple tax brackets, it maintains the guise of being progressive, but by setting the threshold of the highest bracket to a relatively low income level, the poor and middle class are penalized while the wealthiest families enjoy comparably tiny tax burdens.

All annual incomes over R$49,051 are currently taxed equally at a rate of 27.5%. Translated to US dollars, this means a person who makes US$15,000 per year is taxed at the same rate as a person who makes $15 million. In comparison, rates for the highest earners in the US, much of Europe and other developed nations range from 40% to 57%.

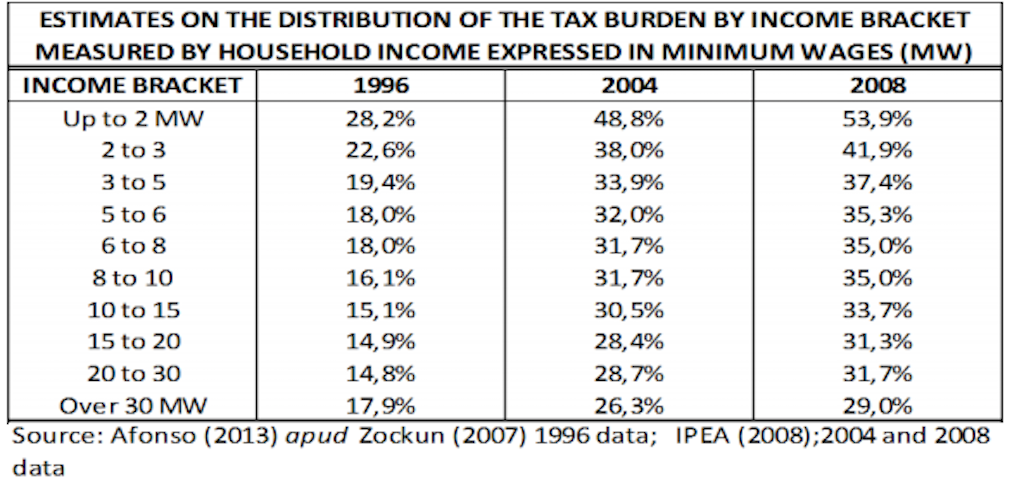

The situation is only getting worse. According to various research reports, from the mid-1990s to today, families earning up to two minimum wage salaries have seen an increase in their direct tax burden while those who earn over 30 minimum wage salaries have received a reduction. For corporations, the tax landscape is similarly biased to help multinationals and large corporations instead of small businesses. Despite wide-ranging efforts by the federal government to formalize them, it is easy to see why many small enterprises in Brazil often choose to remain in the informal sector. The World Bank ranks the nation 126th in “ease of starting a business” and a 2013 Forbes study found compliance with the tax code to be more time-consuming than any other country in the world. Likewise, small businesses face a higher relative tax burden than large corporations, which inherently encourages the informal economy to flourish.

In such an inequitable system, why does the misinformed rhetoric and stigmatization persist? The extreme complexity of the tax code is thought to be a major factor in stymieing the acceleration of social movements for tax justice. Likewise, the public association of the informal economy with criminality is deeply-rooted.

If Brazil’s government is truly as interested in economically integrating the informal sector as they claim to be, it is clear that they must first take steps to overhaul the nation’s biased tax code.