For the original article by Jessica Mota in Portuguese published by Agência Pública click here.

Residents of the West Zone resettled through the Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) federal housing program are receiving unauthorized charges from Banco do Brasil, generating insecurity and fear; some are getting a bad credit record with the SPC Brasil credit bureau.

When they were forcibly removed due to the construction of the TransOlímpica Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line, the former residents of Rua Ipadu, São Sebastião and Vila União de Curicica–favelas in Rio de Janeiros’ West Zone–did not have many options. The evictions started in 2014 and the changes in residence occurred in early 2015. Some were offered compensation which did not allow them to buy a property in the region, but most accepted to leave their homes in exchange for an apartment in one of the condominiums built by the federal government’s Minha Casa Minha Vida program, which is administered by the city.

“At the time of expropriation, [the City] promised they would pay, but our problem was that they didn’t put anything in writing,” says Jorge Valdevino, representative of the Colônia Juliano Moreira Condominium, where residents were relocated. The Municipal Housing Secretariat (SMH) reports that 96 families were resettled to that residence.

The removal process, with notification to the residents, began in 2013 to make way for the TransOlímpica, considered one of the legacies of the Olympic Games in Brazil. A three-lane highway with one lane exclusively for the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), the route connects the neighborhoods of Deodoro and Barra da Tijuca in the West Zone. The Consortium Via Rio, composed of CCR, Odebrecht and Invepar manage the project. In the contract with the City, the consortium was responsible for registering families to be removed, demolishing houses and relocating the residents.

Agência Pública went to Colônia Juliano Moreira and interviewed 17 residents from different condominium blocks. All reported the same situation: after more than a year living there, to this day they do not have copies of contracts for the apartments. In addition, six months ago some residents began receiving collection letters from Banco do Brasil, which financed the construction of the condominium, informing them they owe a debt of R$75,000.

“The letter didn’t even come here, it went to where I used to live, and my mother delivered it to me. The letter said I owed R$75,000. The last time I consulted my record with the SPC [Credit Protection Service], [the debt] was around R$69,000,” says Ozineide Pereira da Silva, a 30-year-old manicurist.

“We signed the contract and went to City Hall. The bank was there, there was a security vehicle, they had all the envelopes, all nice and neat. Everything was all sealed, they opened them in front of us. We signed a lot of paper, lots of sheets of paper, but they didn’t give us any copies,” she recalls. She lived with her three children, disabled grandmother, mother, sister and her four children in a room in the occupation of an old scarf factory on Rua Ipadu. With the removal, her mother and sister had to “hunt out a corner,” as she describes it. Now she lives with her three children and grandmother, who she cares for, in a two-bedroom apartment. For Ozineide, who lived in the shed of an abandoned factory, the new apartment was very good. “The only fear we have is due to the bank putting our name on the SPC and the fear of, I don’t know… after the government changes… I have nothing to say that this is mine,” she says.

Antonio Zacarias da Silva, 40, lives with his daughter and wife. He received two letters from Banco do Brasil informing of a debt of R$70,000. “I don’t know what the letter said because I cannot read. My wife can read,” he says. Without information Antonio interprets the collection notices as eviction letters. “We will have to vacate the apartment,” he believes. He lived on Rua Ipadu and works carrying debris and moving furniture with his horse Xuxa, and cart.

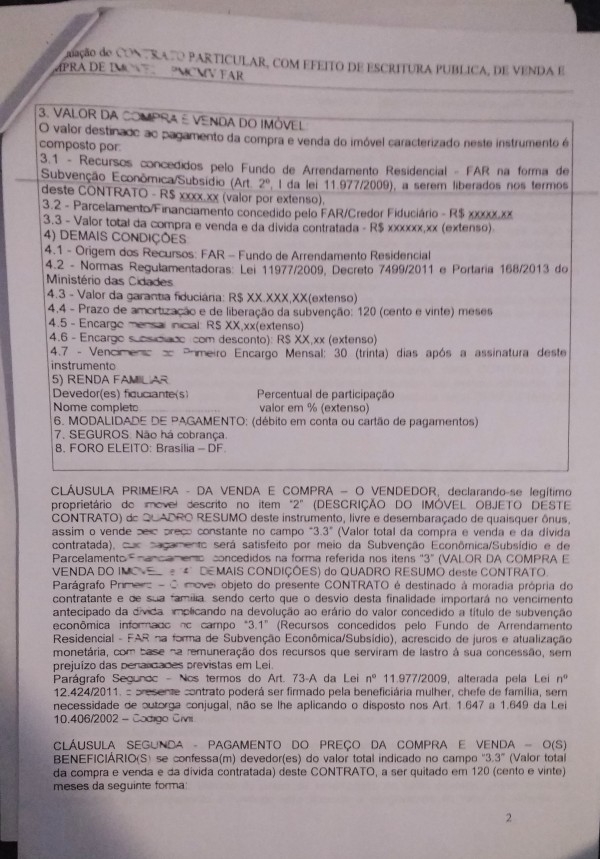

Creuza da Silveira and her mother, Conceição de Oliveira, also lived in the occupation on Rua Ipadu. Creuza is illiterate and received collection letters for R$76,000. Her son knows how to read. “I have a bad credit record, it is written in the letter with my identification number.” The only document they gave her was a copy of a generic Minha Casa Minha Vida contract that instead of showing names and values, contains a sequence of crosses and blank white spaces.

Elaine Santos, 34, a former resident of Rua Ipadu, hasn’t received collection letters, but already feels affected by the climate of uncertainty. “I am not even producing milk anymore because I’m stressing so much. Not even milk,” says the mother of five children, including a baby less than a month old. “I am not going to lie and say that it was beautiful [at the occupation on Rua Ipadu], it was ugly. But there, it was quiet. It was ours. And here no one has documents and now there’s this rumor that they want to take it away… How we will prove that this is ours?” She said she signed the contract, but did not receive a copy from the City.

After the first interviews at the Colônia Juliano Moreira Condominium, many residents contacted Agência Pública’s reporters and confirmed the climate of fear, insecurity and anger because of the situation. Many fear losing their homes because they have no way of proving they own the apartments.

Isabela Cristina Oliveira Santos, 22, says her sister tried to register proof of the signed contract. “My sister signed and could not take photos because they said she had to wait. With this wait, she now has a bad credit record.” Isabela reports that she still has not signed any contract until today, even having given all the necessary documentation to the City. “We’re waiting to see when we will be able to sign the Banco do Brasil contract. When I contacted Serasa [credit agency], there was no information. We call the City almost every day. They say we have to wait because the documentation is all with the bank. They never tell us anything.”

Giselle Murad da Silva, a 22-year-old teacher, found out she had a bad credit record when she applied for a job in the public sector. She lived with her mother, Sandra Murad da Silva, 47, in the Vila União de Curicica favela in a house with garden, pantry, living room, bedrooms and terrace. Sandra was a resident of Vila União de Curicica for 27 years, until the arrival of the TransOlímpica. Like other residents of the Colônia Juliano Moreira Condominium, the only document for the apartment she owns is an unsigned template contract with blanks.

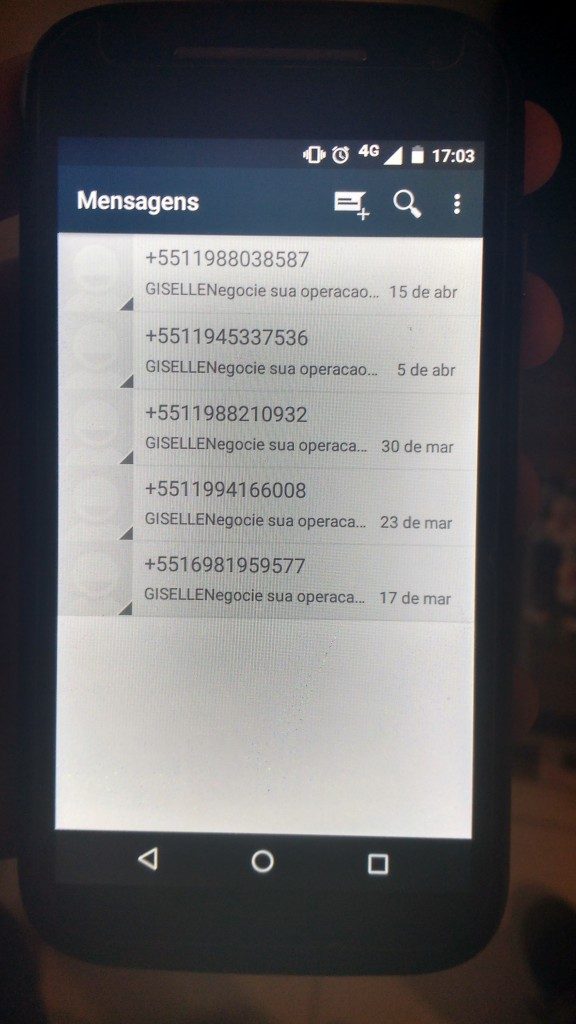

“It was all done by the City with Banco do Brasil. She gets emails all the time, and we get letters with charges saying we owe R$75,000 to Banco do Brasil. But we owe nothing, we exchanged key for key,” says Sandra indignantly. Giselle complains about the bank’s harassment. “They call me, send me messages on my cell phone. I have several messages from Banco do Brasil saying I need to settle my debt. But I have no debt with Banco do Brasil. I don’t even have an account with them.”

Their neighbor, who also lived next door in Vila União de Curicica, José Pereira Filho, 52, suffers the same problem and says he is disappointed. “I have been more than 20 times to the sub-mayor’s office [for Barra da Tijuca and Jacarepaguá]. I was ignored. Only they have my documentation. They did not give me any paper at all. I believed in the City’s word,” he says.

In Vila União de Curicica, outside the house where he lived with his wife and son, José maintained a mechanical workshop autonomously. He says he was not compensated for the workshop, lost tools and mechanical equipment and is now unemployed. “We signed a lot of documents collectively, there wasn’t time for anyone to read them. The mayor [Eduardo Paes] promised it was an exchange of keys, it would be settled with the apartment, that we’d receive a provisional deed and after ten years it would be finalized. What we received was the full charge of the value from Banco do Brasil, as if we’d bought the apartment.”

According to Paulo Magalhaes, a sociologist and former advisor to vice-president of Caixa Econômica Federal, the bank responsible for most Minha Casa Minha Vida condominiums, “[In Colônia] it was done by Banco do Brasil, but the procedure is the same. Only Banco do Brasil doesn’t have the same bureaucratic experience with these documentation procedures.”

In the housing program’s standard contracts, people pay subsidized installments and after five years receive the title deed for the apartment. In the case of those who were resettled by the City in the “key for key” manner–they lost their homes, which would be demolished in exchange for housing through Minha Casa Minha Vida–the obligation to repay the installments lies with the City government. The debt with residents should not exist. “If your house was destroyed, you do not pay. Of course, this is a cross-financial transaction. Someone has to pay,” said Paulo Magalhães.

“In theory, when people move into the property, when they get the keys, they sign a contract. This agreement is important because even if you do not have the title to the property, the contract is your guarantee,” says Magalhães. This contract should be named and signed by the bank, by the City and the resident.

When A Pública asked Banco do Brasil to clarify the situation, they refused to give interviews and responded: “We fulfilled all our obligations to date and await the public entity to rectify the situation.” The bank did not respond to A Pública’s questions about why they had not delivered copies of the contracts to residents.

The Rio de Janeiro Municipal Housing Secretariat (SMH) said in a statement that the mess was created by the bank’s delay in releasing information on the contracts’ payments. The department says: “The payment of installments for properties of those resettled in the Colônia Juliano Moreira Condominium is being regularized.” After “understandings” between the Banco do Brasil and the public agency, the information is that “the issue is being looked into so that the transfers are made.”

The SMH informed that the documentation for the apartments will be delivered after being registered at the notary office, but did not say when that would be.

Beth McLoughlin contributed reporting.