The criminalization of poverty is a global phenomenon of mistreatment and prejudice faced by the poorest members of society due to their economic circumstances, often influenced by and perpetuating racism and other forms of discrimination. It can manifest itself in various forms, with common examples including excessive fines for petty offenses, laws and policies aimed at “cleansing the streets” of homeless people, arbitrary surveillance, unlawful arrests and, in its most sinister form, physical violence or murder. This article aims to outline the many forms in which low-income Brazilians have been, and continue to be, subjected to unjust treatment by the government, legal and penal systems, police, and mainstream media.

Historical Background

In Brazil, the marginalization and criminalization of the poor has a foundation that dates back to the origins of the country itself. In its early history, the country’s economy heavily utilized slave labor, importing more slaves than any other country in the world—roughly ten times more than the United States. A small population of landowners—often lighter-skinned—amassed and consolidated large amounts of power and territory, creating a systematically entrenched gap between those who controlled the land and means of production and those who did not.

When the Portuguese court arrived in Brazil in 1808, enslaved people made up more than half of Rio’s population; concerns about rebellion against the minority elite led the Prince Regent Dom João to create the Military Division of the Royal Police Guard. RioOnWatch contributor Patrick Ashcroft writes that “essentially the Guard’s mandate was to subjugate and repress, protecting the dominant elite and quashing any potential uprising.” The very origins of today’s Military Police, then, were to uphold a social hierarchy and control the masses on the assumption that the poor were potential criminals, or at least threats to the status quo.

When Brazil finally outlawed slavery in 1888, meager efforts to integrate former slaves immediately thrust them into a position of disadvantage and poverty. Freed slaves and an influx of migrants from other parts of the country built homes where they could, in an absence of government-planned affordable housing, leading to the emergence of the city’s first favelas. As the nation modernized in the 20th century, a mix of government policies ranging from neglect to repression maintained the poor as a largely marginalized, excluded population.

This divergence between strata of Brazilian society expressed itself in public opinion towards the poor. Writings produced by “architects, social workers, and doctors that entered favelas in the early 1900s” described these communities as “backwards, unsanitary and oversexualized.”

Government discourse was no more nuanced. An 1888 National Congress speech referred to the “poor and vicious classes” and argued that “even when vice is not accompanied by crime,” poverty itself “constitutes a rightful reason of terror for the society.” Terror and disgust in discourse justifies policies in which poor people need to be relocated, policed and controlled, or even eliminated. This logic is evident from this statement from government documents dating to 1930:

“It is favelas, one of the diseases of Rio de Janeiro, in which it will be necessary, soon, to pass the burning iron. Their leprosy dirties the neighborhood of the beaches and the areas most graciously decorated by nature. Their destruction is important not only from the point of view of social order and security, but also from the point of view of general hygiene of the city, with no mention of aesthetics.”

Today, these same notions that poor communities are “dirty” places in an otherwise beautiful city, or that they are the source of security problems, is expressed in both the recent return to evictions policies and the continuation of militarized favela policing programs.

In recent decades, the growth of gang activity in favelas to supply domestic and international demands for drugs led to a societal linking of favelas with drugs and urban violence, even though academic estimates suggest less than 1% of favela residents are involved in drug trafficking. Instead of seeing violence in favelas as a result of systemic inequality, some people consider violence to be an inherent feature of the favelas themselves. Accordingly, favela residents earned reputations for being violent and dangerous, rather than victims of significant historical neglect by the state. Government policy in pursuing a “war on drugs” has been molded by these prejudices, for decades sustaining a reality in which the main presence of the state in favelas was through the Military Police.

Although the Constitution of 1988 promised reforms and benefits for poorer members of Brazilian society, the harsh policing of the military era continued with the pretext of combating gang activity. The “war on drugs” particularly threatens poor, black residents of favelas. Residents, no matter their involvement, remain at risk of being threatened, hurt, or killed, because of their presence in these territories. Many favela residents and observers argue police remain the main representative of the state even in favelas with Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), despite the program’s stated original intention to bring other services alongside security.

Criminalization of Poverty Today

Today, it seems that while wealthy, light-skinned Brazilians can be publicly drunk or rowdy, black and poor youth risk their lives by doing much less. On multiple occasions in recent summer months, poor, majority black youths who had not committed any crimes and were not carrying drugs or guns were detained on buses to the touristic South Zone of Rio as potential criminals. This effort, in theory aiming to reduce crime near the beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema, has been condemned as illegal by judge Pedro Henrique Alves of the First Court of Childhood, Adolescence and Old Age, yet the practice of viewing low-income youth as guilty until proven innocent endures. The assumption of criminality also has an impact in job searches; employers are well known to look unfavorably on candidates with addresses in favelas. Such prejudice, of course, makes it harder for favela residents to find formal employment and further perpetuates stigmas and promotes crime.

Often excluded from public spaces frequented by the wealthy, some low-income youth have taken to social media to organize large gatherings in shopping malls dominated by the rich. These peaceful gatherings, which became popular in 2013 and 2014, are known as rolezinhos. Despite their non-violent nature, rolezinhos are often treated as a disruptive form of protest and have been prohibited in both the cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. On a Sunday in January 2014, the upmarket Shopping Leblon mall closed its doors in anticipation of a rolezinho planned to take place there on that day. After this incident, judge Isabella Peçanha Chagas mandated a R$10,000 fine for each participant in the rolezinho.

But banning rolezinhos is just a small part of the greater war on the poor. Human Rights Watch reports “police in the state of Rio de Janeiro have killed more than 8,000 people in the past decade, including at least 645 people in 2015. One fifth of all homicides in the city of Rio last year were police killings. Three quarters of those killed by police were black men.” A shockingly small number of officers responsible for these killings were prosecuted and among those who were, almost none ended up serving time, even in the worst of cases. For example, in the case of the Candelária massacre in 1993, in which nine suspects opened fire on homeless children sleeping on the steps of the historic Candelária church in Centro, killing eight of them and injuring dozens more, three officers were convicted and given lengthy sentences; however, none of them actually served their sentence. This atrocity is thought to have been motivated by a larger and enduring attempt to “clean the streets” of Rio, efforts that have re-emerged prior to hosting the World Cup and the Olympics.

Rafael Braga—a homeless black man arrested during Brazil’s 2013 mass protests—has become a symbol of the current struggle against the criminalization of poverty. The only person to be convicted for a crime during these protests, the largest of which had over 300,000 participants, he was sentenced for carrying liquid detergent on the basis that it was an “explosive or incendiary device, without authorization or in breach of legal or regulatory determination.” Social media responses and ongoing activism events demanding Braga’s freedom emphasize this case highlights the inextricable links with racism and the criminalization of poverty.

Contradictions in the Law

The Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988 offers protection for discrimination against poverty in Article 3, which calls for a more free, just, and solidarity-filled society (ch. I), the eradication of poverty and marginalization along with a reduction of social inequalities (ch. III), and the promotion of everyone’s well-being, with no prejudice as to origin, age, sex, color, age, or other forms of discrimination (ch. IV).

However, Brazilian legislation also contains some components which reinforce discrimination. Legislation regarding drug use and drug offenses states that location of drug use, as well as social and personal circumstances of the accused, will determine whether or not the drug was intended for personal use (Law n˚11.343, ch. III, art. 28, p. 2). This same law also states that the sentence will be determined according to the “personality and social conduct of the agent” (ch.II of Crimes, art. 42), a factor that can be largely subjective.

Fortunately, this same law also requires the engagement of services and organizations that serve to prevent drug use and promote social inclusion and improvement of quality of life (Title III, ch. I, art. 19, VIII and IX). However these measures are notoriously not effectively carried out in disadvantaged communities, where drug use is more severely punished.

The Federal Constitution of 1988 provides for freedom of cultural expression, “the expression of intellectual, artistic, scientific and communications activities is free, without any censorship or license” (Title II, ch. I, art. 5, IX). However, Brazil contradicted its own constitution once again when it implemented a Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) into the culture of funk in favelas in 1995. Created with the purpose of investigating funk in relation to drug trafficking, it ended in a project of laws that required all future funk parties be authorized and chaperoned by police from start to finish, while pacification brought further restrictions to baile funk parties.

Prison as Incubator of Violence

Brazil’s penitentiary system is another institution fundamental to perpetuating a cycle of poverty and violence that ensnares many young lives. The nation has the fourth largest prison population in the world and of those jailed, 40% have never stood trial, 59% are between the ages of 18 and 29 and roughly 66% are black. 93% of the prison population does not have a high school diploma and around 45% do not have schooling past elementary level. In juvenile detention centers, the educational statistics are even more alarming. These numbers reveal a system that is crippling in its effects on restricting upward mobility between social classes.

Entire families often feel the burden of a single member being imprisoned, with or without cause, because affordable and quality legal aid is difficult to come by in most states and nearly impossible in others. To mount a defense, families are sometimes forced to give up their homes or other basic necessities. Regardless of whether the original individual arrested is guilty of a crime or guilty of nothing more than being poor, black, indigenous or some other label that made him or her a “suspect,” without the money to mount a proper defense, relatives may turn to actual criminal activity in an effort to financially support the jailed accused.

Rather than serve to reform and reintegrate criminals into society, Brazilian prisons are characterized by high levels of overcrowding, insufficient health care, a lack of educational or work opportunities and constant exposure to violence. It is no surprise then that Brazil’s largest drug gangs formed within the prison system and maintain strong influence in prison systems today.

The Complicity of the Mainstream Media

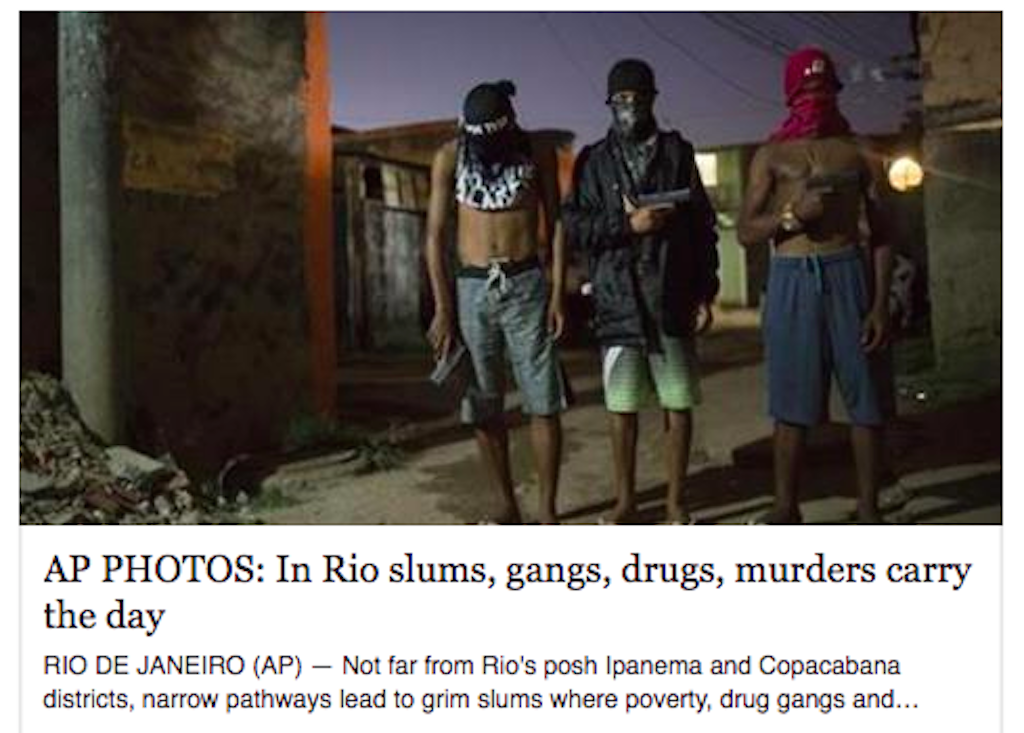

By overwhelmingly representing favelas as dangerous and violent urban spaces and by selectively representing victims and perpetrators of crimes through a racialized lens, mainstream media is tacitly complicit in criminalizing poverty.

Civil society organizations, social movements, and activists have made great strides towards democratizing media in Brazil by harnessing social media and other alternative communication channels. However, a de facto media oligopoly with strongly vested political and economic interests persists. The image of favelas painted by these mainstream media outlets can be characterized as generally negative and stigmatizing.

In an analysis of 640 articles over six months in 2011 from three major Brazilian mass media outlets (O Globo, Extra, and Meia-Hora), Observatório de Favelas (Favelas Observatory) found that “in all six months, ‘violence, crime and drugs’ were the predominant themes in the construction of journalistic narratives about these territories, which corresponds to over 70% of the topics” covered during this period on favelas.

International outlets tend to echo some of the biases and negative perceptions of favelas apparent in Brazilian mass media. In Catalytic Communities’ 2009-2014 Favelas in the Media report, the following trend emerged across six major English-language media groups:

“Clearly negative articles significantly outweigh clearly positive ones in every year, and the most common attributes are consistently negative, across all six outlets: favelas are portrayed as ‘sites of violence’ and ‘sites of drug/gang activity’ while residents are portrayed as ‘financially poor.’ These patterns reinforce the misconception that the only newsworthy topics about favelas are negative.”

Moreover, in examining representations of favelas over the past 30 to 35 years, the Observatório de Favelas study concluded that Brazilian mainstream media works to “establish direct associations between these territories and the phenomenon of violence in the large centers… such that society naturalizes violence against residents of favelas, blaming residents themselves when they are victims—not the authors—of violence.”

Often lacking solid evidence, black youth from favelas suspected of crimes are typically characterized by mainstream media as “drug traffickers,” “criminals,” and “thieves.” On the other hand, a racial double standard is applied: white suspects are frequently described as “middle class youths,” “teenagers,” “students” or “young residents” of the South Zone who made a “wrong choice,” “took justice into their own hands” or “challenged the law.”

Violence is simultaneously sensationalized—blurring the lines between fiction and reality—and normalized, creating the illusion that favelas are inherently dangerous urban spaces inhabited by criminally-prone individuals. In depicting violence as a “spectacle” but also as a normal aspect of life in favelas, these media representations ignore systemic and structural conditions underlying violence and criminality not just in favelas—but in the city as a whole and within society at large.

Need for Reform

The criminalization of poverty remains deeply rooted in the fabric of society in Rio de Janeiro. As the city’s most marginalized residents seek to break the cycle of poverty, their opportunities to overcome it are fundamentally threatened by their association to criminality in the eyes of the government, police force, wealthy media interests, and many upper or middle-class Brazilians. Reform of discriminatory laws, militarized police practices and the unjust penal system are all necessary to combat this cycle, but they must also be accompanied by sustained and effective policies to reduce structural inequality through education, health care and economic opportunity.