“You aren’t from the favela. You’re from the world,” Iara Oliveira, founder of the Alfazendo NGO, tells her students. Alfazendo is an educational NGO based in the City of God favela in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone. Frustrated over the state of education in her community, Oliveira and a small group of City of God residents founded Alfazendo in 1998 to improve literacy and tutor students for the college entrance exam. “We were young people that wanted other solutions,” she says. Efforts like Alfazendo’s represent an important element of the education system in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Literacy and attendance rates have risen in the past few years, in part thanks to communities creating solutions to address persisting problems and gaps.

A lack of schools makes attendance challenging in some favelas. Rio das Pedras is the third largest single favela in Rio with a population of over 50,000. Yet the community has only two public elementary schools to serve the students there. In 2016, completing school through the high school level became obligatory by law, but some favelas don’t have high schools in the community. Students must travel elsewhere to complete their high school education. Rio das Pedras has one public high school; Maré in the North Zone has none. City of God had a similar lack of high schools until recently. “We spent 40 years fighting to get a high school inside City of God. We got the school. We got a place for the school. We got the government to start the work,” said Oliveira. However, the work is no longer in progress due to the current political situation in Brazil, according to Oliveira.

Oliveira expresses concerns that in the favela’s school the curriculum is outdated and not engaging and that teaching methods haven’t evolved. According to Oliveira, teaching methods have remained the same since she was a child and are very “traditional.”

Another concern is teacher quality, especially in regards to preparation. “They aren’t prepared to face the reality,” says Oliveira. Another problem is that teaching in a school may be the first time that a teacher enters a favela. “You have teachers who are from the community that are more engaged–they fight more [on behalf of students]. We have teachers in these schools that are from outside. They come only to give the class and leave,” says Oliveira. “They come only because it’s a public post.”

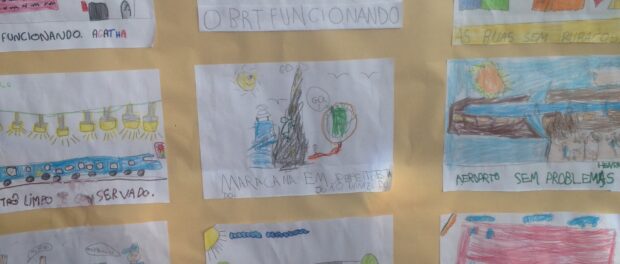

Alfazendo seeks to offer solutions to some of these challenges. In addition to the original tutoring and literacy services, it also provides 50-minute “socio-environmental” courses through its Eco Network program. Eco Network reaches 7,000 students in 28 schools and educational institutions. It has a branch in the North Zone’s Maré favela administered through CEASM (Maré Center of Solidarity Studies and Actions). Older students in the community act as “agents” and work with Eco Network’s staff to provide classes.

Fernanda Müller and Lucas de Sousa both grew up in City of God and are co-coordinators of the Eco Network project. While Eco Network explores one thematic unit per academic year, they field questions from students as they arise. Such topics can include sexuality, crime, violence, and family matters. “It’s spontaneous,” says de Sousa.

Special needs present a significant challenge and gap in the education system in favelas. In Rio das Pedras, students with special needs engage with the community in Jacarepaguá where they receive physical therapy and counseling. The Claudio Besserman Vianna Bussunda school in Rio das Pedras has 50 students with special needs and only two aides. A lack of psychologists and paraprofessionals on the school staff means that special needs students attend classes without any specialized support, an added challenge for teachers who may not feel prepared to work with them.

“They don’t educate teachers to be able to work with a child the way they arrive,” says Oliveira. A small number of schools specialize in students with special needs, but cuts to education have made it harder for schools to work with those students. Oliveira explains, “The City should have specialists inside the school. Before you had an interdisciplinary body in the school. You had the social worker, the educational psychologist, psychologist, and teachers. Now you don’t anymore. Now you just have teachers.”

But it’s not just professional staff that’s missing from schools. Schools no longer have funding for the grounds staff that monitor the school and guard the entrance. “The government took the grounds staff. Now we don’t have a doorman,” says Maria Aparecida Rocha de Camargo, coordinator at the Claudio Besserman Vianna Bussunda school. This presents a safety issue, as students can leave the school without permission. In Rio das Pedras, community members are stepping up to fill in for the staff as volunteers but de Camargo worries what would happen in an emergency situation.

Another time community members stepped in to solve the school’s resource problem by donating toilet paper. The lack of material resources and funding is hard for educational professionals to accept in the face of massive investments in mega-events, like the Olympics, even after Rio de Janeiro’s state government declared a “state of calamity” in June.

All favelas are not the same, especially in terms of security and violence, which can affect education. City of God has a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP), as does Rocinha, a favela in Rio’s South Zone and also the largest favela in the city. Despite the UPP, violence continues to be an issue in the community. In City of God, it is not unusual for schools to close because of conflict.

The NGO Rocinha Mundo da Arte provides a space for children to go after school to play, draw, do activities—to be safe. Every weekday from 2pm to 6 pm the door to Mundo da Arte is open for any child to come and go, meaning students who attend morning or after school sessions are able to participate. “My father started the organization to take kids off of the street,” says Iris Santos who now coordinates Mundo da Arte. She says the hope of the organization is to “take kids off the street so they have a place to learn and play safely.” The organization accepts any school-age student who is interested in art. Art, according to the group, is a tool to “show other social and intellectual possibilities.”

Mundo da Arte also provides extra tutoring for students who struggle with learning. Santos says that teachers can be unmotivated and need to be “trained more” to teach students better. She blames a lack of funds in public schools for these problems. “I’d like for schools to invest more in libraries, sports, and healthy food for the students,” she says. She explains that the children are what sustains her in her job, despite the hour-and-a-half commute she experiences daily after moving to Jacarepaguá. “My dedication is to the children, [so] that they have more creativity and curiosity to learn,” she says.

The community efforts to solve the problems that persist in the education system are many. However, even if a student does manage to overcome the challenges, the result can in turn become a problem for the community when brain drain occurs. “You have a lot of movement out [of the community]. You have migration,” according to Oliveira. She described students as thinking, “I’m going to graduate and I’m leaving… I’m going to find a job and I’m going to leave here.”

Alfazendo hopes to combat that thought process by motivating students to stay in the community and contribute to City of God’s development. Oliveira says, “I would say that I want the children of City of God–or anywhere–to have the same opportunities that I had–I have a network of friends and people that helped me get to where I am.”

Common misperceptions and stigma around favelas usually focus on drug trafficking, crime, and violence, rather than the historic neglect and exclusion by the government. Education represents an important area where favelas are combating that neglect by creating their own solutions and working to improve their communities.

Contributions to Alfazendo and Eco Rede can be made by emailing ecorede@yahoo.com.br.

Contributions to Rocinha Mundo da Arte can be made by contacting Iris Santos at iris07_santos@icloud.com.

Raven Hayes is a graduate student in the Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research focuses on educational development and the intersection of schools, poverty, and community.